US Pharm.

2007;32(10)(Diabetes suppl):3-8.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) currently

affects an estimated 20.8 million people within the United States, with a

current worldwide prevalence estimated at 180 million and which is expected to

double by 2030.1,2 Despite the many advances in the management of

both type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in

recent years, the average glycated hemo globin test (HbA1c) result of

patients with diabetes increased from 7.7% to 7.9% between 1990 and 1999.3

Strong evidence exists demonstrating the benefits of tight glycemic control

in T1DM and T2DM patients; however, glycemic goals are not adequately achieved

for many patients.4-6 While people with T1DM require insulin, many

T2DM patients could improve their glycemic control by the initiation of

insulin therapy, but they are either not prescribed insulin or have fear

associated with the injection process.6

The advent of dry powdered

insulin delivered by pulmonary inhalation provides an alternative mode of

delivery for patients with perceived barriers to the use of insulin. One

clinical trial looked at the acceptance of insulin therapy in 700 participants

with T2DM and an HbA1c result greater than 8%. The subjects in this study were

randomized to receive information regarding the risks and benefits of various

treatment options.7 A treatment regimen that included insulin was

opted for by 43.2% of patients in the group that had received information on

inhaled, dry powder insulin (IDPI), compared with 15.5% of those offered

information only on subcutaneous (SC)insulin therapy. Results from this trial

suggest that availability of inhaled insulin may increase acceptance of

insulin therapy in patients not currently using insulin. This review will

discuss the clinical pharmacology, tolerability, contraindications and

precautions, side effects, and special considerations of the currently

marketed IDPI product Exubera.

IDPI Comparative Efficacy

Five phase II or III efficacy trials were conducted comparing HbA1c reduction

in participants receiving bolus premeal inhaled insulin (Exubera) plus insulin

isophane suspension (NPH), Ultralente, or insulin glargine for their basal

insulin needs versus patients receiving bolus regular SC insulin plus NPH,

Ultralente, or insulin glargine basal insulin. These trials enrolled a

combined total of 1,354 participants with T1DM.8-12 In these

studies, IDPI and SC regular insulin achieved similar HbA1c reductions and

percentage of patients achieving an HbA1c less than 7%. Additionally, eight

comparative efficacy studies enrolled a total of 2,398 T2DM patients

uncontrolled with diet and exercise, sulfonylurea monotherapy, metformin

monotherapy, metformin plus a sulfonylurea, or an insulin secretagogue plus an

insulin sensitizer and were randomized to receive either IDPI monotherapy or

the addition of IDPI to their current regimen.13-20 Results from

these trials demonstrated that the addition of IDPI further reduced HbA1c

levels and allowed more patients to achieve an HbA1c less than 7%. In both

T1DM and T2DM, clinical trials show IDPI to have similar efficacy when

compared to SC regular insulin, and in some instances superior efficacy, when

compared to oral antidiabetic therapies.

Adverse Events

While IDPI therapy carries with

it the same considerations and precautions as injectable insulin preparations

(e.g., risk of hypoglycemia, weight gain), the delivery mechanism of IDPI

involves a variety of additional factors for consideration by prescribers and

pharmacists alike. A major consideration for determining the appropriateness

and safety of inhaled insulin use in a given patient is assessment of

pulmonary function. Patients with lung disease (e.g., asthma, chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], etc.) have potentially impaired

inspiratory capabilities that may impede adequate delivery of insulin to the

lung for absorption. Due to this possibility, the manufacturer recommends that

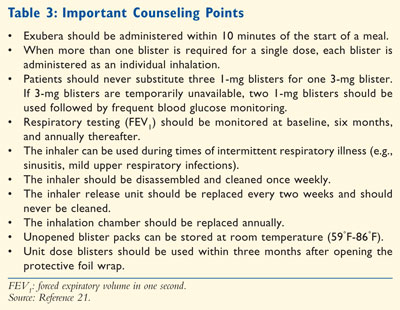

all patients undergo spirometry testing (forced expiratory volume in one

second [FEV1]) prior to the initiation of IDPI therapy.

