US Pharm. 2007;32(4)(Oncology suppl):25-31.

Skin cancer occurrence in organ transplant recipients (OTRs) is a rising phenomenon. Immunosuppressed OTRs are 65 times more likely to develop a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), which usually behaves more aggressively than in the general population.1 Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the second most common skin cancer in immunosuppressed OTRs, with an associated risk 10 times that of the general population.1 Up to 45% of heart, liver, and kidney transplant recipients develop skin cancer or premalignant actinic keratoses (AK) lesions within five–10 years after transplantation.1 Some risk factors for the disease in transplant recipients include light hair, eyes, and skin; extensive freckling; extensive sun exposure; family and/or personal history of skin cancer; older age; infections of the skin with human papilloma virus; duration and intensity of immunosuppressive therapy; and a place of residence at a latitude near the equator or high altitude.1 The drug therapy regimen for OTRs is a careful balance of graft rejection prevention versus the risk of adverse effects associated with therapy, including malignancy.

Uses

Aldara (imiquimod) cream is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for

the topical treatment of superficial BCC and AK in immunocompetent adults.

2 Typically, treatment for most skin carcinomas includes curettage,

electrodessication, excisional removal, radiation, cryosurgery or laser

surgery and photodynamic therapy. Presently, clinicians use imiquimod to treat

carcinomas in OTRs who failed to fully respond to traditional therapies.

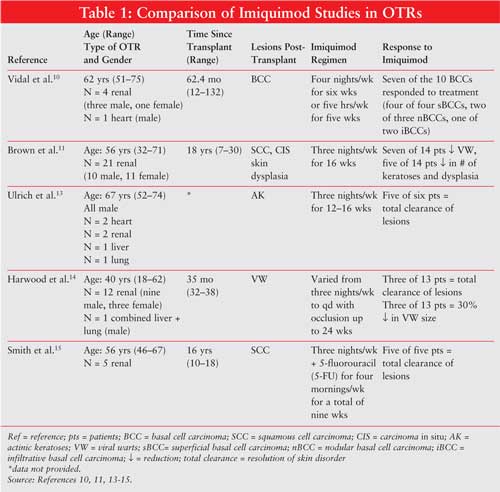

This article reviews the clinical safety and efficacy of topical imiquimod therapy administered to immunosuppressed OTRs. TABLE 1 illustrates specific patient demographics, time since transplant, imiquimod regimens, and patient responses.

Pharmacology

Topical administration of imiquimod 5% cream induces an immune response by

binding to toll-like receptor 7 (TLR-7). This enhances cell-mediated cytolytic

antiviral activity by activating macrophages to release pro-inflammatory

mediators: interferon (IFN)-alpha, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha,

interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and IL-12, among others.3-6

TLR-7 is abundant in the heart, spleen, bone marrow, and lymph nodes.7

Release of proinflammatory mediators activates a type 1 cell-mediated immune

response (Th1), which is thought to be the mechanism behind imiquimod's

immunomodulating effects.6 Commonly seen local skin reactions, such

as erythema (69%), edema (71%), induration (78%), erosions (54%), and scabbing

(64%), are considered signs of imiquimod's local immune response.2

These adverse events are actually considered markers of therapeutic efficacy.

Increased severity of erythema, erosion, and scabbing are associated with a

higher rate of response (clearance of lesions).8

Theoretically, systemic absorption of an immunomodulator drug may increase the risk of an organ graft rejection. Yet, imiquimod does not appear to be systemically absorbed, as quantifiable amounts (?5 ng/mL) were not recovered from blood samples taken at week 16 of therapy in 10 healthy adults treated topically for eight hours per day.9 Five patients did have quantifiable (?10 ng/mL) amounts of imiquimod found in the urine, indicating some systemic exposure posttopical administration.

