Osteoarthritis is a common

rheumatologic disorder. It is characterized by a gradual loss of cartilage

from the joints and, in some people, joint inflammation. Symptoms of

osteoarthritis include pain, stiffness, and loss of joint motion. It is

estimated that 40 million Americans of all ages are affected by osteoarthritis

and that 70% to 90% of Americans older than 75 have at least one joint

involved.1 In the United States, women are more often affected by

osteoarthritis, and older women are twice as likely to be affected by

osteoarthritis of the hands and knees than comparably aged men.2 As

the population of elderly patients continues to grow, osteoarthritis becomes a

significant medical and financial concern. With recent issues surrounding

NSAIDs and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors, managing osteoarthritis is now

more complex and individualized. This article briefly discusses the

background, prevalence, and diagnosis of osteoarthritis, then focuses on the

treatment options available for this disease.

PREVALENCE

The number of

osteoarthritis cases rises in people of advancing age, possibly beginning as

early as the third decade of life. The exact prevalence is unknown due to

uncertainties and variations in diagnostic definitions and reports of this

disease. In Western countries, radiographic change evident of osteoarthritis

is present in the majority of people by 65 years of age and in about 80% of

people older than 75.3 Notably, structural changes are not

necessarily associated with clinical symptoms of pain and inflammation. Many

patients with radiographic changes are asymptomatic, and those with symptoms

of osteoarthritis may not have evidence of radiographic changes of the

affected joint. Thus, an accurate diagnosis should consider the patient's

history, physical exam, and radiographic findings.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The

pathophysiology of osteoarthritis involves mechanical, biochemical, and

cellular processes. The common pathway is that all these processes change the

composition and properties of articular cartilage. Synovial fluid, along with

articular cartilage, permits almost frictionless movement of joint bones at

their points of contact. Healthy cartilage allows internal remodeling as

chondrocytes replace macromolecules lost in degradation. This process is

disrupted in osteoarthritis and is characterized by a progressive

deterioration of cartilage, resulting in the formation of osteophytes and loss

of cartilage.

Early changes to the joints

do not result in any symptoms, since there are no nerve fibers in articular

cartilage. Potential sources of pain in osteoarthritis include denuded bone,

microfractures of bone, stress to ligaments due to loss of cartilage,

low-grade synovitis, and spasms of surrounding muscles as the disease

progresses.

CAUSES AND CLINICAL FEATURES

The precise cause

of osteoarthritis is unknown. Multiple factors, such as heredity, trauma, and

obesity, interact to cause this disorder. Osteoarthritis is not a systemic

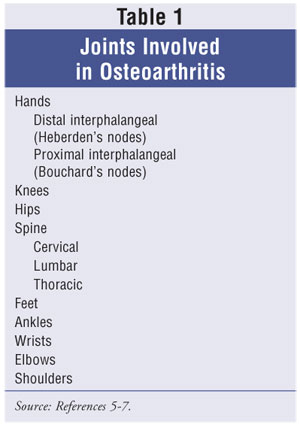

disease, and joint distribution often occurs in the knees, hands, and hips;

however, other joints can also be affected. Table 1 lists joints often

affected by osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis tends to develop slowly and

progresses over several years. The pain is often described as aching and is

felt in the areas surrounding the affected joint. Bony enlargements and

irregularities are typical, especially in the hands at the distal

interphalangeal joints (Heberden's nodes) and less commonly in the proximal

interphalangeal joints (Bouchard's nodes). Although these bony enlargements

are asymptomatic, many patients view them as part of a disabling arthritic

disorder or even an outward sign of aging. The clinical presentation of

osteoarthritis depends on the number of joints affected and the duration and

severity of the disease.

Patients with osteoarthritis of

the hip may complain of gait problems. After a period of inactivity, hip

stiffness is common and is usually a presenting factor. Patients with

osteoarthritis that affects the hands often have problems with manual

dexterity. This is evident when the first carpometacarpal joint is involved.

Instability or buckling of the knee is often noted in patients with knee

osteoarthritis. Some patients with erosive osteoarthritis may have signs of

inflammation in the interphalangeal joints of the hands. However,

osteoarthritis generally does not carry an inflammatory component, except in

severe, advanced disease.

