US Pharm. 2008;33(7):HS-4-HS-10.

It is estimated that at least 4.5 million U.S. adolescents are cigarette smokers.1 Most adolescent smokers (90%) will become adult smokers with serious health problems.2 The consequences of smoking in adulthood are well known; nonetheless, initiation of tobacco use in adolescents continues to be the primary reason for addiction in adults. Adolescent smokers have been shown to suffer from health and educational consequences that may influence their entire adult life.3 The American Cancer Society has set a challenge goal to reduce the current number of youth smokers (age under 18 years) to 10% by the year 2015.2

The general belief is that tobacco dependence is a public health problem involving adults, but adolescents share this addiction with their adult counterparts. According to the Global Youth Tobacco Survey, American adolescents have the highest prevalence of smoking (22%) compared with 132 other countries.4 Previously it was reported that adults aged 45 to 64 years had the highest smoking rate, with a prevalence of 23%.5 However, it has recently been reported that one in four high-school seniors smokes at least once a month.6

How Nicotine Affects the Brain

Nicotine activates cholinergic receptors in the brain that are usually activated by acetylcholine. Acetylcholine is produced in the brain and the peripheral nervous system. Because the chemical structure of nicotine is similar to that of acetylcholine, it is also able to activate cholinergic receptors. Long-term nicotine use causes modifications in the number of cholinergic receptors and in the sensitivity of the receptors to nicotine and acetylcholine. These changes may be to blame for the development of nicotine dependence. When dependence occurs, the smoker must regularly supply the brain with nicotine in order to maintain normal brain functioning. If nicotine levels drop, the smoker will begin to feel uncomfortable and have withdrawal symptoms.7

Nicotine also stimulates dopamine in the midbrain. This release of dopamine is similar to that seen with drugs such as heroin and cocaine and is thought to bring about the satisfying sensations experienced by many smokers.

Reasons for Smoking

Adolescent smoking was once thought to be a social aspect of teenage development rather than an addiction. However, the reasons that adolescents start to smoke are different from what they were previously thought to be. Children as young as grade-school age are becoming habitual smokers, not because of peer pressure but because they enjoy the way smoking makes them feel. A recent survey conducted by the University of Massachusetts found that children enjoy the relaxing feelings associated with cigarette smoking.8 Researchers found that children are addicted from their first puff of a cigarette.8 Previous exposure to tobacco advertisements also played a part in whether or not a child decided to pick up a cigarette; the amount of contact with tobacco-company mascots like Joe Camel significantly influenced a child's future smoking decisions.9 Additionally, it has been found that a child who has a parent who smokes is more likely to become a smoker.10

Assessing Adolescent Addiction

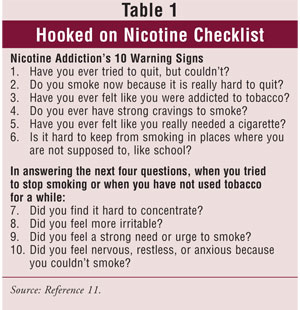

Addiction in adolescents is assessed with different tools than those typically used for adults. The Hooked on Nicotine Checklist (TABLE 1) and the Nicotine Dependence Scale for Adolescents are used as measurement scales to assess addiction in this age group.10,11

Nonpharmacologic Treatments

Currently, data regarding smoking-cessation treatment in adolescents are limited. Smoking-cessation initiatives in adolescents are very important for decreasing the rate of lifelong smokers; however, never taking that first cigarette puff is the best and most cost-effective method of smoking cessation.12 Other modalities are needed to help addicted teens quit. Curry et al found that young-adult smokers received fewer smoking-cessation interventions from their physicians than adults did.13 Interventions tailored to adolescents, like quit-line services and media-promotion campaigns, were found to motivate young smokers more than adults.14 Programs that offer school-based, multiple-session, smoking-cessation counseling in high schools were found to be more effective than simply providing informational pamphlets. 15 Not-On-Tobacco (also called N-O-T) is a school-based, 10-session voluntary program developed by the American Lung Association that is designed to help high-school students stop smoking.16