Literature Review

An open-label, uncontrolled study evaluated the efficacy of imiquimod therapy

for BCC in five OTRs. Inclusion criteria consisted of transplant recipients, a

primary BCC more than 8 mm in diameter, with a superficial, nodular or

infiltrative pathological pattern. Subjects were excluded if BCC was

recurring, morphoeiform, or located on the H of the face. A total of 10 BCCs

were diagnosed, of which histological pattern consisted of four superficial

(sBCC), three nodular (nBCC), and three infiltrative (iBCC).10

Study methodology included treatment with imiquimod application without

occlusion for eight hours per night, with a total of 24 applications in two

treatment arms. The first arm included treatment of five BCCs for four nights

per week for six weeks, and the second arm included treatment of five BCCs for

five nights per week for five weeks. Six weeks after completion of treatment,

a 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained to evaluate clearance. Absence of tumor was

observed in four of four sBCCs, two of three nBCCs, and one of two iBCCs. The

three tumors that did not respond to treatment were large and without erosion

at the end of treatment. No difference in healing rate was observed between

the two treatment arms. Of the 10 BCCs, seven showed erythema and six showed

erosions secondary to imiquimod therapy. Transplant rejection did not occur

within the eights months of treatment follow-up.10

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, right-left within-patient trial assessed the use of imiquimod in high-risk renal organ transplant recipients (rOTRs). High-risk rOTRs were defined as patients with fair skin, high previous sun exposure, and time since transplantation of five years or more. The primary objective assessed safety and efficacy of imiquimod treatment for viral warts, dysplasias, and AK. The secondary objective assessed the development rate of new SCC or carcinoma in situ (CIS) in imiquimod-treated skin compared with control during a one-year follow-up. Inclusion criteria consisted of adults 18–80 years, high-risk immunosuppressed rOTR, one or more biopsy confirmed as invasive SCC or CIS, two or more areas of equivalent bilateral involvement visually assessed on dorsal forearms or hands, and stable renal function (creatinine clearance not provided).11 A total of 21 patients were enrolled in a 2:1 (active/placebo) ratio. Imiquimod was applied eight hours per night, three nights per week, for 16 weeks. Upon study entry, two clinically similar areas were selected in each patient to serve as treatment and control areas. Twenty of the 21 patients completed 16 weeks of treatment. Of the 20 patients, 14 were in the active group and six were in the placebo group. Two patients died of unrelated causes (one from a spinal injury complication during month 10 of the follow-up phase and one of a brachial artery embolus during week 3 of treatment phase). Four patients were concurrently taking low-dose acitretin for chemoprophylaxis against further SCC, which failed to provide complete response in the one–four years before study entry.11 Imquimod treatment groups experienced a significant reduction in number of viral warts ( P = .05, n = 7), a nonsignificant reduction in number of dysplasias (P = .61, n = 5), and a nonsignificant reduction in the number of AKs (P= .61, n = 5). During follow-up, one patient developed two CIS lesions on imiquimod-treated skin and an invasive SCC on untreated control skin.11 Sixteen weeks of imiquimod treatment did not appear to affect renal function as none of the patients experienced an increase of more than 20% in serum creatinine (SrCr) concentration. This is consistent with traditional monitoring for acute renal graft rejection (abrupt rise of SrCr ? 30%). 12 Five patients developed clinically apparent inflammation (four active, one placebo), of which only one patient's symptoms were severe enough to necessitate a two-week discontinuation. Transplant rejection did not occur within the eight months of treatment follow up.11

An unblinded, uncontrolled pilot study of 12–16 weeks duration evaluated the safety and efficacy of imiquimod in the treatment of AKs in six OTRs. The size of the areas treated ranged from 40 to 100 cm 2. All subjects entered the study with stable immunosuppression for the previous six months and remained unchanged throughout the study. Treatment was applied for eight–10 hours per night, three nights per week, for 12–16 weeks. Mild erythema was evident in all areas treated two–three weeks after initiation. Total clearance of AK lesions was verified histologically in five of six patients. A 14-month follow-up revealed no recurrence of AK in imiquimod-treated areas. Only one patient demonstrated partial remission. 13 All patients experienced erythema, and two patients experienced erosions after six–eight weeks of treatment. No wound infection or scarring was observed in any of the treated areas. No systemic adverse effects or effects on systemic immunity were observed. Systemic immunity measurements included levels of creatine kinase, SrCr, C-reactive protein, proteinuria, liver function tests, bilirubin, hemoglobin, left ventricular ejection fraction, and lung function. All laboratory parameters remained stable during pretreatment, treatment, and follow-up phases (data not provided by authors). Transplant rejection did not occur within the 14 months of treatment follow-up. 13

