US Pharm. 2008;33(3):59-65.

The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of

1990 (OBRA '90) included mandates for the states to improve understanding of

medications by Medicaid beneficiaries for whom they were prescribed and

dispensed.1 Although the Act was part of legislation passed in

1990, the pharmacy practice requirements did not go into effect until 1993.

While the original statute was aimed at Medicaid recipients, each state had

the option to adopt rules making those provisions applicable to other patients

as well. Some jurisdictions limited the directives to only new prescriptions

whereas others made the obligations applicable to both new and refilled

prescriptions. A patchwork quilt of requirements has also evolved regarding

whether the offer to counsel must be made personally by the pharmacist.

The various mandates of OBRA '90 are

reviewed and the responses of the states after enactment are highlighted. The

OBRA '90 mandates at the state level have played a part in a number of civil

law suits across the nation. Is there a private right of action for patient

injury attributable to a deviation from OBRA '90 mandates? How have courts

sorted through this set of professional obligations for the pharmacist?

Sufficient time has now passed to glean some lessons from these cases. Those

lessons from the past and lessons anticipated in the future will be

emphasized.

The shift in the focus of

pharmacists' education and practice activities from products to patients

gained momentum throughout the 1970s and 1980s, culminating in adoption of a

variety of federal mandates pertaining to pharmacy practice in the 1990 budget

bill enacted by Congress. The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990, known

colloquially as OBRA '90, was enacted toward the end of the Congressional

session to pull together in one piece of legislation all the

appropriations-related authorizations and requirements flowing from the

various Congressional enactments of the 101st Congress.

One of those components was a

set of provisions added to the federal statutory scheme governing federal

participation in the federal-state partnership program officially designated

Grants to States for Medical Assistance Programs, known in everyday parlance

as the Medicaid program. As Title XIX of the Social Security Act, this program

has both federal and state financial components, providing the federal

government with leverage to impose certain mandates on the states in order for

them to get the federal matching funds, which now can exceed 75% of the

program's cost to the state.2

The Statute at the Federal

Level

President George H.W. Bush signed

the bill into law on November 5, 1990, and the effective date of the

requirements related to pharmacy practice was established as January 1, 1993.

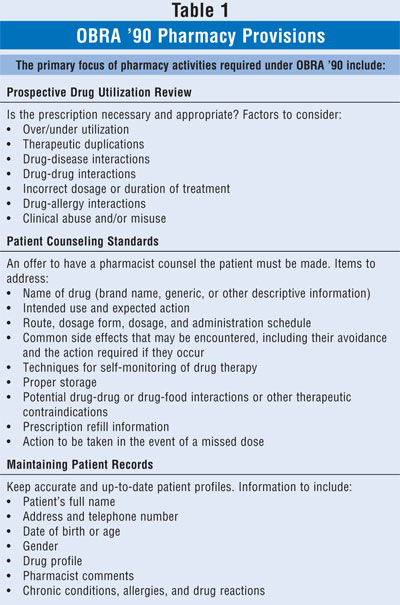

3 The federal statute had several major components: 1) Prospective Drug

Use Review, 2) Retrospective Drug Use Review, 3) Assessment of Drug Use Data,

and 4) Educational Outreach Programs. The first component (Prospective Drug

Use Review) has had the greatest impact on practice of the profession on a

daily basis. TABLE 1 provides a summary of the required pharmacy

activities.

The States Respond with

Statutes or Regulations

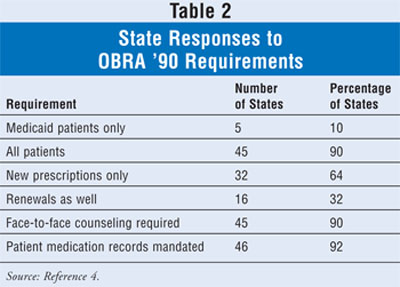

When these mandates

reached the states, officials with the Medicaid program, along with leaders of

the board of pharmacy or a similar administrative agency, began to formulate

their responses. Several decisions needed to be made--the cascading federal

mandate was for Medicaid beneficiaries only, but should this be extended to

all patients? Should the offer-to-counsel requirement be limited to newly

dispensed prescriptions or should it also include renewals? Must the offer to

counsel be extended by a pharmacy staff member or would a sign suffice? Must

the counseling be performed by the pharmacist face to face with the patient?