Additionally, FEV1 monitoring should be conducted six months after

the initiation of IDPI therapy and every year thereafter to ensure that FEV

1 changes have not occurred as a consequence of IDPI use. Likewise,

respiratory adverse events (e.g., cough, dyspnea) should be monitored closely

as with any inhaled medication.21

Cough,

dyspnea, increased sputum, and epistaxis were the most frequently reported

adverse respiratory events during clinical trials involving both T1DM and T2DM

patients.21 The single most common respiratory adverse event during

clinical trials was cough.8,13,16,18,19,22 Cough occurred in

approximately 30% of patients with T1DM and in approximately 22% of subjects

with T2DM during clinical trials.21 Mild-to-moderate nonproductive

cough was most commonly observed. Cough frequently decreased over time,

indicating that this adverse reaction often resolves or lessens with continued

treatment, with a two-week median duration of increased cough in one study.

8,13,16,18,19,22 Another study reported a decrease in the incidence and

prevalence of cough with continued treatment when the initial four weeks of

treatment were compared directly to the incidence of cough witnessed during

weeks 20 through 24.22

Dyspnea was reported with a frequency of 4.4% [0.9% for SC insulin comparator]

and 3.6% (2.5% and 1.4% for SC insulin and oral agent comparators,

respectively) in IDPI-treated patients with T1DM and T2DM, respectively.21

Additionally, increased sputum production was noted in 3.9% of IDPI-treated

patients with T1DM, compared to an incidence of 1.3% for the SC insulin

comparator. In patients with T2DM treated with IDPI, 2.8% reported increased

sputum, compared to 1.0% and 0.5% for the SC insulin and oral agent comparator

groups, respectively.21 The incidence of epistaxis was also

increased in patients receiving IDPI, with 1.3% incidence (0.4% for SC insulin

comparator) for subjects with T1DM and 1.2% (0.4% and 0.8% for SC insulin and

oral agent comparators, respectively) for patients with T2DM.21

As with the use of any pulmonary medication, adverse respiratory events

related to pulmonary function is of clinical importance. Pulmonary function

parameters were closely monitored during clinical trials to asses the safety

of IDPI. Results from 12-week and 24-week

trials showed small,

comparable mean declines between inhaled insulin–treated subjects and

comparator groups for a variety of respiratory parameters, including but not

limited to FEV1.8,10,13,16,18,20,22 It is important to

note, however, that respiratory changes generally resolved following drug

discontinuation. Further pulmonary data taken from 580 patients with T1DM and

620 patients with T2DM treated with IDPI or SC insulin are reported by the

manufacturer in the IDPI package insert. 21 After two years of

therapy, the mean difference in FEV1 between the IDPI and

comparator group was -0.04 L. Patients with lung function below 70% of

predicted FEV1 prior to initiation should not receive IDPI, and any

patient experiencing a decline of lung function of 20% or more from baseline

while using IDPI should discontinue use of the product.

Contraindications and Precautions

Because IDPI presents a novel delivery mode in comparison to other currently

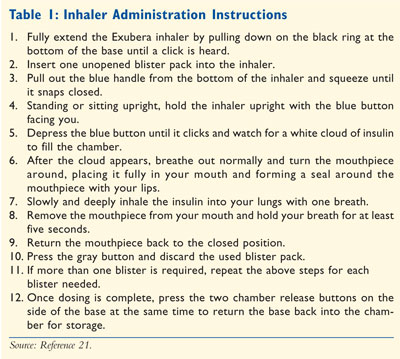

marketed insulin products (TABLE 1), its prudent use requires

additional and unique considerations for both health care providers and

consumers. Current smokers or those who have quit smoking for less than six

months should not receive IDPI. Similarly, if a patient begins or resumes

smoking while taking IDPI, this treatment should be discontinued immediately.

Patients with asthma, COPD, or other lung diseases should not use IDPI. IDPI

can be used during mild, intercurrent respiratory illnesses such as rhinitis,

upper respiratory infection, and bronchitis; however, more vigilant monitoring

of blood glucose should be practiced until the illness resolves and blood

glucose levels have normalized.21,23 The use of IDPI has been

studied in clinical trials for the treatment of both T1DM and T2DM. When

treating T1DM patients with IDPI, it is important that patients also receive a

long-acting insulin for their basal insulin needs. For patients with T2DM,

however, IDPI can be utilized in conjunction with lifestyle modifications

(i.e., diet and exercise), basal insulin, or oral diabetes therapies.

