US Pharm. 2007;32(1)(Oncology suppl):22-28.

ABSTRACT: Emesis as an adverse event of

antineoplastic therapy can be troublesome for many oncology patients.

Inadequately controlling emesis can have a major impact on patient care and

may even lead to refusal of treatment. Antiemetic treatment guidelines have

been established to help health care professionals better understand and

effectively treat this unpleasant side effect of chemotherapy. The American

Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) previously created antiemetic treatment

guidelines to assist clinicians in caring for oncology patients dealing with

emesis. Recently, ASCO's Update Committee revisited the prior guidelines, as

well as any new literature available on treating chemotherapy-induced emesis;

as a result, a more comprehensive, updated version is now available. This

article presents the conclusions and recommendations set forth by the ASCO

committee regarding the management of antiemetics in oncology patients.

In early 2006, the American Society

of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) set out to update their 1999 treatment guidelines

regarding antiemetics in oncology.1 An Update Committee was formed

to assess all published literature pertaining to the use of antiemetics in

oncology from 1998 to February 2006. Data reviewed by the committee included

systematic reviews and meta-analyses, as well as randomized controlled trials.

When the committee reviewed

and analyzed the literature results, they focused on the incidence of complete

response--when there are no episodes of emesis and no rescue medications are

dispensed after antineoplastic therapy is administered. Compared to nausea,

complete response is the recommended clinical outcome measure for development

of the guidelines, due to its objectivity. In contrast, nausea--the patient's

perception that emesis may occur--is more subjective.

The committee also reviewed

the treatment guidelines discussed at the Antiemetic Consensus Conference,

hosted by the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC)

in 2004. This international conference facilitated consensus statements and

recommendations by representatives from nine oncology organizations, which

would be published in whole or in part with their individual organization's

antiemetic guidelines. This meeting took place in the hope that although

guidelines would inevitably differ between the associations, there would be a

smaller number of discrepancies between the individual documents on

antiemetics. The ASCO Update Committee used the findings from this meeting to

expand on their own recommendations and to aid in preparing their update

document.1

Impact and Risk Factors of

Chemotherapy-Related Emesis

Nausea and vomiting

are the two adverse effects involved with chemotherapy that tend to be the

most bothersome for patients and afflict the caregiver's or health care

professional's ability to appropriately treat a patient.2

Although nausea and vomiting seem common and devoid of significant harm, they

can cause dehydration, malnutrition, electrolyte imbalance, treatment delays

or refusal to continue treatment, and great discomfort.

Researchers have spent many

years trying to determine the physiological mechanism of emesis and have made

many strides toward effective therapies; however, the exact cause of emesis is

still not entirely understood. Today's studies on receptors found in the

chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ), e.g., dopamine, serotonin, and neurokinin,

have made great advances for patients prone to emesis during chemotherapy

treatment.2

There are several factors that

can raise the risk of nausea and vomiting, such as female gender, younger

patients (<50 years), those who have previously not improved with chemotherapy

regimens, and patients who do not have a history of chronic, high alcohol

intake and/or who experience significant fatigue.2 ,3

Non–patient-related factors that influence a patient's susceptibility to

emesis during treatment include the specific chemotherapy agent being used,

dose (especially high doses), schedule, and route in which the suspected agent

is given, as well as frequent-interval dosing and intravenous administration.

3 Nausea and vomiting can create additional havoc for patients already

coping with many other stresses. Consulting a health care professional about

risk factors and treatment options may reduce the risk of chemotherapy-related

emesis.