Should maintenance of patient medication records be mandated? How the states

are currently split on these questions, as reported by state boards of

pharmacy to the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy, is shown in

TABLE 2.4

The Courts Interpret OBRA

'90 in a Variety of Contexts

We can learn a variety of lessons

about how courts view pharmacy and pharmacists from case decisions where the

statutes or regulations were interpreted. But there is an important caveat to

bear in mind. The following cases only address issues considered by appellate

courts in published opinions. Except for cases in federal district courts,

there are no direct means to review decisions by state-level trial courts, as

very few opinions are released or reported in the legal literature.

|

Cases Addressing the Standard of

Care to Be Exercised by Pharmacists

In a case arising

before the January 1, 1993, effective date of the offer-to-counsel mandate,

the Court of Appeals of Georgia ruled that a pharmacist has no duty to warn a

patient of, or to refuse to dispense a medication in light of, a potentially

severe side effect arising from excessive dosage. Summary judgment entered for

the defendant pharmacy was upheld on appeal, but the court noted that this

"would not be controlling precedent for cases involving pharmacists' duties

arising after January 1, 1993."5

In a separate case arising

before the January 1, 1993, effective date of OBRA '90, the Florida Court of

Appeals ruled that a pharmacist who accurately dispensed medication but failed

to alert the patient or prescriber of potentially serious adverse drug

interactions has no duty to warn.6

A pediatric patient was

injured, and the question imposed on the pharmacist was whether the obligation

to offer to counsel the parents as the caregivers and agents of the patient

gives rise to a legal obligation related to the parents for their emotional

well-being, as opposed to the actual patient's well-being. The Supreme Court

of California ruled that no, this would be an "unwarranted enlargement of

potential liability."7

The Missouri Court of Appeals

reversed a summary judgment of the trial court granted in favor of the

defendant pharmacist where the lower court had ruled that the pharmacist's

"only obligation was to fill [sic] the prescriptions accurately." The case

involved a "strong hypnotic drug prescribed at three times the normal dose."

The court said, "Pharmacists are trained to recognize proper dose and

contraindications of prescriptions, and physicians and patients should welcome

their insights to help make the dangers of drug therapy safer." Summary

judgment was overruled and the case returned to the trial court for a decision

on whether the pharmacist met his legal duty under the facts of the case.

