US Pharm. 2008;33(12):HS19-HS27.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the percentage of overweight or obese persons in the U.S. population almost doubled between the years 1976-1980 and 2003-2004.1 Obesity is a chronic disease characterized by excessive body fat. Obesity comes from the Latin word obesus, meaning "fattened by eating."2 Genes, medical conditions (e.g., Cushing's disease, hypothyroidism), medications leading to weight gain and/or appetite stimulation, and energy imbalance (total calories consumed exceeding total calories burned per day) are some of the risk factors that make individuals prone to obesity.2

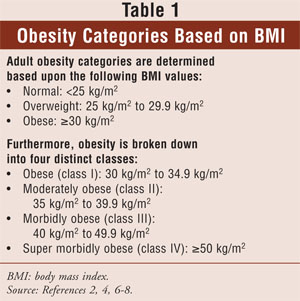

Obesity affects every generation and every gender. Presently, there are over 60 million obese people (based on body mass index [BMI] calculations) in the United States, and approximately 4.8% of those 60 million are morbidly obese.3-5 BMI is calculated using the following formula: BMI = weight (kg)/height (m)2. Weight and obesity categories based on BMI are described in TABLE 1.2,4,6-8

Obesity and Its Complications

Obesity leads to morbidity and medical complications. Examples of diseases and complications related to obesity include cardiovascular, immunologic, endocrine, neurologic, psychological, gastrointestinal (GI), genitourinary, musculoskeletal, respiratory, bone, and joint disorders, and various cancers.2,9 The pharmacist plays an important role in a treatment and weight loss program for obese patients, specifically in the medication management component.

The American College of Physicians has published recommendations on pharmacologic and surgical management for obese patients. The recommendation for obese patients with BMI >=30 kg/m2 is to start losing weight by changes in diet, exercise routine, and lifestyle. If changes in diet and lifestyle do not bring expected results, medical therapy may be warranted. Surgical procedures should be offered to severely obese patients with BMI >=40 kg/m2 who have failed traditional nonsurgical approaches.10,11

The 1991 National Institutes of Health Consensus identified patients with BMI >40 kg/m2 and BMI between 35 kg/m2 and 40 kg/m2 with obesity-related comorbidities as good candidates for bariatric surgical procedures.12 Patients with untreated major depression or psychosis, binge-eating disorders, and current drug and alcohol abuse would be excluded as potential candidates for bariatric surgery.7

Types of Bariatric Surgery

The field of bariatric surgical procedures consists of three major approaches. The first surgical approach--restrictive--is aimed at decreasing the patient's caloric intake. Vertical banded gastroplasty and laparoscopic adjustable gastric band procedures are examples. These procedures only restrict stomach size.7,11

The second approach--malabsorptive--is aimed at decreasing the absorption of nutrients. Jejunoileal bypass, which is rarely used today, and biliopancreatic diversion, with or without duodenal switch procedures, belong to the malabsorptive category.7,11

Finally, more complicated surgeries combine both restrictive and malabsorptive principles and fall under the third category--combination surgery. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, or simply gastric bypass, is a procedure that combines principles of malabsorptive and restrictive approaches. It is the most common type of combination bariatric surgery performed in the U.S.7,11

From 1993 to 2004, the number of completed bariatric surgeries in the U.S. increased approximately 10-fold, with 218,000 cases projected in the year 2010.13,14

Pharmacist's Role in Preop

The operating room (OR) pharmacist's duty begins the moment a patient is admitted into the hospital for bariatric surgery. First and foremost, the pharmacist should identify the patient as type normal, overweight, obese, moderately obese, morbidly obese, or super morbidly obese, based on the patient's BMI value (TABLE 1). Once that is established, the pharmacist would advise physicians on appropriate medication doses, which should be based on either actual body weight, adjusted body weight, or ideal body weight. Additionally, the pharmacist should educate the patient on the effects of smoking cessation.15 Furthermore, the pharmacist should be aware of the possible physiologic changes this population may experience, such as increase in fat tissue; increase in cardiac output; increased levels of serum lipoproteins, triglycerides, free fatty acids, and cholesterol; increase in alpha-1 acid glycoprotein; changes in liver and kidney functions; and desensitization of acetylcholine receptors, which may lead to alterations in some drugs' tissue and plasma binding and distribution, hepatic and renal clearance, and efficacy.16-20