Types of

Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting

Patients can

experience nausea and vomiting minutes to hours after chemotherapy is

administered.1-3 This quick onset of emesis is considered acute

nausea and vomiting and usually ceases within the initial 24 hours after

therapy. When a patient experiences an episode that arises after the first day

following treatment, it can be classified as delayed nausea and vomiting

. Cisplatin is a prime example of emesis that can occur some time after

treatment. In some cases, cisplatin emesis may be at its most intolerable 48

to 72 hours after chemotherapy and can even extend up to seven days in some

cases. Anticipatory nausea and vomiting occurs when a patient has had a

previous negative experience with chemotherapy. This frequently happens in

patients who are preparing for their next treatment; they anticipate emesis

and consequently cause themselves to be sick. Breakthrough and

refractory nausea and vomiting are two other types of emesis that,

although uncommon, tend to arise in a certain subset of people. Breakthrough

vomiting occurs when the patient is undergoing current chemotherapy and is

receiving optimal antiemetic treatment but is still vomiting. Refractory

vomiting occurs after one or several chemotherapy cycles even though

antiemetic prophylaxis was used. The prophylaxis regimen is no longer

effective and the patient has stopped responding to the treatment.1-3

Emetic Risk Categories of Antineoplastic

Agents

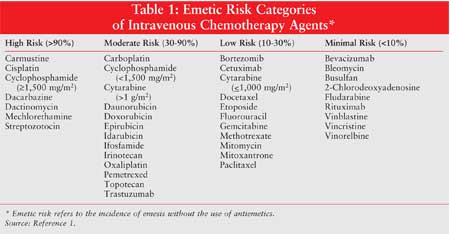

While a few antineoplastic agents

have unquestionably confirmed their potential to cause emesis after

administration, most agents are classified according to risk based on

experience.1,4 Antineoplastic agents are grouped by the degree of

emetic risk they pose. The percentage of emetic risk is a key factor in

deciding which antiemetic treatment should be employed. ASCO has instituted

four emetic risk categories that were adopted from the recommendations created

during the MASCC conference of 2004: high, moderate, low, and minimal emetic

risk (Table 1).1,4

Medications Used to Treat

Chemotherapy-Related Emesis

Treatment for

chemotherapy-related emesis has remained the same, to an extent.1

Along with standard medications used to treat this adverse effect, an

additional agent has become available that was not yet approved when ASCO

published its guidelines in 1999. Since the approval of aprepitant, it has

proven through numerous studies to be a worthy addition to the antiemetic

treatment regimen for oncology patients.1,2

5-Hydroxytryptamine-3

(5-HT3) Serotonin Receptor Antagonists: This class of

medication, which includes dolasetron, granisetron, ondansetron, palonosetron,

and tropisetron, has been the primary treatment for nausea and vomiting for

many years. 5-HT3 serotonin receptor antagonists work by blocking

serotonin release to the CTZ, alleviating emesis in most patients. Debate

still looms over which 5-HT3 antagonist is the preferred treatment;

while some studies have shown noninferiority among the agents, there are still

lingering questions regarding a possible superior agent.1

Corticosteroids:

While both dexamethasone and methylprednisolone have been used to treat

chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, dexamethasone is the most widely

available and commonly studied. The high therapeutic index of corticosteroids

and their efficacy as single agents in patients receiving chemotherapy of low

emetic risk establishes this class as the most frequently used antiemetics.

1

Neurokinin-1 (NK1

) Receptor Antagonists: The most recent agent included in the

antiemetic guidelines is the NK1 receptor antagonist known as

aprepitant.1 Aprepitant acts specifically on NK1

receptors in the brain and has little affinity for any other neurokinin

receptors. This NK1 receptor antagonist competitively inhibits

substance P from binding to NK1 receptors in the brain, thus

preventing emesis. Aprepitant is distinctive from other antiemetic agents in

regard to mechanism of action and its unique potential for CYP-related drug

interactions.1,2 Aprepitant serves as a substrate, as well as a

moderate inhibitor and inducer of cytochrome P-450 3A4 (CYP3A4) isoenzymes.

Aprepitant, acting as an inhibitor, can interact with corticosteroids (CYP3A4

substrates), causing the need for decreased dosing. In addition, several

chemotherapy agents (e.g., cyclophosphamide and docetaxel) are cleared by

CYP3A4, potentially inhibiting clearance of these drugs and increasing the

toxicity of some agents. There is no evidence of clinical complications when

aprepitant is given at its standard dose and schedule with chemotherapy.

1,2

Second-Line Agents:

Patients who are unable to tolerate or are refractory to first-line

antiemetics can use such agents as metoclopramide, butyrophenones,

phenothiazines, cannabinoids, benzodiazepines, and antihistamines. Lorazepam

and diphenhydramine can be used as adjuncts to first-line antiemetic regimens.

1

2006 Updated Guidelines

In June 2006, ASCO

released their most recent guidelines on the use of antiemetics in oncology.

Last updated in 1999,5 these guidelines have stayed the same in

various areas and have been modified or completely changed in others. All

treatment recommendations discussed refer to antineoplastic agents

administered intravenously.

