US

Pharm. 2006;4:54-62.

With the rise in popularity

and success of radical weight-loss surgery among obese persons, a new

postoperative cosmetic challenge has emerged. Following massive weight loss

achieved by diet, exercise, gastric bypass, or gastric banding, the patient

typically has significant areas of excess skin, commonly including on the

abdomen, breasts, arms, and thighs. Skin will progressively sag in

characteristic as well as idiosyncratic patterns like melting wax from a

burning candle. No amount of exercise or special diets will tighten it. Total

body lift surgery addresses the entire skin laxity problem of the trunk and

thighs. The transverse removal of unwanted skin and fat is followed by tight

closure, which in effect lifts the lower adjoining region. While the

improvements are dramatic, this is major surgery that comes with serious risks

and impressive scars.

Wound Healing

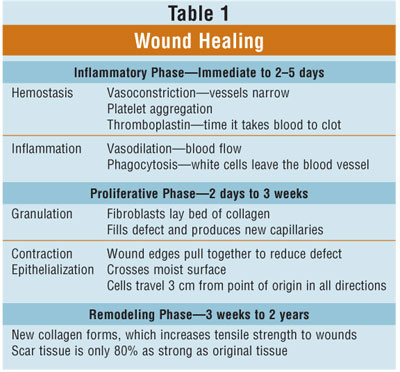

The wound healing

process (TABLE 1) is a complex series of events that begin at the moment of

injury and continue for months to years. A thin coagulum of fibrin (from the

tissues and serum) and red blood cells forms a clot that unites the edges of

the wound. Eventually the clot is replaced by granulation tissue, a connective

tissue with a rich blood supply. Scars are red because of increased small

vessels, and the color gradually fades to white as the vascularization

decreases and the collagen matrix matures. Remodeling of the collagen matrix

may continue for years depending on individual genetics and age. In general, a

thin pale long scar remains when the scars are mature.

Many variables can affect the

severity of scarring, including the size and depth of the wound, the blood

supply to the area, the thickness and color of the skin, and the direction of

the scar. How much the appearance of the scar bothers a patient is, of course,

a personal matter. While no scar can be removed entirely, its appearance can

be improved. The de gree of improvement depends on the size and direction of

the scar, the nature and quality of the person's skin, and how well the person

cares for the wound after the operation.

Two Types of Scars

Keloids are

thick, puckered, itchy clusters of scar tissue that grow beyond the edges of

the wound or incision. They are often red or darker in color than the

surrounding skin. Keloids occur when the body continues to produce the tough,

fibrous protein known as collagen, after a wound has healed. Keloids can

appear anywhere on the body, but they are most common over the breastbone, on

the earlobes, and on the shoulders. They occur more often in dark-skinned

people than in those who are fair-skinned. The tendency to develop keloids

lessens with age. Hypertrophic scars are often confused with keloids, since

both tend to be thick, red, and raised. Hypertrophic scars, however, remain

within the boundaries of the original incision or wound.

Treatment Methods

Keloids can be treated

aggressively and early by injecting a steroid medication directly into the

scar tissue to reduce redness, itching, and burning. In some cases, this will

also shrink the scar. If steroid treatment is inadequate, the scar tissue can

be cut out and the wound closed with one or more layers of stitches. This is

generally performed under local anesthesia as an outpatient procedure, and

stitches are removed in a few days. Unfortunately, keloids tend to recur,

sometimes larger than before. In some cases, application of a pressure garment

over the area is recommended for as long as a year. Keloids may return at any

time, requiring repeated procedures, but this is not common.

Hypertrophic scars often improve

on their own--though it may take a year or more with the help of steroid

applications or injections. If a conservative approach does not appear to be

effective, hypertrophic scars can often be improved surgically. The plastic

surgeon will remove excess scar tissue and may reposition the incision so that

it heals in a less visible pattern. The surgery may be done under local or

general anesthesia, depending on the scar's location and what the patient and

surgeon decide. The patient may receive steroid injections during surgery and

at intervals for up to two years afterward to prevent the thick scar from

forming again.