An open-label, prospective, right-left within-patient study assessed the response of persistent, recalcitrant cutaneous warts to imiquimod in immunosuppressed individuals. Inclusion criteria consisted of eight or more clinically typical viral warts (VW) on the hands, forearms, or feet, which had been stable for 18 or more months, documented to be both persistent and refractory to standard treatment of 12 or more weeks of topical salicylic acid preparation and four or more cycles of cryotherapy. Fifteen patients were treated for 24 weeks and a follow-up was completed 18 months posttreatment. Thirteen of these 15 patients were OTRs (12 rOTR, one combined liver and renal transplant recipient [LOTR/rOTR]). Imiquimod was applied for at least eight hours per night, three nights per week, for eight weeks. If unresponsive, then the regimen was increased to daily application for another eight weeks. If still unresponsive, the regimen was applied daily under occlusion for an additional eight weeks.14 Twelve of the 15 patients completed treatment, of which 10 were OTRs. One rOTR was excluded prior to treatment because of abrupt spontaneous resolution. One rOTR patient withdrew because of lack of therapeutic effect at nine weeks, and another rOTR patient withdrew after eight weeks due to a 29% rise in creatinine level above baseline with warts unchanged. Both patients were included in the intention-to-treat analysis as treatment failures; therefore, the results consisted of 14 patients. All 10 of the OTRs required daily therapy with occlusion. Clearance of lesions began within eight weeks of treatment in three (two rOTRs and one LOTR/rOTR) of 14 patients. A 30% size reduction was documented in three rOTR patients. A nonstatistically significant correlation was observed among patients with a shorter duration of warts prior to study entry and a beneficial response to imiquimod therapy. 14 Local adverse effects occurred in four patients (one mild and limited erythema at treatment site, three pruritus, and transient superficial erosions). One of these patients had sufficient erosions and discomfort that resulted in discontinuation of treatment for one week. Three rOTRs experienced transient rises in SrCr (11%, 17%, and 29%). A renal biopsy in the patient with the 29% rise in SrCr revealed no evidence of rejection. Transplant rejection did not occur within the 18 months of treatment follow-up.14

A pilot study evaluated the efficacy of a combination of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and imiquimod, applied to SCC in situ , in five rOTRs. Inclusion criteria consisted of 1 or more biopsy proven SCC in situ on the lower extremities. All patients had at least one biopsy proven SCC in situ on the lower extremities and evidence of actinic damage. Areas of SCC in situ were treated with imiquimod three nights per week (M, W, F) and 5-FU applied four mornings per week (Sat, T, Th, Sun). Treatment duration lasted seven–nine weeks. A follow-up period of three–15 months revealed that none of the 5-FU/imiquimod-treated areas showed any evidence of recurrence. One patient developed a new SCC on untreated skin. All areas treated resulted in clinical and histological clearing. All lesions showed erythema and crusting within one week and resolved by week 5. Three patients exhibited increased peripheral edema on the lower extremities; these resolved by week 5. Laboratory monitoring parameters included CBC with differential, urinalysis, liver, and renal function tests, which were noted to have remained stable (data not provided by authors). Transplant rejection did not occur within the 15 months of treatment follow-up.15

Five studies evaluated the safety and efficacy of topical imiquimod administration in OTRs. Overall, the results from the reviewed studies suggest topical imiquimod therapy is both safe and effective as treatment of BCC, SCC, AK, dysplasia, and warts in immunosuppressed OTRs. Of the 52 OTRs who were administered topical imiquimod, no patient experienced an organ graft transplant rejection within the average follow-up period of 13 months. Ideally, long-term safety and efficacy studies that include measurements of TLR-7 activity and cytokine production would help assess pharmacological effects of topical imiquimod therapy in OTRs.