Radiographic features and

laboratory findings are not definitive in the diagnosis of osteoarthritis.

Radiographic features of the disease show loss of joint space and presence of

new bone formation or osteophytes. However, absence of these radiographic

changes does not exclude a diagnosis of osteoarthritis. Analysis of synovial

fluid tends to reveal a white blood cell count of less than 2,000 per

millimeter.4

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis is

often made through physical examination and a detailed history of symptoms.

The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) has diagnostic criteria for

osteoarthritis at various sites, including the hip, knee, and hand.5-7

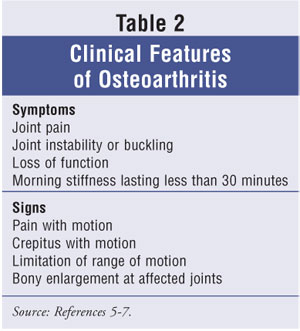

The usual presenting symptom is pain involving one or a few joints, but joint

involvement is usually asymmetric. Patients may complain of morning joint

stiffness that resolves within 30 minutes, which distinguishes osteoarthritis

from rheumatoid arthritis. As the disease progresses, joint stiffness can be

prolonged, and crepitus--a grating sensation in the joint--can occur. Crepitus

is caused by irregularities of the joint surfaces. Table 2 lists clinical

features of osteoarthritis.

TREATMENTS

The goals of

treatment for osteoarthritis are to control pain and swelling, minimize

disability, improve the quality of life, and educate patients about their role

in disease management. Treatment should be individualized to the patient's

level of function and activity, expectations, occupational needs, joints

involved, and disease severity, and to any coexisting medical problems.

Nonpharmacological Treatment

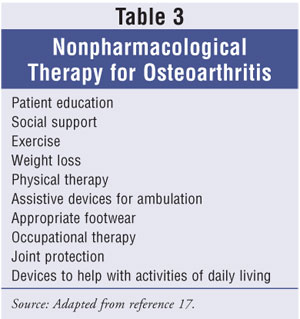

Nonpharmacologic

treatment, e.g., patient education, exercise programs, weight loss, assistive

devices, and alternative therapy supplements, appears to be the foundation for

management of this disease. Educational materials for patients to better

understand their diagnosis can be obtained from the Arthritis Foundation

(www.arthritis.org). Table 3 provides examples of nonpharmacological therapy

for osteoarthritis.

Patient Education: Education about the causes, effects, and symptoms of osteoarthritis, as well as a realistic understanding of what can be achieved with optimal therapy, is essential. Osteoarthritis has both physical and psychological effects. Its symptoms and limitations may cause feelings of frustration, dependency, and even depression. The more patients learn about the disease, the more they can participate in their own care. Social support can be achieved by building an informal support team or by participating in formal osteoarthritis groups.

Exercise

Programs: The goals of an exercise program are to maintain range of

motion, muscle strength, and general health. Patients with osteoarthritis are

often concerned that using a joint will "wear out" the already damaged area.

However, evidence shows that patients with osteoarthritic joints who

participated in regular low-impact exercise (e.g., biking and elliptical

machines) did not have an increased development of osteoarthritis.8

Patients should be encouraged to participate in aerobic exercises, such as

swimming or walking. Exercise can help combat the depression that may

accompany the chronic pain of osteoarthritis.9

Weight Loss:

Although obesity appears to be a greater risk factor for women, an association

exists between obesity and osteoarthritis of the knee in both genders.10

Weight loss has been shown to benefit patients with osteoarthritis.11

Symptoms associated with arthritis in the hips, knees, and feet are

exacerbated by obesity. Thus, primary prevention strategies should include

measures to achieve weight loss or avoid weight gain in overweight patients.

Assistive Devices:

A variety of appliances can help relieve osteoarthritis symptoms by

supporting the muscles linked to the affected joint. Examples of assistive

devices include crutches, walking aids, shoes inserts, splints, braces, and

special soles.11 Using special appliances may help patients feel

more comfortable, move around independently, and have improved function.