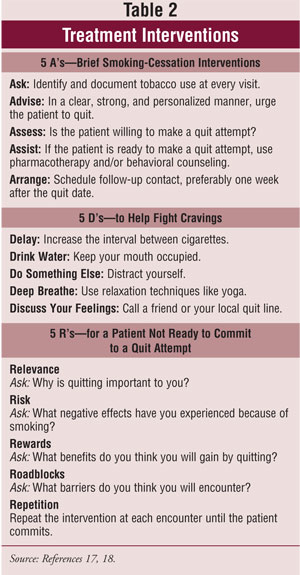

If an adolescent is ready to quit, nonpharmacologic behavioral modification should be initiated immediately. See TABLE 2 for some examples. The "5 A's" and "5 D's" are brief standard interventions that can be used by a clinician or by anybody conducting a quit session, and the "5 R's" are useful in working with an adolescent who is not yet ready to commit to a quit date.17,18

Pharmacologic Treatments

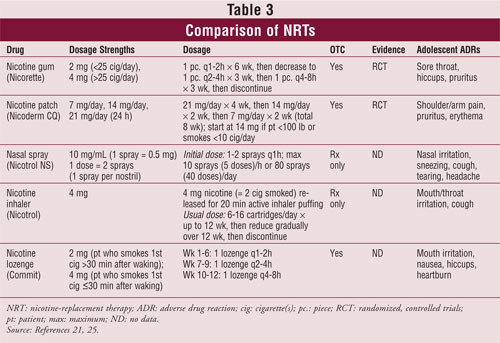

Nicotine-Replacement Therapy (NRT): NRTs are first-line medications approved by the FDA for use as smoking-cessation aids in adults. In 2001, The American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Substance Abuse's statement on tobacco use suggested that individuals who smoke more than 10 cigarettes per day might benefit from NRT. 19 NRTs are available as patches, gums, inhalers, lozenges, and nasal sprays. These medications have not been approved for use in patients aged 17 years and younger. Randomized, controlled trials examining the safety and efficacy of NRTs in adolescents have concluded that the products are effective and that they have adverse drug reaction rates comparable to those in adults. 20,21 Moolchan et al looked at 12 weeks of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) plus the nicotine patch, nicotine gum, or placebo in patients 13 to 17 years old.21 They found that the combination that best decreased the number of cigarettes smoked was the patch plus CBT, but abstinence rates were comparable at three months posttreatment across the board regardless of treatment group; the patch induced a quit rate of 18% compared with gum (6.5%) and placebo (2.5%) at three months.21

It has been reported that NRT use in adolescents has the potential to cause addiction at lower and less frequent doses and that it may potentially lead to misuse.10 According to other research, however, NRT is not dangerous for adolescents and does not appear to have much abuse potential.22-24 The various products at the usual doses are shown in TABLE 3.25

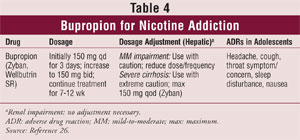

Bupropion: Bupropion is a non-nicotine medication approved for smoking cessation in adults. It first appeared on the market as Wellbutrin SR, under which name it is used to treat depression. As an off-label indication, bupropion is also used to treat the symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children. Sustained-release bupropion (under the name Zyban) is approved by the FDA to treat tobacco dependence (TABLE 4). Bupropion has a boxed warning for suicidal ideation in children. This medication should not be used in patients with a history of seizures, bulimia, or anorexia.

A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial examined cessation rates with two different total daily doses of bupropion (150 mg, 300 mg) in 312 subjects aged 14 to 17 years who smoked at least six cigarettes a day.26 After six weeks, the abstinence rate in the 300-mg group was statistically significantly higher than in the 150-mg group (29% vs. 16%, respectively).27 This trial showed equivocal support for using certain adult smoking-cessation medications in adolescents.27 Based on the safety data from this trial, it could be extrapolated that this medication is safe for use in adolescents.

