US Pharm.

2008;33(4)(Oncology suppl):31-35.

ABSTRACT:

Skin, the largest organ in the human body, has several functions, including

protection from mechanical, thermal, and environmental impact.1

There are two main layers to the skin: the epidermis (outer layer) and the

dermis (inner layer). The epidermis contains flat cells called squamous cells,

round cells called basal cells, and the pigment-producing cells, melanocytes.

The dermis contains hair follicles, glands, and blood and lymph vessels.2

Cancer of the skin usually develops in the visible epidermis layer, making

most skin cancers detectable in the early stages.1

Skin cancer accounts for

nearly half of all the cancers in the United States.1 The three

most common types of skin cancers, named after the skin type from which they

arise, are squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), basal cell carcinoma (BCC), and

melanoma. Basal cell carcinoma and SCC are nonmelanoma-type skin cancers.3

It is estimated that more than 50,000 new cases of melanoma and one million

cases of nonmelanoma skin cancers are reported in the U.S. annually.1,3

Basal Cell and Squamous

Cell Carcinoma

Basal cell

carcinoma is the most common cancer in the U.S. and Australia, and SCC is the

second most common skin cancer in these countries, but its incidence is rising.

4,5 Basal cell carcinoma is predominantly found in elderly Caucasian

males.6 It is not typically found in those with dark-skinned

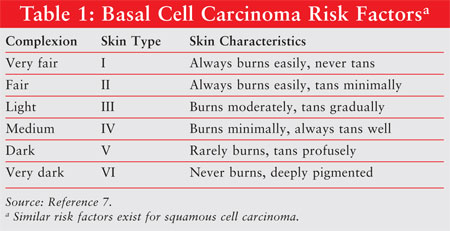

ethnicities.6 Risk factors for developing BCC include complexion

type [skin Type I (TABLE 1)], hair color (red or blond), eye color

(blue or green), the presence of freckles, and the incidence and severity of

sunburns or exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation in childhood. A family

history of skin cancer and use of immunosuppressive agents are also thought to

be contributory. Similar risks factors exist for SCC.7,8

Basal cell carcinoma generally has a

low incidence of metastasis, but can be locally invasive.4 In some

cases, it can result in disfigurement and require significant reconstructive

surgery.8 Eighty percent of cases involve the head and neck; the

remaining 20% of cases involve the trunk and lower limbs.6 This

malignancy is typically slow growing.4 A diagnosis of BCC may lead

to an increased risk for recurrent BCC, malignant melanomas, SCC, and/or other

noncutaneous malignancies.4,6 The prognosis of BCC is based upon

the size, site, margination, and histological differentiation of the tumor, as

well as host immunosuppression and effectiveness of previous treatment

modalities.4 Conversely, SCC is more likely than BCC to

metastasize, doing so in 3% to 4% of the cases.8 The site,

diameter, and depth of the tumor, as well as histological differences, host

immunity, and previous treatments dictate the metastatic potential of SCC.

5 Sun-exposed sites, excluding the lip and ear, have less metastatic

potential than areas with radiation or thermal injury, chronic draining

sinuses, chronic ulcers, and chronic inflammation.5

Patients and providers are

responsible for routine examination of the skin. The arms, face, and upper

chest are of particular interest.8 Patients will commonly present

to a clinic or their primary care provider with complaints of skin lesions

that have changed relative to their original size and color. In addition,

patients may experience and report some discomfort, bleeding, or healing

difficulties.8 Classic BCC can be waxy, translucent, or pearly in

appearance.8 Squamous cell carcinoma typically presents as an

indurated nodular tumor with or without keratinization.5

Biopsy confirmation is

strongly encouraged and recommended.4,5,8 Surgical excision remains

the gold standard so margins can be examined histologically to check for tumor

clearance. Other BCC treatment options include curettage and cautery surgery,

cryosurgery with liquid nitrogen, Mohs' micrographic surgery, radiotherapy,

and photodynamic therapy.6,8 Topical pharmacologic agents include

5-fluorouracil and imiquimod (Aldara).4,6,8 Both can be used for

early, superficial, or diffuse but mild disease.4,6,9 Topical

agents are not indicated in the treatment of SCC.5

Fluorouracil 5% topical cream

(Efudex), an antineoplastic antimetabolite, contains fluorinated pyrimidine

5-fluorouracil. It is an available treatment option for superficial BCC when

multiple lesions are present or if the location of the lesion makes

conventional treatment methods impractical.4,6,9 It is applied

twice daily to the lesion, initiating an inflammatory response consisting of

erythema, vesiculation, desquamation, erosion, and re-epithelialization.