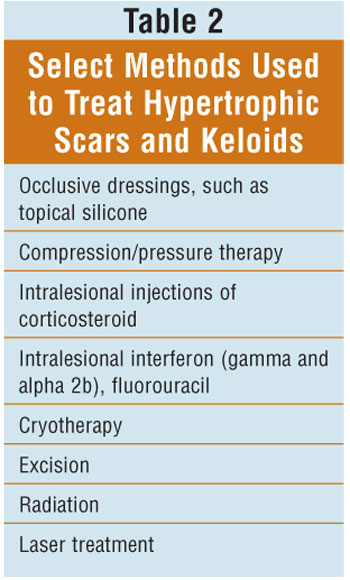

Differentiating hypertrophic scars

from keloids can be challenging. Scars can range between those that become

hypertrophic in the first few months and then completely resolve with no

treatment, to the keloids that become disfiguring and permanent. Table 2 shows

methods used to treat scars.

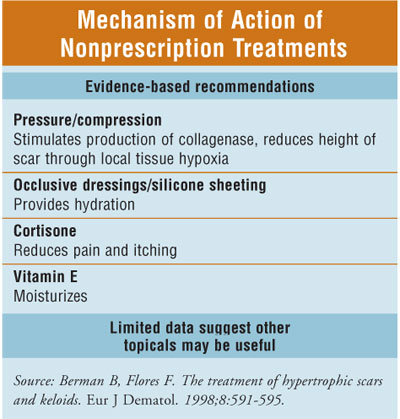

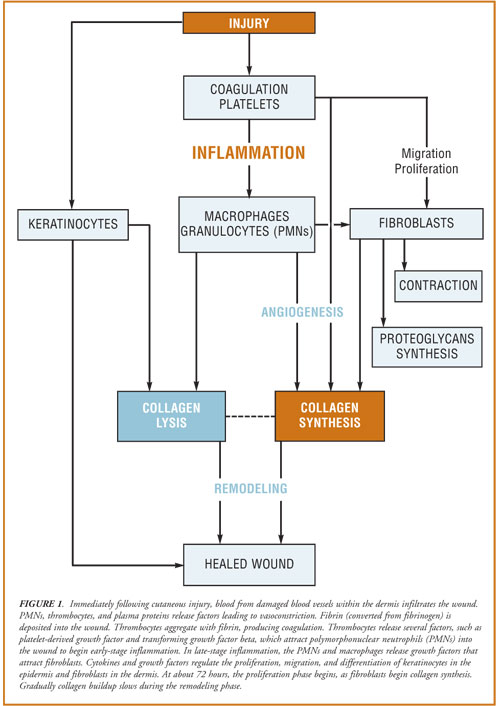

Silicone gel sheeting has been a

widely used option for hypertrophic scars and keloids since the 1980s. The

mechanism of action of topical silicone is unknown but there are temperature

differences as small as 1°C under silicone gel sheeting. This could have a

profound effect on collagen kinetics and may reduce scarring. Silicone itself

has never been found in significant amounts in scars treated with sheeting, so

a direct chemical effect is unlikely. It has also been theorized that static

electricity generated by silicone gel sheeting induces a polarization of scar

tissue that results in involution. Occlusion of scars by silicone gel sheeting

might alter cytokine levels, which in turn would have an effect on scar

remodeling (Figure 1).

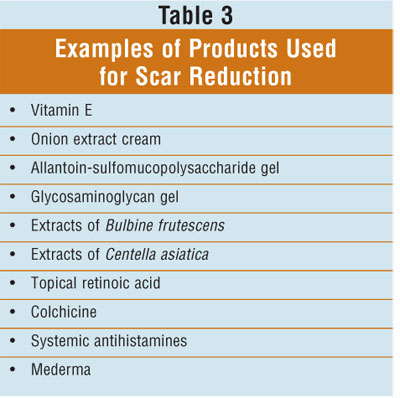

Table 3 lists additional

treatments that can be used to improve the appearance of scars. If the scar

requires more intensive treatment, additional options include dermabrasion,

scar revision surgery, cortisone injections, cryosurgery, and laser

resurfacing. A useful graded protocol to manage postoperative scarring starts

with patients using silicone gel sheeting at three to four weeks. The

application of adhesive microporous hypoallergenic paper tape after surgery is

frequently successful. The mechanism of benefit is unknown, but it may in part

be mechanical (pressure) and/or occlusive.

Adapted from Total Body Lift by

Dennis J. Hurwitz, MD, FACS, Director, Hurwitz Center for Plastic Surgery,

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

To comment on this article,

contact editor@uspharmacist.com.