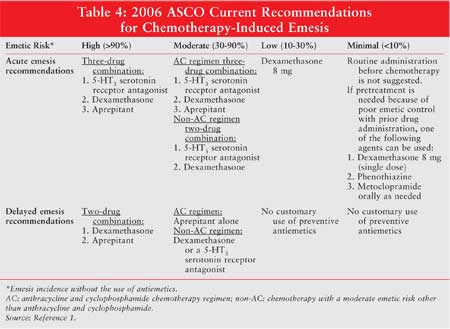

High-Risk Guidelines (>90%)

Acute Emesis

(0 to 24 hours after chemotherapy): In terms of treating

nausea and vomiting in patients who experience symptoms due to chemotherapy of

high emetic risk (cisplatin and noncisplatin groups) within 24 hours after

treatment, three agents are included in the 2006 guidelines.1 5-HT

3 serotonin receptor antagonists, corticosteroids (dexamethasone), and

aprepitant are all effective in the acute treatment of emetic symptoms related

to chemotherapy. The addition of aprepitant to ASCO's updated guidelines is

the one major difference from their previous recommendations. The Update

Committee, after analyzing numerous studies involving these three agents and

cisplatin, states that all three agents improve the symptoms of

cisplatin-induced emesis.1 The committee is able to generalize this

claim to include other agents in the high-risk emesis category due to the

universal incidence of emesis with cisplatin (>99%). The incidence is so great

that if an antiemetic agent is effective against cisplatin, efficacy against

other chemotherapy agents in this high-risk category is assumed.1,6

Delayed Emesis

(?24 hours after chemotherapy):

Recommendations for the prevention of delayed emesis in oncology patients

receiving cisplatin and other agents of high emetic risk include the use of

dexa methasone and aprepitant.1 This two-drug combination for

the prevention of cisplatin and noncisplatin delayed emesis is a change from

previous guidelines, which advised the use of a corticosteroid alone or

in combination with metoclopramide or a 5-HT3 antagonist.1

The combination of a 5-HT3 serotonin receptor antagonist with

dexamethasone is no longer recommended by the Update Committee due to study

results suggesting inferiority of the combination compared to dexamethasone

alone.7-9 Furthermore, a trial published in 2005 found

dexamethasone in combination with aprepitant superior to dexamethasone in

combination with ondansetron, thus supporting ASCO's most updated

recommendation of dexamethasone and aprepitant.10

Moderate-Risk Guidelines

(30% to 90%)

Acute Emesis:

This updated category includes some agents previously considered to carry

high emetic risk in the original 1999 guidelines.1 Currently, the

Update Committee recommends a three-drug combination--a 5-HT3

serotonin receptor antagonist, dexamethasone, and aprepitant--for all patients

receiving anthracycline and cyclophosphamide (AC). For patients who receive an

antineoplastic agent of moderate emetic risk other than AC, ASCO recommends a

two-drug combination: a 5-HT3 serotonin receptor antagonist and

dexamethasone.1 While this combination for all moderate-risk agents

(excluding AC) has not changed since the previous guideline,

aprepitant was added to regimens involving AC due to recent studies indicating

increased emetic potential with these two antineoplastic agents, along with

trials showing the efficacy of aprepitant against these agents.11

It is important to note that in this particular case, regardless of

aprepitant's potential CYP3A4 inhibition, the Update Committee advises that

the concomitant use of cortico steroids should not be reduced with the

administration of aprepitant.1

Delayed Emesis:

For patients who receive AC therapy, single-agent aprepitant should be

used to prevent delayed-onset emesis; this is a change from the original

antiemetic guidelines. Dexamethasone as a single agent or a 5-HT3

serotonin receptor antagonist is preferred for delayed emesis regarding all

other agents of moderate emetic risk. 1

Low-Risk Guidelines (10% to

30%)

Acute Emesis: The 1999

guidelines recommended no antiemetic agent for the prevention and/or treatment

of chemotherapy-induced emesis. However, the updated recommendations advise 8

mg of dexamethasone for the treatment of patients at low emetic risk. Although

the majority of patients given low-risk chemotherapy do not experience emesis,

many patients do undergo this side effect. No relevant clinical trials address

an optimal agent to be used for antineoplastics of low risk.1

Delayed Emesis:

Preventive use of antiemetic agents for delayed emesis is discouraged in

patients who receive low-risk chemotherapy.1

Minimal-Risk Guidelines

(<10%)

Acute and

Delayed Emesis: This risk category is a new addition in the 2006

antiemetic guidelines; a number of agents in this category were considered low

risk in 1999.1 Bleomycin, 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine, fludarabine,

vinblastine, and vincristine are among the chemotherapy agents that are now

categorized as minimal risk. Few antiemetic studies were appropriate for

guideline development regarding this risk category, since the risk of emesis

was so low in these agents. Trials assessing antineoplastics in this risk

category have not been conducted. Thus, recommendations are unchanged from the

original guideline for "low-risk" agents.