8,10 Length of therapy is minimally three to six weeks but may be as

long as 10 to 12 weeks.

Adverse drug reactions

commonly associated with fluorouracil 5% topical cream are cutaneous in nature

and are generally related to the drug's pharmacological activity.10

The most frequent adverse reactions include application site reactions such as

burning, crusting, allergic contact dermatitis, erosions, erythema,

hyperpigmentation, irritation, pain, photosensitivity, pruritus, scarring,

rash, soreness, and ulceration. Patients should be counseled to avoid sun

exposure and occlusive dressings, which may intensify the reaction. Patients

should also be instructed to wash their hands immediately if 5-fluorouracil is

applied without gloves.10 Fluorouracil 5% topical cream is

contraindicated in women who are or who may become pregnant during therapy and

is classified as Pregnancy Category X.10 Fluorouracil 5%

topical cream is also contraindicated in patients with dihydropyrimidine

dehydrogenase (DPD) enzyme deficiency as fluorouracil is metabolized by the

DPD enzyme, potentially resulting in dose-limiting toxicity.† Additionally,

fluorouracil 5% is contraindicated in patients with known hypersensitivity to

any of its components.10

Imiquimod is a topical immune

response modifier. It is indicated in the treatment of biopsy-confirmed,

primary superficial BCC in immunocompetent adults with a maximum tumor

diameter of 2 cm located on the trunk, neck, or extremities, excluding the

hands and feet.6,9 It is used only when surgical methods are

medically less appropriate and patient follow-up can be reasonably assured.

The mechanism of action in the treatment of BCC is unknown. Imiquimod is

applied five times per week, prior to normal sleeping hours, and should be

left on the skin for approximately eight hours. The usual treatment course is

six weeks. The treatment area should include a 1-cm margin of skin around the

tumor. Before applying the cream, the patient should wash the treatment area

with mild soap and water and allow the area to dry thoroughly.

Most common adverse effects

are application-site reactions such as dryness, erythema, pruritus,

ulceration, scabbing/crusting, edema, erosion, and rash. Some of these local

reactions may require cessation of treatment. Treatment can be restarted once

intensity of the reaction lessens.11 Similar patient instructions

as noted with 5-fluorouracil should be provided.11 Imiquimod should

only be used during pregnancy if the potential benefits outweigh the potential

risks to the fetus. It is classified as Pregnancy Category C.11

As with fluorouracil 5% topical cream, imiquimod is contraindicated in

patients with known hypersensitivity to any of its components.11

Melanoma

Melanoma is the

most serious form of skin cancer. It is a malignant tumor that originates in

melanocytes, the cells that produce the pigment melanin that colors skin,

hair, and eyes. It is one of the fastest-growing cancers in the U.S.,

accounting for approximately 4% of all skin cancers and 75% of skin cancer

deaths. However, the prognosis is usually very promising if melanoma is

detected and treated early.12

Melanoma occurs more commonly

on the head, neck, or trunk in men and on the extremities in women, but it can

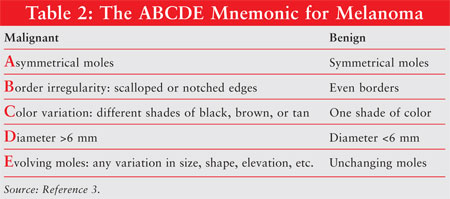

develop on any skin surface.13 One of the simplest tools available

for the early detection of malignant melanoma is the ABCDE mnemonic developed

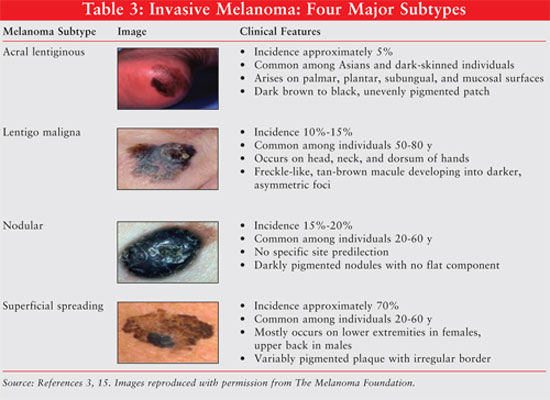

by the American Cancer Society (TABLE 2).3 The four major

subtypes of invasive melanoma in ascending order of frequency are acral

lentiginous, lentigo maligna, nodular, and superficial spreading melanoma (

TABLE 3). When melanoma is suspected, the diagnosis should be confirmed

with a skin biopsy. Once the diagnosis of malignant melanoma is confirmed, it

can be staged using the American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM (tumor, node,