These physiologic changes may have an effect on pharmacokinetics and the pharmacodynamic performance of some medications. For example, in vitro studies showed deescalation in protein binding for antibiotics such as dicloxacillin, cefamandole, and sulfamethoxazole, and escalation in protein binding of other medications such as benzylpenicillin and cefoxitin, in the presence of high levels of free fatty acids.18 Another example is alpha-1 acid binding glycoprotein, one of the major plasma proteins. It binds most of the basic drugs like clindamycin, an antibiotic, and propranolol, a beta-blocker. Studies have shown that as the level of alpha-1 acid glycoprotein was increasing, the unbound portion of propranolol was decreasing.18,21

Yet another aspect of the pharmacist's role in the OR is assisting the surgical team in the development of preoperative (preop) protocol for a patient undergoing bariatric surgery. Generally, before the surgery is performed, the patient undergoes preop antibiotic prophylaxis and an antithrombotic prophylaxis regiment to prevent the formation of thrombosis (i.e., deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism). In some cases, a patient may require medical prophylaxis against acid aspiration. Medications such as H2-blockers, metoclopromide, proton pump inhibitors, and sodium citrate should be recommended.1,22,23 Furthermore, the OR pharmacist should closely monitor the patient's glucose level.24 Moreover, the OR pharmacist should advise physicians and nurses about unpredictable and unreliable absorption of medications administered via IM and SC routes, due to the patient's excessive fatty tissue mass.1,22 Lastly, it might be beneficial to screen patients for Helicobacter pylori and, if detected, treat it prior to surgery. If left untreated, H. pylori may increase the risk for postoperative (postop) ulcer formation.22

Pharmacist's Role in Postop

The OR pharmacist continues to be an important figure in the patient's therapy even after the operation. Postop medication management is as important to the success of the program as preop medication management. After the surgery, the OR pharmacist will know which type of bariatric surgery--restrictive, malabsorptive, or combined--the patient has undergone. Based on the type of surgery, the pharmacist will recommend the best agent for the medical therapy. In all cases, a pharmacist should advise physicians to switch all medications to liquid formulations or capsule formulations that can be opened. Another alternative is immediate-release tablet formulations that can be crushed. These medications should be administered for one day to two weeks. In some cases, this requirement may last up to one month.12,25

Pharmacists and physicians expect to see positive results in postop patients. After three months, blood pressure, blood glucose levels, and acid reflux are expected to normalize. This trend, in turn, will decrease the number of medications and/or doses needed. This is especially beneficial when there is an existing "polypharmacy" treatment regime to control gastroesophageal reflux, cardiovascular conditions, and diabetes. On the other hand, postop complications may require additional medical treatment.12,26

The nature of the bariatric procedure requires some changes in the patient's medication management. Hospital pharmacy departments are well aware of such changes and will inform physicians and other health care providers about these issues. Depending on the type of bariatric procedure, the OR pharmacist may recommend supplements of electrolytes and vitamins to achieve the necessary vitamin and mineral balance for patients who are at risk for malabsorption. Physicians should be informed about alternatives to oral routes of medication administration, such as sublingual or rectal, and advise against using time-release formulations and medications falling under the category "Do Not Crush." The use of bisphosphonate derivatives and nonsteriodal anti-inflammatory drugs should be minimized or eliminated due to increased risk of GI ulceration. Finally, the OR pharmacist may recommend limiting medical products containing monosaccharides or disaccharides and mannitol to decrease the risk of dumping syndrome.27-29

Dumping syndrome is fast gastric emptying, which occurs right after a meal. It is characterized by symptoms of nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, dizziness, and fatigue and is predominately associated with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass but not laparoscopic banding.12

