|

|

|

|

|

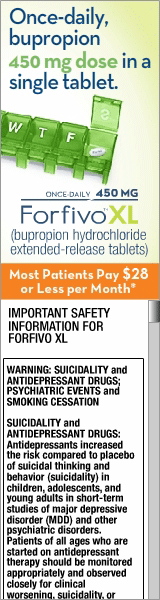

Advertisement

|

July 2, 2014

Study Finds Low Cardiac Risks With Antidepressant

Use in Pregnancy Boston—The risk of cardiac malformations in the first trimester is not substantially increased in pregnant women who use antidepressants, according to a large, population-based cohort study. Another study, however, raises questions of whether selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) use by expectant mothers may be predisposing unborn children to obesity and type 2 diabetes later in life. The first study, led by researchers from Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston, 2005, was partly prompted by FDA warnings in 2005 that early prenatal exposure to paroxetine may increase the risk of congenital cardiac malformations. That caution was based on epidemiological research, but subsequent studies came up with a variety of results. Some earlier research had raised the possibility of associations between paroxetine use and right ventricular outflow tract obstruction and between sertraline use and ventricular septal defects, according to background in the report. The most recent study, funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the National Institutes of Health, does not support the link, however, between antidepressants and cardiac anomalies, especially for paroxetine and sertraline. For the study from 2000 to 2007, researchers focused on 949,504 pregnant women who were enrolled in Medicaid during the period from 3 months before the last menstrual period through 1 month after delivery of their live-born infants. The risk of major cardiac defects among infants born to the 64,389 women (6.8%) using antidepressants during the first trimester was compared with the risk among infants born to women who did not use antidepressants. Results indicate that 6,403 infants who were not exposed to antidepressants were born with a cardiac defect (72.3 per 10,000), while 580 infants with exposure (90.1 per 10,000) had such defects. In addition, authors report no significant association between the use of paroxetine and right ventricular outflow tract obstruction (relative risk, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.59 to 1.93) or between the use of sertraline and ventricular septal defects (relative risk, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.76 to 1.41). Meanwhile, an animal study presented at the Endocrine Society’s recent ICE/ENDO 2014 meeting in Chicago suggested that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) use during pregnancy can increase the risk of obesity and diabetes in children. Study background notes that up to 20% of woman in the United States and 7% of Canadian women are prescribed an antidepressant during pregnancy. “Obesity and Type 2 diabetes in children is on the rise and there is the argument that it is related to lifestyle and availability of high calorie foods and reduced physical activity, but our study has found that maternal antidepressant use may also be a contributing factor to the obesity and diabetes epidemic,” said the study's senior investigator Alison Holloway, PhD, associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. “While it is known that these drugs can increase the risk of obesity in adults, it is unknown whether a woman’s antidepressant use during pregnancy increases the risk of metabolic disturbances in her children,” Holloway added. Using an animal model, Wistar rats, the study found that SSRIs resulted in increased fat accumulation and inflammation in the liver of the adult offspring, raising new concerns about the long-term metabolic complications in children born to women who take the antidepressants during pregnancy. Holloway pointed out that further studies in the area “may help in the identification of a high-risk group of children who may require specific interventions to prevent obesity and type 2 diabetes later in life.”

|

U.S. Pharmacist Social Connect

|

|