and metastasis) system. Tumor thickness, ulceration, and nodal involvement

should all be considered in determining disease prognosis.14 In

addition, a comprehensive history, physical exam, pertinent laboratory panels,

and radiographs are also indicated to assess disease severity.15

Treatment of melanoma is based on

several factors, such as age and general health of the individual and disease

stage. For early-stage melanomas, total excision of the lesion while it is

minimally invasive or in situ is the key to reducing mortality.3

In advanced stages of melanoma, patients may require adjuvant therapy, such

as immunotherapy, chemotherapy, and radiation, along with surgery.16

As mentioned previously,

primary surgical excision is the treatment of choice for lesions that are

in situ. In these cases, a margin of 0.5 cm of normal skin around the

lesion is recommended.3 In the case of thin melanomas (<1 mm), a

margin of 1 cm is usually recommended, while a 2-cm margin is recommended for

intermediate-thickness melanoma (1-4 mm).14 Advantages of this

procedure include high cure rate and ease of administration. Mohs'

micrographic surgery can be considered for recurrent skin cancers and tumors

located in sensitive areas, such as face, genitals, fingers, and toes, where

it is important to preserve healthy tissue for functional and cosmetic

purposes.17

The five-year survival rate is

33% in patients with satellite lesions and metastasis to regional nodes.

Lymphadenectomy can be considered if the nodal disease is resectable and

nonsystemic. Although not widely practiced, physicians have utilized radiation

therapy in lentigo maligna, nodular, ocular, head, and neck melanomas. It can

also be employed as palliative therapy in symptomatic and unresectable

metastases. In patients with systemic metastases, the median

survival time is six to eight months.3 Currently there are two

FDA-approved agents for systemic treatment of stage IV melanoma: dacarbazine

and aldesleukin (interleukin-2 [IL-2]). Although both agents have shown

moderate tumor response rates, there are no randomized clinical trials

available to support a significant survival benefit in utilizing systemic

therapy in metastatic malignant melanoma.14

Dacarbazine is a structural

analog of 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide (a precursor in purine biosynthesis).

It is proposed to act as an alkylating agent, interact with sulfhydryl

groups, and inhibit DNA synthesis. The recommended intravenous

treatment dose in metastatic malignant melanoma is 2 to 4.5 mg/kg/day for 10

days, repeated every four weeks or 250 mg/m2/day for five days,

repeated every three weeks. Common side effects include anorexia, nausea, and

vomiting. Although minimal, patients should also be monitored for bone marrow

suppression, alopecia, and fatigue.3,18 Dacarbazine has an overall

response rate of 22% and has the greatest effect on patients with low tumor

burden and nonvisceral metastases.1

Aldesleukin (Proleukin), a

human recombinant IL-2 product, is believed to have immunomodulatory and

antitumor activity in metastatic melanoma.3 The recommended

intravenous dose is 600,000 IU/kg (0.037 mg/kg) every eight hours for 14

doses. It is then repeated after nine days for a total of 28 doses per course.

The common side effects include hypotension, vomiting, diarrhea, and oliguria.