Regarding acute emesis with

minimal-risk agents, the routine administration of antiemetics is not advised.

Depending on the patient and history of poor emetic control with these agents,

a small percentage of patients may require pretreatment with antiemetics. In

these rare cases, a one-time dose of dexamethasone 8 mg, phenothiazine, or

metoclopramide (as needed) is common. Routine antiemetics for the prevention

of delayed emesis are also not indicated for agents in this category.

Other Emetic Problems

Combination

Chemotherapy: Guidelines remain unchanged for the use of antiemetics

in patients who receive combination chemotherapy regimens. Antiemetic

treatment should be determined based on the chemotherapy agent that poses the

greatest emetic risk.1

Numerous Consecutive

Days of Chemotherapy: Antiemetics appropriate to the specific risk

category of the chemotherapeutic agent should be administered for each day of

chemotherapy. This remains identical to the previous 1999 guidelines.1

Anticipatory Emesis:

Anticipatory emesis or conditioned emesis prevention and treatment guidelines

have not changed from the original recommendations. For the prevention of

anticipatory emesis, antiemetic treatment should be administered with initial

chemotherapy and should be the most appropriate choice in terms of emetic risk

for that particular chemotherapy agent. For the treatment of anticipatory

emesis, systematic desensitization, along with behavioral therapy, appears

effective and is recommended by the Update Committee. Although no prospective

trials have confirmed the efficacy of alprazolam and lorazepam in these

patients, both are recommended as treatment options by many committee members.

1

Emesis in Pediatric

Patients: Guidelines previously suggested the use of a 5-HT3

antagonist plus a corticosteroid in children receiving chemotherapy of high

emetic risk.1 Recent guidelines have expanded this recommendation

and now advise that moderate-risk chemotherapy be given with these

antiemetics. Cancer research involving the use of antiemetics in the pediatric

population is limited, but one important factor to be aware of in this

population is the large interpatient variations in clearance and metabolism of

antineoplastics. Due to this interpatient variation, substandard dosing of

antiemetic agents is possible.1 Higher weight–based dosing is

imperative in order to provide reliable protection against emesis in this

population.12,13

High-Dose Chemotherapy:

High-dose chemotherapy guidelines have not changed from the original

recommendations. A 5-HT3 serotonin receptor antagonist in

combination with a corticosteroid is advised in any patient who is receiving

an antineoplastic in extremely high doses. During their review of the

literature, ASCO found no existing study evaluating antiemetic agents in

high-dose chemotherapy. The Update Committee therefore recommends

investigation of aprepitant as a potential addition to this course of therapy

based purely on the highly emetic nature of increased doses of

antineoplastics. Caution is advised in patients who receive aprepitant for

this indication due to aprepitant's moderate CYP3A4 inhibition, potentially

leading to increased toxic effects of antineoplastic agents.1

Continued Emesis

Regardless of Prophylaxis: Despite treatment with recommended

antiemetic prophylaxis, emesis can still persist in some patients. The Update

Committee makes no change from previous guidelines and instead suggests that

health care professionals consider four elements: patient factors, antiemetic

regimen, addition of lorazepam or alprazolam, and the possibility of adding

either high-dose intravenous metoclopramide or a dopamine antagonist to the

treatment regimen.1

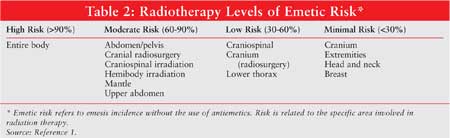

Radiation-Induced Emesis

Emetic risk associated with radiotherapy can vary depending on the type of treatment. Radiation therapy of high emetic risk can be difficult to control and occurs in a small number of patients. While the 1999 guidelines defined only three radiotherapy-induced emesis risk groups, the newest update from ASCO incorporated one additional emetic risk group (minimal risk [<30%]), which is seen in Table 2. 1