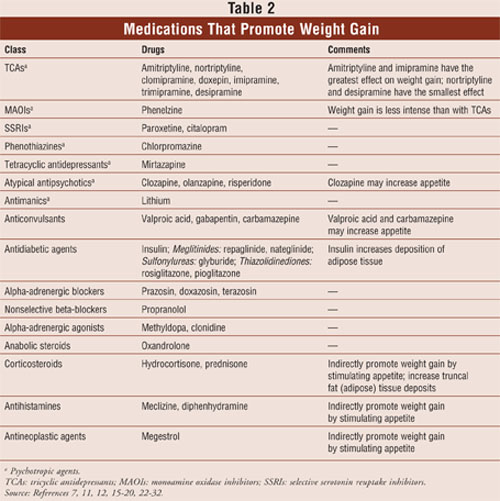

Another important part of postop pharmaceutical care is to identify and advise on medications contributing to weight gain and increase in appetite. The OR pharmacist should be able to identify such agents and make appropriate recommendations. This area is very important in postop care, simply because a patient would not be able to lose weight as expected due to the newly gained weight or increased appetite induced by the medications. TABLE 2 identifies medications causing weight gain and increases in appetite, broken down by categories based on therapeutic use.

Based on the earlier studies, two logical groupings of medical compounds have emerged: 1) medical compounds increasing weight, and 2) medical compounds stimulating appetite. Some of the psychotropic agents that have strong antimuscarinic side effects induce thirst. Tricyclic antidepressants, valproic acid, and citalopram increase carbohydrate craving.30,31 Lithium promotes weight gain by inducing thirst and increasing carbohydrate craving. Pharmacologically speaking, blockade of serotonin transmission, particularly 5HT2A and 5HT2C, and blockade of dopamine transmission, particularly D2, provoke patients to eat more.30,32 Interestingly enough, the weight gain related to psychotropic medical compounds and thiazolidinediones is primarily due to an increase in adipose tissue.30,33 Clozapine and olanzapine usage raises serum levels of leptin in patients taking these medications. Furthermore, carbamazepine and thiazolidinediones are well known to cause water retention and weight gain. Medical compound carbamazepine is associated with fat deposition and appetite stimulation.30-32 Nonselective beta-blockers and clonidine decrease the sympathetic nervous system, thus reducing metabolism.30

The second group of compounds promotes appetite. Medications expressing H1-receptor or postsynaptic serotonin receptor blocking effects or activation of GABA receptors induce appetite, ultimately causing a patient's weight to go up.33,34 Some antidiabetic medications cause hypoglycemia, which provokes appetite.

Being aware of the medications that can slow down the postop patient's progress in weight loss, the OR pharmacist should recommend the following30,32:

• Try to avoid medications causing weight gain or increasing appetite as the initial therapy.

• Weigh the ratio between risk and benefit.

• Minimize medication doses if the drugs cannot be avoided.

• Use alternative medications from the same therapeutic category, if possible, when 5% to 7% or more of weight increase from the baseline is observed, due to the increased risk of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer.

Summary

Without a doubt, patient education is the key to the success of a weight loss program. Patients will learn about appropriate levels of physical activity and the right diet. The combination of physical exercise and diet may be enough to produce desired results for many patients. However, in some cases, exercise and diet may be necessary but not sufficient elements for reaching desired weight loss goals. In that case, from the moment a bariatric patient walks into the hospital to the point of discharge, a team of health care professionals will work with the patient to achieve the ultimate goal of losing harmful extra pounds. The OR pharmacist is an essential figure in the bariatric treatment process. The pharmacist will work on each patient's medications, adjusting them personally to the needs of that patient, in order to ensure that medication errors do not stand in the patient's way to achieving a healthy weight.

REFERENCES

1. Overweight and Obesity. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/obesity/index.htm. Accessed March 3, 2008.

2. Adams JP, Murphy PG. Obesity in anaesthesia and intensive care. Br J Anaesth. 2000;85:91-108.

3. Markel TA, Mattar SG. Management of gastrointestinal disorders in the bariatric patient. Med Clin North Am. 2007;91:443-450.