Varenicline: Varenicline (Chantix), which is used only in adults, is a partial agonist selective for alpha-4 beta-2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes. Varenicline mimics the effect of nicotine by activating these brain receptors, which maintain low-dose stimulation of dopamine, thereby preventing cravings. Varenicline is also a nicotine antagonist; it blocks nicotine from entering the brain, thus eliminating the pleasurable feelings associated with smoking.10 Dose is not related to the quantity of cigarettes smoked. The usual starting dose is 0.5 mg daily for the first three days, then bid for days 4 through 7; the dose is then increased and maintained at 1 mg bid for a total of 12 weeks.

In late 2007, the FDA advised prescribers of potential neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients treated with varenicline. Additionally, the FDA issued a Public Health Advisory in February 2008 to inform health care providers (HCPs), patients, and caregivers of new safety warnings regarding varenicline.28 The jury is still out as to whether these symptoms were caused by complications due to nicotine withdrawal or by the drug itself. These symptoms were reported to persist even in patients who did not quit smoking, but continued treatment with varenicline. All patients being treated with varenicline should be observed for neuropsychiatric symptoms, including behavioral changes, agitation, depressed mood, suicidal ideation, and suicidal behavior. In postmarketing reports, these symptoms, as well as worsening of pre-existing psychiatric illness, have been noted in patients attempting to quit smoking while taking this drug. Patients with serious psychiatric illnesses such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder did not participate in premarketing studies of varenicline, and the safety and efficacy of this drug in these patients has not been established. HCPs and caregivers should be aware of the need to monitor for these symptoms, and caregivers should report such symptoms immediately to the patient's HCP.

Varenicline is not approved for use in adolescents. To date, there are no published trials evaluating its use in this population; however, Pfizer will be conducting a study to determine whether varenicline is safe and effective for use for smoking cessation in patients aged 12 to 16 years. If studied appropriately and found to be safe in adolescents, this medication would be a useful addition to the limited number of drugs available to treat cigarette smoking in adolescents.

The Pharmacist's Role

Pharmacists are in a prime position to intervene when presented with a teen smoker. Pharmacists may offer behavioral counseling or pharmacologic treatment in community- and hospital-based ambulatory settings. They can educate teens about the long-term effects of smoking and should focus on smoking risks that might be most meaningful to young people: premature aging, staining of teeth and nails, and smoker's breath. The OTC availability of the majority of NRT products allows retail pharmacists to tailor smoking-cessation treatments and offer consistent follow-up to identified patients. The accessibility of community pharmacists permits interventions not only with the teen smoker, but potentially with the parent as well.

Pharmacists practicing in hospital settings can assist teen smokers by identifying their smoking status while admitted. Once smoking status is identified, educational brochures can be provided and readiness to quit should be assessed. The patient should then be referred to a smoking-cessation clinic. If warranted, smoking-cessation pharmacotherapy may be initiated with appropriate follow-up.

Conclusion

There has been much advancement in the area of smoking-cessation efforts over the last 10 years. Researchers have begun to look more closely at adolescent smokers in clinical trials and to attempt to determine safe and effective treatments for this special population. More research is needed, however, to facilitate the efforts of practitioners working in this area. Continued research, increased awareness by youths of smoking-related illnesses, and outreach programs all can help adolescents to never pick up a cigarette or to finally put the cigarette down.

REFERENCES

1. American Lung Association. Adolescent smoking statistics. November 2003. www.lungusa.org/site/pp.asp?c=dvLUK9O0E&b=39868. Accessed January 17, 2008.

2. American Cancer Society. Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2006. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2006.

3. Charlton A, Blair V. Absence from school related to children's and parental smoking habits. BMJ. 1989;298:90-92.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of cigarettes and other tobacco products among students aged 13-15 years--worldwide, 1999-2005. MMWR. 2006;55:553-556.