Physical and occupational therapy

may benefit patients with specific physical disabilities brought on by

osteoarthritis. Incorporating individualized exercise programs and teaching

patients how to manage activities of daily living may lead patients to feel

more independent and less affected by their disease.

Alternative Therapy

Supplements: Patients often seek alternative therapies for

osteoarthritis after experiencing side effects or incomplete relief of

symptoms from conventional medications. Since the herbal and supplement

industry is not regulated by the FDA, supplement composition can vary.

Glucosamine sulfate, a

popular treatment for osteoarthritis symptoms, is derived from oyster and crab

shells. No published studies have documented arthroscopic improvement in

arthritic cartilage with glucosamine use in humans. A meta-analysis concluded

that glucosamine may show efficacy over placebo in relieving painful symptoms.

12 Glucosamine is usually dosed at 1,500 mg per day in three divided

doses. Supplements should be taken for at least a month before improvement

occurs.

Chondroition sulfate has

demonstrated efficacy by acting as a building block of proteoglycan molecules

to improve the symptoms of osteoarthritis.13 Chondroitin is derived

mostly from shark and cow cartilage. Chondroitin is usually dosed at 1,200 mg

per day in three divided doses, and results may not be achieved for at least a

month.

Little evidence exists

showing that the combination of glucosamine and chondroitin is more effective

than either supplement alone.14 However, the use of the two

together is popular for the treatment of osteoarthritis. The

Glucosamine/Chondroitin Arthritis Intervention Trial (GAIT) was a six-month,

five-arm trial involving 1,500 osteoarthritis patients with mild to severe

pain. Patients were given glucosamine, chondroitin, glucosamine and

chondroitin combined, celecoxib, or placebo daily. The GAIT abstract posted on

the ACR Web site concludes that glucosamine and chondroitin together are

beneficial in treating moderate to severe knee pain due to osteoarthritis.

Results have yet to be presented.

S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe)

is a naturally occurring compound found in all living cells that is

commercially produced in yeast-cell cultures. Several studies have found SAMe

to be more effective than placebo in improving pain and stiffness related to

osteoarthritis.15,16 Dosages range from 400 to 1,200 mg per day.

Pharmacological Treatment

At present, there

are no specific pharmacologic therapies that can prevent the progression of

joint damage due to osteoarthritis. Because no medication has been shown to

cure this disease, patients should clearly understand the risks and benefits

of their treatment options. Pain relief is the primary indication for the use

of pharmacologic agents in patients with osteoarthritis who do not respond to

nonpharmacologic interventions. When quality of life becomes affected, it

would be appropriate to initiate pharmacotherapy to minimize disability and

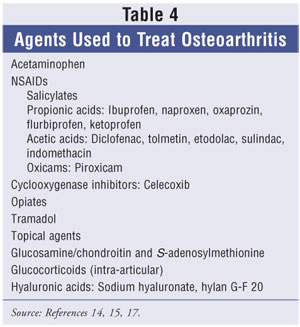

control pain. This article focuses on analgesics, NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors,

and intra-articular glucocorticoids and hyaluronate. Table 4 provides a list

of agents used to treat osteoarthritis.

Analgesics, NSAIDs, and COX-2

Inhibitors: The nonprescription analgesic acetaminophen, at doses of 1,000 mg

four times a day or 650 mg every four hours (up to a maximum of 4 g/day), is

the drug of choice for pain relief for noninflammatory osteoarthritis. The ACR

guidelines emphasize the use of acetaminophen as first-line treatment for

osteoarthritis of the knee and hip.17 This analgesic can

significantly improve function and decrease pain. Therapeutic doses of

acetaminophen produce minimum adverse effects, but hepatotoxicity can occur,

especially in patients who consume large quantities of alcohol.

NSAIDs are appropriate

choices for treating moderate or severe arthritis pain, as well as the

swelling, stiffness, and warmth of inflammation when present. NSAIDs carry a

risk of gastrointestinal (GI) toxicity, even at a low dose. GI complications

occur over the course of one year in about 2% to 4% of patients, and incidence

increases with age.9 Reduced prostaglandins in the gastric mucosa

from COX inhibition attributes to the GI side effects of NSAIDs. Proton pump

inhibitors may help control the GI symptoms associated with chronic NSAID use.