4. Sanchez VM, Schenider BE, Mun EC. Complications of bariatric surgery. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com. Accessed February 23, 2008.

5. DeMaria EJ. Bariatric surgery for morbid obesity. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2176-2183.

6. Colquitt J, Clegg A, Loveman E, et al. Surgery for morbid obesity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(4):CD003641.

7. Mun EC, Tavakkolizaden A. Surgical management of severe obesity. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com. Accessed February 23, 2008.

8. Powers KA, Rehrig ST, Jones DB. Financial impact of obesity and bariatric surgery. Med Clin North Am. 2007;91:321-338.

9. Takahashi AM. Obesity and considerations in the bariatric surgery patient. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2007;24:191-222.

10. Snow V, Barry P, Fitterman N, et al. Pharmacologic and surgical management of obesity in primary care: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:525-531.

11. Elder KA, Wolfe BM. Bariatric surgery: a review of procedures and outcomes. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2253-2271.

12. Boan J, Mun EC. Management of patients after bariatric sugery. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com. Accessed February 23, 2008.

13. Virji A, Murr MM. Caring for patients after bariatric surgery. Am Fam Physician. 2006;73:1403-1408.

14. Santry HP, Gillen DL, Lauderdale DS. Trends in bariatric surgical procedures. JAMA. 2005;294:1909-1917.

15. Fernstrom JD, Choi SJ. The development of tolerance to drugs that suppress food intake. Pharmacol Ther. 2008;117:105-122.

16. Wurtz R, Itokazu G, Rodvold K. Antimicrobial dosing in obese patients. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:112-118.

17. Lee JB, Winstead PS, Cook AM. Pharmacokinetic alterations in obesity. Orthopedics. 2006;29:984-988.

18. Blouin RA, Warren GW. Pharmacokinetic considerations in obesity. J Pharm Sci. 1999;88:1-7.

19. Casati A, Putzu M. Anesthesia in the obese patient: pharmacokinetic considerations. J Clin Anesth. 2005;17:134-145.

20. Cheymol G. Effects of obesity on pharmacokinetics. Implications for drug therapy. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2000;39:215-231.

21. Benedek IH, Fiske WD III, Griffen WO, et al. Serum alpha-1 acid glycoprotein and the binding of drugs in obesity. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1983;16:751-754.

22. Takahashi AM. Obesity and considerations in the bariatric surgery patient. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2007;24:191-222.

23. Raeder J. Bariatric procedures as day/short stay surgery: is it possible and reasonable? Curr Opin Anesthesiol. 2007;20:508-512.

24. Joseph B, Genaw J, Carlin A, et al. Perioperative tight glycemic control: the challenge of bariatric surgery patients and the fear of hypoglycemic events. Permanente J. 2007;11:36-39.

25. Sardo P, Walker JH. Bariatric surgery: impact on medication management. Hosp Pharm. 2008;43:113-120.

26. Malone M, Alger-Mayer SA. Medication use patterns after gastric bypass surgery for weight management. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:637-642.

27. Miller AD, Smith KM. Medication and nutrient administration considerations after bariatric surgery. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63:1852-1857.

28. Whipple Guthrie E. Bariatric surgery. US Pharm. 2007;32(9):HS27-HS37.

29. Fussy SA. The skinny on gastric bypass. US Pharm. 2005;30(2):HS3-HS12.

30. Malone M. Medications associated with weight gain. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:2046-2055.

31. Pijl H, Meinders AE. Bodyweight change as an adverse effect of drug treatment. Drug Saf. 1996;14:329-342.

32. Harrison B. Nursing considerations in psychotropic medication-induced weight gain. Clin Nurse Spec. 2004;18:80-87.

33. Kalra SP, Ueno N, Kalra PS. Stimulation of appetite by ghrelin is regulated by leptin restraint: peripheral and central sites of action. J Nutr. 2005;135:1331-1335.

34. Kalra SP. Circumventing leptin resistance for weight control. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:4279-4281.

To comment on this article, contact

rdavidson@jobson.com