8

In another case, a woman

suffering an acute asthma attack entered the pharmacy and requested that the

pharmacist either give her an inhaler, for which she had no prescription on

record at this pharmacy, or call the physician or hospital to obtain a

prescription. The pharmacist would do neither, and the patient was taken by

ambulance to the hospital. The issue here was whether the pharmacist had a

legal duty to act arising from OBRA '90. The court ruled no; the OBRA '90

duties arise after receipt of a "prescription drug order." Absent a

prescription or a preexisting pharmacist-patient relationship, the pharmacist

had no legal duty to act.9

In an officially unpublished

opinion (that was nevertheless reported in a jurisprudence database), a

patient who declined counseling and signed a waiver form was not permitted to

later allege that he should have been counseled anyway. This was a very

interesting case where the patient made all sorts of convoluted arguments as

to why he should be allowed to maintain this claim, but in the end he not only

lost but had to pay the costs of the pharmacy chain's appeal.10

Cases Addressing the Issue

of "Mandatory" Copayments Reducing Reimbursement to Pharmacies

At issue in this

case was the provision in OBRA '90 that "reimbursement limits" may not be

modified by the federal government and that state governments may not "reduce

the limits for covered outpatient drugs" if the state's Medicaid plan was in

compliance with applicable federal regulations when certain emergency

regulations were adopted. The focus here was whether Pennsylvania's plan was

deemed to be "in compliance," meaning that no reduction in reimbursement was

permitted. The court ruled that yes, the state was in compliance, and

therefore was prohibited from reducing payments for covered outpatient

medications.11

The four-year moratorium on

reduction in medication reimbursement limits was also at issue in this case in

a U.S. district court in Florida. After the effective date of OBRA '90, the

Florida legislature passed an appropriations bill that implemented a copayment

feature for the state's Medicaid drug program. Reimbursement rates to

pharmacies were not altered, but the state agency charged with administering

the program automatically reduced payments to providers by the amount of the

copayment. Further, federal program requirements prohibit a participating

provider from denying services to a program participant who cannot pay the

cost-sharing amount. The Florida Pharmacy Association advanced the argument

that this amounted to a reduction in reimbursement, a violation of the OBRA

'90 moratorium. The court did not agree. In its view the pharmacies now have

two sources of reimbursement--state plus patient--rather than one as before,

stating that "whether one of the sources, the recipients, may not be so

forthcoming with reimbursement does not change the fact that the reimbursement

limits have not been changed."12

The copayment implemented for

Medicaid-covered medications in Nebraska presented issues parallel to those in

the Florida case discussed above. Noting that authorization for states to

implement copayments in the Title XIX drug program had been in place since

1982, the court ruled that the defendant state officials "have ordered that in

certain cases a pharmacist may never actually recover the reimbursement limits

notwithstanding the fact that the pharmacist would theoretically be eligible

for maximum reimbursement. The plain words of the federal statute prohibit

this practice." Waxing poetic, the judge in the case continued, "This case

brings to mind Gertrude Stein's familiar words: 'A rose is a rose is a

rose'...A reduction is a reduction, whether by change in a formula or

otherwise."13

Indiana's plan had a 50 cent

copayment for generic medications and a dollar copayment for brand name

products at that time. And the court there quickly grasped the issue. "While

the Moratorium clearly prohibits a decrease in ëreimbursement level,' it does

not explicitly state how the copayment provisions, which predates the

Moratorium, is to be affected." In the end, the request of the Indiana

Pharmacists' Association for an injunction prohibiting such action by the

state government was granted.14

The federal district court in

Indiana noted that "the State is able to reduce its reimbursement liability to

pharmacists not only by the amount of copayments that are collected by

pharmacists, but also by the amount of copayments the pharmacists are unable

to collect because of the patient's inability to pay." It was estimated that

50% of Medicaid recipients could not afford the copayment. The state agency

argued that the federal statute prohibits reducing "payment limits," which it

was not doing; it was reducing the actual amount paid. The court rejected that

interpretation, concluding that "in enacting the moratorium, Congress intended

to protect the actual level of reimbursement flowing to pharmacists."

15

Case Addressing Issues with

Mandatory Rebates from Manufacturers

The Pharmaceutical

Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) challenged the provision in

Michigan's OBRA '90 authorized program whereby states established preferred

drug lists for Medicaid and required prior authorization for coverage of

nonpreferred medications that had generated insufficient rebates for the

state. The state's program was upheld.16

Conclusions

The five cases that

address pharmacy reimbursement are likely last words on that issue based on

OBRA '90 provisions, given that the moratorium on states altering the methods

of calculating fees and benefits has since expired. This is not to say that

there are not still, and probably always will be, reimbursement disputes.

Likewise, rebate issues will linger as well. It has been noted that "as more

courts are asked to address the legal standard of pharmacy practice, they will

turn to OBRA '90 to assist them in defining those standards. OBRA '90 mandates

that pharmacists take on additional responsibilities, and with those expanded

responsibilities come expanded expectations and liability."17

Given that there are only six published opinions that address the standard of

care exercised by pharmacists over the past few years using OBRA '90 language,

it is fair to conclude that this statute has not caused the revolution in

pharmacist counseling that some commentators or observers predicted at the

time of its enactment and implementation. It is commonly observed that the

wheels of justice turn slowly. Given this, there is still hope that OBRA '90

still be considered a planted seed that yields a change in the communications

relationships between pharmacists and patients.

Adapted from a poster presented at the

American Society for Pharmacy Law 32nd Annual Meeting/American Pharmacists

Association 154th Annual Meeting, Atlanta, Georgia, March 16-19, 2007, and

winner of the Research Award from the American Society for Pharmacy Law, 2007.

REFERENCES

1. P.L. 101-508, 104 Stat. 1388, codified at 42 U.S.C. ßß1396r-8g.

2. Ku L, Park E. Federal aid to state Medicaid programs is falling while the economy weakens. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. October 26, 2001. www.cbpp.org/10-11-01health.htm. Accessed February 26, 2008.

3. Medicaid program. Fed Regist. 1992;57:49397-49401.

4. Survey of Pharmacy Law. Sec. XXIII-Patient Counseling Requirements. Mount Prospect, IL: National Association of Boards of Pharmacy CD-ROM; 2007:75-76.

5. Walker v. Jack Eckerd Corp , 434 S.E.2d 63 (Ga. App. 1993).

6. Johnson v. Walgreen Co., 675 So.2d 1036 (Fla. App. 1996).

7. Huggins v. Longs Drug Stores California, Inc., 862 P.2d 148 (Cal. 1993).

8. Horner v. Spalitto, 1 S.W.3d 519 (Mo. App. 1999).

9. Chiney v. American Drug Stores, Inc., et al., 21 S.W.3d 14 (Mo. App. 2000).

10. Hooper v. Thrifty Payless, Inc ., 2003 Cal. App. Unpub. Lexis 11715 (2002).

11. Pennsylvania Pharmaceutical Association, et al. v. Casey, et al., 800 F.Supp 173 (M.D. Pa. 1992).

12. Florida Pharmacy Association, et al. v. Williams, et al., 871 F.Supp. 1441 (N.D. Fla. 1993).

13. Nebraska Pharmacists Association, Inc, et al. v. Nebraska Department of Social Services, et al., 863 F.Supp 1037 (D. Neb. 1994).

14. Indiana Pharmacists' Association, et al. v. Indiana Family and Social Services Administration, 881 F.Supp. 395 (S.D. Ind. 1994).

15. Pharmaceutical Society of the State of New York, Inc. v. New York State Department of Social Services, et al., 50 F.3d 1168 (2nd Cir 1995).

16. Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, et al. v. Thompson, 259 F.Supp.2d 39 (D.D.C. 2003).

17. Fink JL III, Vivian JC,

Bernstein IG, eds. Pharmacy Law Digest. 40th ed. St. Louis, MO: Wolters

Kluwer Health; 2005:98-99.

To comment on this article, contact

editor@uspharmacist.com.