Dosing and Administration

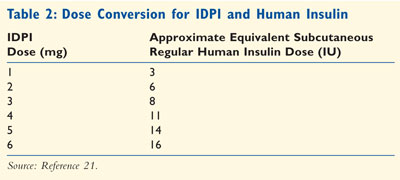

IDPI blisters come in 1-mg (equal to 3 units of regular insulin) and 3-mg

(equal to 8 units of regular nsulin) strengths. TABLE 2 outlines

approximate dose equivalencies between regular SC insulin and IDPI. It is

important to note that three 1-mg blisters are therefore not equivalent to one

3-mg blister. For those patients initiated on IDPI therapy, without any

previous insulin use from which to base dosing parameters, a patient's initial

dose is calculated based on weight and rounded to the nearest milligram value

using the following formula provided by the manufacturer: body weight (kg) x

0.05 mg/kg = premeal dose (mg). Following the initiation of IDPI therapy, the

dose is titrated corresponding to clinical effectiveness and specific patient

needs, as with any insulin product.21 Once a target dose is

identified, patients should combine 1-mg and 3-mg blisters to achieve their

target dose so that the least amount of blisters are used. If a patient is

stabilized on a dosage regimen utilizing 3-mg blisters but 3-mg blisters are

temporarily unavailable, two 1-mg blisters can be substituted for one 3-mg

blister until 3-mg blisters are again available. If such a temporary

substitution is made, patients should be instructed to monitor blood glucose

concentrations closely.21

IDPI use is associated with a faster onset of action compared to traditional

SC regular human insulin, requiring that it be dosed no more than 10 minutes

prior to meals.21 The duration of action of IDPI, however, is

approximately equal to that of SC regular insulin. Because IDPI is a

fast-acting insulin, the manufacturer recommends that IDPI be used in

combination with a long-acting insulin preparation in those with T1DM, and

either as monotherapy or in combination with oral medications or long-acting

insulin in patients with T2DM.21

IDPI blisters should be used only in conjunction with the inhaler. A fully

assembled inhalation device consists of the inhaler base, an inhalation

chamber, and an IDPI release unit as illustrated in FIGURE 1.

Maintenance of the IDPI inhalation device should include regular cleaning

weekly. The inhalation chamber should be cleaned with soap and water, while

the inhaler unit should be wiped down with a wet cloth, avoiding the release

unit and blister insertion point. The release unit should never be cleaned and

should instead be replaced every two weeks. Likewise, the entire inhaler

should be replaced annually.21 Unopened inhaler blister packs

should be stored at controlled room temperature (59°F-86°F). Once opened, dose

blisters should be protected from moisture and stored under the protective

foil overwrap. Also, once the foil wrap is opened, blisters should be used

within three months (TABLE 3).21

Conclusions

Exubera is the first dry powder, inhaled insulin available for the treatment

of DM, and with the introduction of IDPI comes a hopeful future for future

advancements in pulmonary insulin delivery. The inhaler can be used in T1DM

patients in combination with basal insulin, and in T2DM patients in

combination with basal insulin and/or oral therapies. The inhaler does have

its limitations. The dosing can prove difficult for some patients because the

use of multiple blisters requires multiple inhalations. Additionally, dosing

can become confusing for some patients considering one 3-mg blister is not

therapeutically equivalent to three 1-mg blisters. Despite these potential

limitations, this novel delivery of rapid-acting regular insulin to the

respiratory tract has the potential to revolutionize the treatment of diabetes

by providing a more readily acceptable administration of insulin to patients

who could benefit from insulin therapy, especially for those unable or

unwilling to undergo frequent insulin injections.

REFERENCES

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Fact Sheet: General Information and National Estimates on Diabetes in the United States, 2005. Atlanta, GA: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2005.

2. World Health Organization: Diabetes: What is Diabetes? Available at: http:www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/ fs312/en/. Accessed July 25, 2007.