Misoprostol, a synthetic prostaglandin E1, can help prevent gastric

ulcers in patients on long-term NSAID therapy. Several risk factors appear to

increase the risk of NSAID-induced toxicity, especially in patients over age

65; patients with previous ulcer or upper GI bleeding; and patients taking

concomitant oral cortico steroids, anticoagulants, or multiple NSAID therapy.

18 The ACR guidelines recommend starting NSAIDs at low analgesic doses

and increasing to full anti-inflammatory doses only if the lower dose did not

provide adequate relief.17 The concurrent use of acetaminophen with

NSAIDs may allow the NSAID dosage to be reduced, thereby limiting toxicities.

COX-2 inhibitors may be

appropriate to initiate for patients with moderate to severe pain when non

selective COX inhibitors have proven ineffective or for those patients who

have a history of GI disease. COX-2 inhibitors have at least a 200- to

300-fold selectivity for inhibition of COX-2 over COX-1. Celecoxib is

recommended in doses of 200 mg per day for the treatment of osteoarthritis

pain. COX-2 inhibitors are associated with lower gastroduodenal toxicity, but

an increased risk of cardiovascular events has led to the withdrawal of two

previous agents (rofecoxib and valdecoxib) from the market. Although elderly

patients may choose to use celecoxib because of less GI effects, they need to

be made aware of the risks and benefits by their physician before beginning

treatment.

Treatment options for

osteoarthritis have been further complicated by the potential cardiovascular

risk associated with the use of naproxen and other NSAIDs. All NSAIDS, both

over-the-counter and prescription, and COX-2 inhibitors carry a warning

regarding cardiovascular and GI risks.19

Tramadol is usually given as

a rescue medication for symptomatic relief and can be considered an option if

NSAIDs fail. Use of this central-acting oral analgesic allows for a lower dose

of NSAIDs to be used. The recommended dose is 50 mg given every four to six

hours, with a total daily dose not exceeding 400 mg.9 Opioids can

be considered for patients with severe osteoarthritic pain that does not

respond to nonopioid analgesic agents. These agents are not recommended for

prolonged time periods because they cause constipation and increase the fall

risk, especially in the elderly.

Topical capsaicin, a

pepper-plant derivative, has been shown to relieve pain relating to

osteoarthritis better than placebo. Capsaicin cream 0.025% applied four times

a day was effective in managing pain caused by osteoarthritis of the knee,

ankle, wrist, and shoulder in a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial.

20 One common side effect is a localized burning sensation, and patients

should be advised to wash hands after application to avoid spreading to the

eyes or other mucous membranes. Capsaicin is available over the counter in

concentrations of 0.025%, 0.075%, and 0.25%.

Intra-Articular

Glucocorticoids and Hyaluronate: Patients who suffer from painful

flares of osteoarthritis in the knee may benefit from intra-articular

injections of corticosteroids, such as methylprednisolone or triamcinolone.

Short-term pain relief can be obtained with aspiration of the joint fluid,

followed by intra-articular injection of the corticosteroid when the joint is

painful and swollen. Injections should not be made in the joints more than

three or four times a year, to prevent potential cartilage damage from

repeated injections. Patients may have to consider surgical intervention if

they require more than three to four shots per year to control symptoms.

Hyaluronic acid provides

viscoelastic and lubricating properties to the joint. It is a major

nonstructural component of the synovial and cartilage matrix makeup. The

molecular weight and concentration of hyaluronic acid is thought to be

decreased in patients with osteoarthritis. The FDA has approved hylan G-F 20

and sodium hyaluronate injections for the treatment of pain caused by

osteoarthritis of the knee. The 2-mL dose is injected once weekly for three

and five weeks, respectively. The injections are well tolerated; however,

local skin reactions and pain with injection have been shown.

Intra-articular injections

must be administered using the aseptic technique, and the aspirated joint

fluid should be examined to rule out infections. Patients should minimize

activity and stress on the joint for several days following an intra-articular

injection.