ASCO's current recommendations for

high radiation-induced emesis treatment are a 5-HT3 serotonin

receptor antagonist with or without a corticosteroid prior to each fraction

lasting at least 24 hours after treatment. Moderate- and low-risk

radiation-induced emesis recommendations involve administering a 5-HT3

serotonin receptor antagonist prior to each fraction. Lastly, in patients who

receive radiotherapy of minimal emetic risk, the Update Committee advises that

treatment be given on an as-needed basis with either dopamine or serotonin

receptor antagonists. The as-needed therapy should be continued

prophylactically for each additional radiation treatment day.1

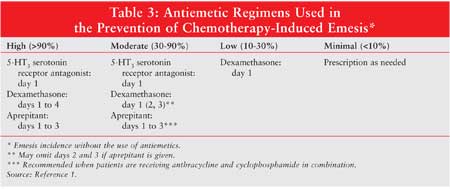

Conclusion

Table 3

addresses preferred drug regimens for each emetic risk category. Dosage,

schedule, and route of administration for these agents can be found in the

2006 ASCO update.1 Table 4 summarizes the recommendations

for chemotherapy-induced emesis.

While these guidelines provide a strong foundation on which clinicians can base their treatment decisions, they should not be used as the definitive resource. Adherence to these guidelines is voluntary, and ASCO maintains that each patient's circumstance is different and the guidelines should be applied appropriately. Much of the literature and clinical trials that were reviewed by ASCO's Update Committee do not address specific treatment decisions that come up in practice. Thus, these updated guidelines are not only accessible for current recommendations but can also be used as a starting point for investigation in the future.

References

1. Kris MG, Hesketh PJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline

for antiemetics in oncology: update 2006. J Clin Oncol.

2006;24:2932-2947.

2. Dando TM, Perry CM. Aprepitant: A review of its use in the prevention of

chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Drugs. 2004;64:777-794.

3. American Cancer Society. Nausea and Vomiting: Treatment Guidelines for

Patients with Cancer. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, 2005. Available at:

www.cancer.org/docroot/CRI/content/CRI_2_4_4x_NCCN_Nausea_and_

Vomiting_Treatment_Guidelines_for_Patients_with_Cancer.asp. Accessed October

2, 2006.

4. Grunberg SM, Osoba D, et al. Evaluation of new antiemetic agents and

definition of antineoplastic agent emetogenicity--an update. Support

Care Cancer. 2005;13:80-84.

5. Gralla RJ, Osoba D, et al. Recommendations for the use of antiemetics:

evidence-based, clinical practice guidelines. J Clin Oncol.

1999;17:2971-2994.

6. Hainsworth JD. The use of ondansetron in patients receiving multiple-day

cisplatin regimens. Semin Oncol. 1992;19:48-52.

7. Latreille J, Pater J, et al. Use of dexamethasone and granisetron in the

control of delayed emesis for patients who receive highly emetogenic

chemotherapy. National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J

Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1174-1178.

8. Roila F. Prevention of cisplatin-induced delayed emesis: still

unsatisfactory. Support Care Cancer. 2000;8:229-232.

9. Gridelli C, Ianniello GP, et al. A multicentre, double-blind, randomized

trial comparing ondansetron versus ondansetron plus dexamethasone in the

prophylaxis of cisplatin-induced delayed emesis. Int J Oncol.

1997;10:395-400.

10. Aapro MS, Schmoll HJ, et al. Comparison of aprepitant combination regimen

with 4-day ondansetron + 4-day dexamethasone for prevention of acute and

delayed nausea/vomiting after cisplatin chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol.

2005;23:730s. Abstract.

11. Warr DG, Hesketh PJ, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of aprepitant for

the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients with

breast cancer after moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol.

2005;23:2822-2830.

12. Allen JC, Gralla R, et al. Metoclopramide: dose-related toxicity and

preliminary antiemetic studies in children receiving cancer chemotherapy. J

Clin Oncol. 1985;3:1136-1141.

13. Tsuchida Y, Hayashi Y, et al. Effects of granisetron in children

undergoing high-dose chemotherapy: a multi-institutional, cross-over study.

Int J Oncol. 1999;14:673-679.

To comment on this article, contact

editor@uspharmacist.com.