The Role of the Pharmacist

The pharmacist has a major role in educating immunosuppressed patients

regarding use of immunomodulator therapy, specifically imiquimod cream. Risk

factors for skin cancer and sun exposure prevention methods should be

discussed with all immunosuppressed OTRs. Patients should be informed that

imiquimod cream appears safe and efficacious for prevention and treatment of

skin lesions in OTR for up to 13 months of therapy. It is important to educate

patients to follow -up with physician appointments, especially to monitor

organ graft function.

All patients receiving imiquimod should receive instruction in proper application and removal. Patients should apply the cream during normal sleeping hours, rubbing it into the treatment area until it is no longer visible. The cream is typically left on the skin for approximately eight hours, then washed off with mild soap and water.2 The physician determines the frequency of application. Patients should also know about common adverse drug reactions, such as erythema and erosion, and that informed mild occurrence of these adverse events indicates a positive therapeutic response. Severe occurrence of erythema and/or erosion warrants informing the prescribing physician. As a pharmacist, it is difficult to differentiate between normal immune response and severe adverse reactions. Patients should be advised to follow up routinely with their prescribing physician, as severe adverse events may be resolved by a decrease in administration and/or duration of therapy.

References

1. International Transplant Skin Cancer Collaborative. www.itscc.org.

Accessed August 7, 2006.

2. Aldara package insert. St. Paul, MN, August 2005. Available at:

http://www.3m.com/us/healthcare/pharma/aldara/hcp_res_down.jhtml. Accessed

July 1, 2006: 3M Company.

3. Akira S, Takeda K, Kaisho T. Toll-like receptors: critical proteins linking

innate and acquired immunity. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:675-680.

4. Weeks CE, Gibson SJ. Induction of interferon and other cytokines by

imiquimod and its hydroxylated metabolite R-842 in human blood cells in vitro.

J Interferon Res. 1994;14(2 (Print)):81-85.

5. Testerman TL, Gerster JF, Imbertson LM, et al. Cytokine induction by the

immunomodulators imiquimod and S-27609. J Leukoc Biol. 1995;58:365-372.

6. Stanley MA. Imiquimod and the imidazoquinolones: mechanism of action and

therapeutic potential. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:571-577.

7. Hemmi H, Kaisho T, Takeuchi O, et al. Small anti-viral compounds activate

immune cells via the TLR7 MyD88-dependent signaling pathway. Nat Immunol.

2002;3:196-200.

8. Geisse J, Caro I, Lindholm J, Golitz L, Stampone P, Owens M, et al.

Imiquimod 5% cream for the treatment of superficial basal cell carcinoma:

results from two phase III, randomized, vehicle-controlled studies. J Am

Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:722-733.

9. Owens ML, Bridson WE, Smith SL, Myers JA, Fox TL, Wells TM. Percutaneous

penetration of Aldara(TM) cream, 5% during the topical treatment of

genital and perianal warts. Prim Care Update Ob Gyns. 1998;5:151.

10. Vidal D, Alomar A. Efficacy of imiquimod 5% cream for basal cell carcinoma

in transplant patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:237-239.

11. Brown VL, Atkins CL, Ghali L, Cerio R, Harwood CA, Proby CM. Safety and

efficacy of 5% imiquimod cream for the treatment of skin dysplasia in

high-risk renal transplant recipients: randomized, double-blind,

placebo-controlled trial. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:985-993.

12. Johnson H, Schonder K. Solid-Organ Transplantation. In: DiPiro J, Talbert

R, Yee G, Matzke G, Wells B, Posey L, eds. Pharmacotherapy: a

Pathophysiologic Approach. 6th ed: The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.;

2005:1613-1669.

13. Ulrich C, Busch J, Meyer T, et al. Successful treatment of actinic

keratosis with imiquimod cream 5%: a report of six cases. Br J Dermatol.

2001;144:1050-1053.

14. Harwood CA, Perrett CM, Brown VL, Leigh IM, McGregor JM, Proby CM.

Imiquimod cream 5% for recalcitrant cutaneous warts in immunosuppressed

individuals. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:122-129.

15. Smith KJ, Germain M, Skelton H. Squamous cell carcinoma in situ (Bowen's

disease) in renal transplant patients treated with 5% imiquimod and 5%

5-fluorouracil therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:561-564.

To comment on this article, contact editor@uspharmacist.com.