3. Koro CE, Bowlin SJ, Bourgeois N, et al. Glycemic control from 1988 to 2000 among U.S. Adults diagnosed with type 2 diabetes: a preliminary report. Diabetes Care.2004;27:17-20.

4. Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:977-986.

5. UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulfonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complication in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet. 1998;352:837-853.

6. Cefalu WT. Evaluation of alternative strategies for optimizing glycemia; progress to date. Am J Med . 2002;113(6A):

23S-35S.

7. Freemantle N, Blonde L, Duhot D, et al. Availability of inhaled insulin promotes greater perceived acceptance of insulin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:427-428.

8. Quattrin T, Belanger A, Bohannon NJV, et al., for the Exubera Phase III Study Group. Efficacy and safety of inhaled insulin (Exubera) compared to subcutaneous insulin therapy in patients with type 1 diabetes: results of a 6-month, randomized, comparative trial. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2622-2627.

9. Skyler JS, Cefalu WT, Kourides IA, et al. Efficacy of inhaled human insulin in type 1 diabetes mellitus: a randomised proof-of-concept study. Lancet.2001;357:331-335.

10. Skyler JS, Weinstock RS, Raskin P, et al., for the Inhaled Insulin Phase III Type 1 Diabetes Study Group. Use of inhaled insulin in a basal/bolus insulin regimen in type 1 diabetic subjects: A 6-month, randomized, comparative trial.

Diabetes Care . 2005;28:1630-1635.

11. Norwood P, Dumas R, Cefalu W, et al. Randomized study to characterize glycemic control and short-term pulmonary function in patients with type 1 diabetes receiving inhaled human insulin (Exubera). J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(S6):2211-2214.

12. Skyler JS, Jovanovic L, Klioze S, et al., for the Inhaled Human Insulin Type 1 Diabetes Study Group. Two year safety and efficacy of inhaled human insulin (Exubera) in adult patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:579-585.

13. DeFronzo RA, Bergenstal RM, Cefalu WT, et al. Efficacy of inhaled insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes not controlled with diet and exercise: a 12-week, randomized, comparative trial. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1922-1928.

14. Weiss SR, Cheng SL, Kourides IA, et al. Inhaled insulin provides improved glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus inadequately controlled with oral agents: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med.2003;163:2277-2282.

15. Simonson DC, Turner RR, Hayes JF, et al. Improving quality of life in type 2 diabetes when Exubera is added after failure on metformin: a multicenter, international trial [abstract]. Diabetologia. 2004;47(suppl 1):A311.

16. Barnett AH, Dreyer M, Lange P, Serdarevic-Pehar M. An open-randomized, parallel-group study to compare the efficacy and safety profile inhaled human insulin (Exubera) with metformin as adjunctive therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes poorly controlled on a sulfonylurea. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1282-1287.

17. Rosenstock J, Zinman B, Murphy LJ, et al. Inhaled insulin improves glycemic control when substituted for or added to oral combination therapy in type 2 diabetes: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:549-558.

18. Hollander PA, Blonde L, Rowe R, et al. Efficacy and safety of inhaled insulin (Exubera) compared with subcutaneous insulin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes: results of a 6-month, randomized, comparative trial. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2356-2362.

19. Cefalu WT, Skyler JS, Kourides IA, et al., for the Inhaled Insulin Study Group. Inhaled human insulin treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:203-207.

20. Rosenstock J, Foyt H, Klioze S, et al. Inhaled human insulin (Exubera®) therapy shows sustained efficacy and is well tolerated over a 2-year period in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2DM) [abstract]. Diabetes. 2006;55(suppl):abstract 109-OR.

21. Exubera [US package insert]. Pfizer Inc. Exubera (insulin human [rDNA origin]) inhalation powder: New York, NY: Pfizer Labs; 2007.

22. Skyler JS, Weinstock RS, Raskin P, et al. Use of inhaled insulin in a basal-bolus insulin regimen in type 1 diabetic subjects. Diabetes Care. 2004;28:1630-1635.

23. Setter SM, Levien TL, Iltz JL,

et al. Inhaled dry powder insulin for the treatment of diabetes mellitus.

Clin Ther. 2007;29:795-813.

To comment on this article, contact editor@uspharmacist.com.