Surgery

Osteoarthritis

often progresses to a degree where no cartilage remains and bone is rubbing on

bone. These patients who have symptoms that are not controlled with

pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic therapy and who have moderate to severe pain

and functional impairment may be candidates for orthopedic surgery. Depending

on the joint involved, some replacement procedures have become almost routine.

Patients should understand all the risks and benefits of orthopedic surgery

before making a decision.

Conclusion

Osteoarthritis is

a common, slowly progressive disorder that affects the body's joints.

Treatment of osteoarthritis should focus on the minimization of pain and loss

of function. An individualized approach is best for all aspects of the

disease, and the goals of the patient should be considered before selecting a

treatment plan. Nonpharmacologic therapy is the foundation of care for this

disease, and new therapies may become available to prevent further joint

progression in the future. It is important for providers to address with

compassion and understanding both the physical and emotional concerns these

patients may have.

REFERENCES

1. Oddis CV. New

perspectives on osteoarthritis. Am J Med. 1996;100:S10-S15.

2. Solomon L.

Clinical features in osteoarthritis. In: Kelly WN, Harris ED, eds. Textbook of

Rheumatology. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2001:1409-1418.

3. Lawrence RC,

Hochberg MC, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of selected arthritic and

musculoskeletal diseases in the United States. J Rheumatol. 1989;16:427-441.

4. Pelletier JP,

DiBattista, et al. Cytokines and inflammation in cartilage degradation. Rheum

Dis Clin North Am. 1993;19:545-568.

5. Altman R, Alarcon

G, et al. The American College of Rheumatology criteria for classification and

reporting of osteoarthritis of the hip. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34:505-514.

6. Altman R, Asch E,

et al. The American College of Rheumatology criteria for classification and

reporting of osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29:1039-1049.

7. Altman R, Alarcon

G, et al. The American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification

and reporting of osteoarthritis of the hand. Arthritis Rheum.

1990;33:1601-1610.

8. Lane NE. Exercise:

a cause of osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 1995;22:3-6.

9. DeAngelo NA,

Gordin V. Treatment of patients with arthritis-related pain. J Am Osteopath

Assoc. 2004;104:2-5.

10. Felson DT,

Anderson JJ, et al. Obesity and knee osteoarthritis. The Framingham Study. Ann

Intern Med. 1988;109:18-24.

11. Ravaud P.

Non-drug treatments for osteoarthritis. Presse Med. 2002;31:4S10-4S12.

12. McAlindon TE,

LaValley MP, et al. Glucosamine and chondroitin for treatment of

osteoarthritis: a systematic quality assessment and meta-analysis. JAMA.

2000;283:1469-1475.

13. Bourgeois P,

Chales G, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of chondroitin sulfate 1200 mg/day

vs chondroitin sulfate 3 x 400 mg/day vs placebo. Osteoarthritis Cartilage.

1998(supple A);6:25-30.

14. Kelly GS. The

role of glucosamine sulfate and chondroitin sulfate in the treatment of

degenerative joint disease. Altern Med Rev. 1998;3:27-39.

15. Di Padova C.

S-adenosylmethionine in the treatment of osteoarthritis: review of the

clinical studies. Am J Med. 1987;83:60-65.

16. Bradley JD,

Flusser D, et al. A randomized, double blind, placebo controlled trial of

intravenous loading with S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) followed by oral SAM

therapy in patients with knee osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:

905-911.

17. Recommendations

for the medical management of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: 2000 update.

American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Osteoarthritis Guidelines.

Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:1905-1915.

18. Lichtenstein DR,

Syngal S, Wolfe MM. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the

gastrointestinal tract: a double-edged sword. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:5-18.

19. Olsen NJ.

Tailoring arthritis therapy in the wake of the NSAID crisis. N Engl J Med.

2005;352:2578-2580.

20. Altman RD, Auen

A, Holmburg CE. Capsaicin cream 0.025% as monotherapy for osteoarthritis: a

double-blind study. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1994;23:S25-S33.

To comment on this article,

contact editor@uspharmacist.com.