It is contraindicated in patients with organ allografts, abnormal thallium

stress test, or pulmonary function tests. There is a U.S. boxed warning for

aldesleukin that states high-dose therapy has been associated with capillary

leaking syndrome leading to severe hypotension, reduced organ perfusion, and

death. Due to potential for significant treatment-related toxicity, patients

should be closely monitored via baseline, routine physical exam, and

laboratory tests. Recommended tests include complete blood count with

differential, blood chemistries, chest x-ray (before and daily during

therapy), and hepatic and renal function (serum creatinine ?1.5 mg/dL prior to

starting treatment).19 Aldesleukin demonstrated the best clinical

response in patients with metastatic disease involving soft tissue and lymph

nodes with an overall median survival time of 11.4 months.14

Actinic Keratosis

Actinic keratoses

(AKs), also known as solar keratoses, are premalignant lesions that develop in

areas with chronic exposure to ultraviolet light.20 AKs are dry,

scaly, rough-textured patches that usually range in color from skin-toned to

reddish brown. The incidence of AKs increases with age. It is estimated that

approximately 60% of invasive SCC likely develop from AKs.21 The

diagnosis is generally based upon the clinical appearance, and treatment

depends on the size and quantity of lesions. Treatments for AKs include liquid

nitrogen cryotherapy, surgical destruction, photodynamic therapy, and topical

agents.22 Topical options include fluorouracil 5% topical cream,

diclofenac gel, and imiquimod cream.21

The Pharmacist's Role

Pharmacy professionals play a

critical and effective role in the education of patients.23

Opportunities to educate the public with respect to skin-protection strategies

should be proactively pursued by pharmacy professionals and should include

instructions to 1) avoid the sun, particularly between the hours of 10 am and

4 pm when the sun is strongest; 2) wear sunscreen with a sun-protection factor

of at least 15, applied 30 minutes prior to sun exposure; 3) wear protective

clothing; 4) wear a wide-brimmed hat and sunglasses that block both UVA and

UVB rays; and 5) avoid intentional tanning.8,24 Monthly self

examinations looking for the appearance of new moles or for changes in

pre-existing moles should also be encouraged. Moles that bleed, grow fast,

present scaly or crusted, do not heal, and/or itch should prompt a call or

visit to one's primary care provider (PCP). Areas of skin that feel rough

should also be brought to the attention of one's PCP.24 Patient

education regarding skin protection and self examination of the skin are two

of the many areas that pharmacy professionals can embrace to optimize patient

care and prevent adverse outcomes.

Acknowledgement for Peer Review

Donna Givone, PharmD, BCPP

Brett Geiger, PharmD

Clinical Pharmacy Specialists, Psychiatry

Jesse Brown VA Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois

Clinical Assistant Professors of Pharmacy Practice

University of Illinois College of

Pharmacy, Chicago, Illinois

REFERENCES

1. Neville JA,

Welch E, Leffell DJ. Management of nonmelanoma skin cancer in 2007. Nat

Clin Pract Oncol. 2007;4:462-469.

2. Skin cancer. National Cancer Institute. www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/skin. Accessed January 20, 2008.

3. Lang PG. Current concepts in the management of patients with melanoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2002;3:401-426.

4. Telfer NR, Colver GB, Powers PW. Guidelines for the management of basal cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:415-423.

5. Motley R, Kersey P, Lawrence C. Multiprofessional guidelines for the management of the patient with primary cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:18-25.

6. Wong CM, Strange RC, Lear JT.

Basal cell carcinoma. BMJ. 2003;327:

794-798.

7. Ives TJ. Photosensitivity and burns. In: Koda-Kimble MA, Young LY, Kradjan WA, Guglielmo BJ, eds. Applied Therapeutics: The Clinical Use of Drugs. 8th ed. New York, NY: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005:41.

8. Stulberg DL, Crandell B, Fawcett RS. Diagnosis and treatment of basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas. Am Fam Physician. 2004;70:1481-1488.

9. Lee S, Selva D, Huilgol SC, Goldberg RA, Leibovitch I. Pharmacological treatments for basal cell carcinoma. Drugs. 2007;67:915-934.

10. Fluorouracil 5% topical cream [package insert]. Humacao, PR: Oceanside Pharmaceuticals; 2006.

11. Aldara [package insert]. Northridge, CA: 3M Pharmaceuticals; 2005.

12. Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2007. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:43-66.

13. Corona R, Mele A, Amini M, et al. Inter-observer variability on the histopathologic diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma and other pigmented skin. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:1218-1223.

14. Markovic SN, Erickson LA, Rao RD, et al. Malignant melanoma in the 21st century, part 2: staging, prognosis, and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:490-513.

15. Runkle GP, Zaloznik AJ. Malignant melanoma. Am Fam Physician. 1994;49:91-104.

16. Crowson AN, Magro C, Mihm MC Jr. Unusual histologic and clinical variants of melanoma: implications for therapy. Curr Oncol Rep. 2007;9:403-410.

17. Eedy DJ. Surgical Treatment of Melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:2-12.

18. Dacarbazine for injection [package insert]. Paramus, NJ: Faulding Pharmaceuticals, 2002.

19. Proleukin [package insert]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals; 2000.

20. Jeffes EW III, Tang EH. Actinic keratosis. Current treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2000;1:167-179.

21. Kuflik AS, Schwartz RA. Actinic keratosis and squamous cell carcinoma. Am Fam Physician. 1994;49:817-820.

22. Harvie SE. Aminolevulinic acid and photodynamic combination therapy in the treatment of actinic keratoses: caring for the patient. Dermatol Nurs. 2007;19:31-4,39.

23. Mayer JA, Eckhardt L, Stepanski BM, et al. Promoting skin cancer prevention counseling by pharmacist. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:1096-1099.

24. "Safe-Sun" Guidelines. What are

the safe-sun guidelines? www.aafp.org/afp/20000715/375ph.html. Accessed

January 20, 2008.

To comment on this article, contact

rdavidson@jobson.com.