5. Pray WS, Pray JJ. Nonprescription options for smoking cessation. US Pharmacist. 2003;28(2):8-12.

6. Liu J, Peterson AV, Kealey KA, et al. Addressing challenges in adolescent smoking cessation: design and baseline characteristics of the HS Group-Randomized trial. Prev Med.2007;45:215-225.

7. NIDA for Teens. Mind Over Matter: teacher's guide. Nicotine mechanism of action. http://teens.drugabuse.gov/mom/tg_nic2.asp. Accessed January 14, 2008.

8. DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Fletcher K, et al. Symptoms of tobacco dependence after brief intermittent use: the Development and Assessment of Nicotine Dependence in Youth-2 study. Arch Pediatr Adol Med. 2007;161:704-710.

9. Arnett JJ, Terhanian G. Adolescents' responses to cigarette advertisements: links between exposure, liking, and the appeal of smoking. Tob Control. 1998;7:129-133.

10. Treating tobacco addiction. In: City Health Information. New York, NY: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. December 2007/January 2008;27:1-8.

11. WhyQuit.com. Youth nicotine dependency test. http://whyquit.com/whyquit/LinksYouth.html. Accessed January 14, 2008.

12. Husten CG. Smoking cessation in young adults. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1354-1356.

13. Curry S, Sporer AK, Pugach O, et al. Use of tobacco cessation treatments among adult smokers: 2005 National Health Interview Survey. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1434-1443.

14. Cummings SE, Hebert KK, Anderson CM, et al. Reaching young adult smokers through quitlines. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1402-1405.

15. Adelman WP, Duggan AK, Hauptman P, Joffe A. Effectiveness of a high school smoking cessation program. Pediatrics. April 2001;107:e50. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/content/abstract/107/4/e50. Accessed January 9, 2008.

16. American Lung Association. Not-On-Tobacco (N-O-T) backgrounder. A total health approach to helping teens stop smoking. www.lungusa.org/site/pp.asp?c=dvLUK9O0E&b=39866. Accessed January 11, 2008.

17. National Advisory Committee on Health and Disability. Guidelines for Smoking Cessation, Revised 2002. Wellington, New Zealand: National Advisory Committee on Health and Disability (National Health Committee); May 2002.

18. US Public Health Service. Treating tobacco use and dependence--clinician's packet. A how-to guide for implementing the Public Health Service clinical practice guideline. 2003. www.surgeongeneral.gov/tobacco/clinpack.html. Accessed January 11, 2008.

19. AAP Committee on Substance Abuse. Tobacco's toll: implications for the pediatrician. Pediatrics. 2001;107:794-798.

20. Hurt RD, Dale LC, Fredrickson PA, et al. Nicotine patch therapy for smoking cessation combined with physician advice and nurse follow-up. One-year outcome and percentage of nicotine replacement. JAMA. 1994;271:595-600.

21. Moolchan ET, Robinson ML, Ernst M, et al. Safety and efficacy of the nicotine patch and gum for the treatment of adolescent tobacco addiction. Pediatrics. 2005;115:407-414.

22. Hanson K, Allen S, Jensen S, Hatsukami D. Treatment of adolescent smokers with the nicotine patch. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5:515-526.

23. McNeil A, Foulds J, Bates C. Regulation of nicotine replacement therapies (NRT): a critique of current practice. Addiction. 2001;96:1757-1768.

24. West R, Hajek P, Foulds J, et al. A comparison of the abuse liability and dependence potential of nicotine patch, gum, spray and inhaler. Psychopharmacology (Berlin). 2000;149:198-202.

25. Lexi-Comp Online. http://crlonline.com/crlonline. Accessed January 17, 2008.

26. Muramoto ML, Leischow SJ, Sherrill D, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 2 dosages of sustained-release bupropion for adolescent smoking cessation. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:1068-1074.

27. Colby SM, Gwaltney CJ. Pharmacotherapy for adolescent smoking cessation. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;298:2182-2184.

28. FDA issues Public Health Advisory on Chantix. FDA News. February 1, 2008. www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/NEWS/2008/NEW01788.html. Accessed April 15, 2008.