US Pharm. 2007;32(4):49-55.

Psoriasis is a common disease with an estimated worldwide prevalence of 2% to 3%. In the United States, 5.8 to 7.5 million people have this condition.1 It is a chronic, recurrent illness, which to date has no cure. Patients experience flares, which require repeated treatments with topical or systemic medications; therefore, pharmacists often have repeated opportunities to interact with patients who have this disorder. Psoriasis can have a negative impact on a patient's quality of life, affecting his or her self-esteem, work productivity, and personal relationships. Many patients develop psychological comorbidities such as depression.2-6 The pain and discomfort of the condition can be overwhelming, and patients are often self-conscious about disfigurement of the skin and nails, which is characteristic of the disease.5-7 Psoriasis can be a sensitive issue for many patients with this condition. This article will provide suggestions for pharmacists to consider when counseling patients who have this disorder.

OVERVIEW ON PSORIASIS

Psoriasis is an immune-mediated inflammatory papulosquamous skin disorder.

8 The activation of T-lymphocytes leads to the release of cytokines in

the body, which results in accelerated skin turnover. Patients with psoriasis

experience regeneration of the epidermis every two to four days, in contrast

to the 28-day cycle in patients with normal skin.9

Psoriasis is characterized by raised areas of inflamed skin, which appear red and glossy, with distinct, demarcated borders. The rash is covered by loose gray or silver-colored scales. Mechanical removal of the scales often results in the appearance of small droplets of blood on the skin (the Auspitz sign).8,9 Approximately 20% of patients will notice the development of lesions in non-affected areas of the skin after exposure to a trigger, irritant, or trauma at the site (the Koebner's Phenomenon).8,9 Areas of the skin that are affected by psoriasis are often referred to as psoriatic plaques or lesions.9

Psoriasis can also affect other areas of the body, such as the scalp, nails, and joints. Up to 50% of patients with psoriasis have scalp involvement. The scalp is often affected because it is susceptible to friction and trauma, and the hair filters ultraviolet light exposure. Often, the psoriatic plaque may be detected in the margin of the hair. Mild disease might resemble dandruff, while more progressive disease might appear similar to seborrheic dermatitis. Lesions may also appear in other hairy regions of the body, such as the groin. Patients might experience discomfort, itching, and hair loss in the affected areas.10 Hair loss can negatively affect a patient's quality of life.11

Approximately 11% (range, 6% to 39%) of patients with psoriasis develop a form of chronic inflammatory arthritis, called psoriatic arthritis, that affects the joints and connective tissue.1,8 Patients often develop redness, swelling, and warmth in the affected joint. It usually appears first in one (or just a few) joints and then involves more over time. Psoriatic arthritis can involve any joint in the body, including the spine. It can progress over time and result in joint deformity. Psoriatic arthritis can resemble other forms of arthritis, including rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis. It is associated with decreased range of motion, chronic discomfort and pain, chronic fatigue, and decreased quality of life.8

Psoriasis also affects the nails, with the fingernails being impacted more frequently than the toenails. The most common nail changes include surface pitting, thickening, discoloration, deformity, and separation of the nail from the nail bed.8,9,12,13 Nail changes are most common in patients who have psoriatic arthritis in the distal interphalangeal joint.8 The nail changes can be disfiguring, and patients are often self-conscious about these changes.

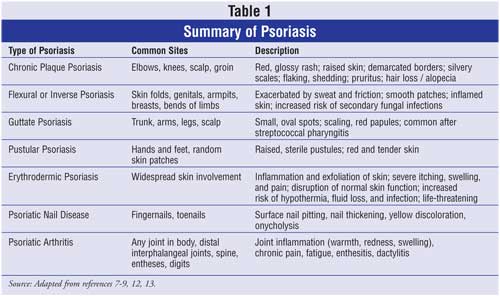

There are several different forms of psoriasis, and they have variations in clinical presentation (see Table 1). 8,9,12,13 Chronic plaque psoriasis is the most common type and accounts for 80% to 90% of the cases. In the clinical setting, psoriasis is staged based on the extent of skin involvement. Mild disease is defined as less than 3% of the body surface area (BSA) affected; moderate disease is 3% to 10% of BSA affected; and severe disease is greater than 10% of BSA affected.4

Psoriasis is associated with comorbidities such as obesity, diabetes mellitus, heart disease, Crohn's disease, depression, and anxiety.4,13

Psychosocial Aspects

The most important communication skills a health care provider should have

when talking with patients who have psoriasis are understanding and empathy.

Health care providers must be aware of the significant psychosocial challenges

their patients face on a day-to-day basis. Psoriasis is a chronic, recurrent

disease without a cure, so patients with this condition often experience a

significant reduction in their quality of life. The condition interferes with

physical, psychological, and social functioning.2-6 While the

condition is generally not life threatening, health care providers should

avoid comparing patients with psoriasis to other patients with "more serious

illnesses" as a strategy to "make them feel better." Doing so greatly

diminishes the impact of the disease on the patient's quality of life.

Verbally expressing understanding of their discomfort and embarrassment is

very important.

Physical Concerns: All patients experience chronic, noticeable flaking and shedding of the skin, with varying levels of discomfort that might be reported as moderate to severe depending on the extent and severity of the disease. In milder cases, patients may complain of redness, irritation, and itching, while in more severe cases, patients may experience significant pain, discomfort, soreness, bleeding, fatigue, and insomnia. Patients who develop arthritis might experience chronic pain, swollen joints, decreased range of motion, and decreased mobility, all of which can lead to deformity and disability.5,14

Due to these physical complications, patients' lives are often disrupted. The impact on physical functioning can be comparable to that experienced with other chronic health conditions, such as cancer, arthritis, heart disease, and diabetes.5,14 In patients with psoriasis-related chronic pain concomitant sleep disruption, the condition can be very difficult to tolerate. Moreover, as a result of chronic pain and fatigue, the patient's ability to cope with normal life problems becomes greatly diminished.

Psychiatric Concerns: Psychiatric comorbidities are common. Patients often report feeling self-conscious, embarrassed, frustrated, and helpless about their condition. This can lead to more intense feelings of anger, anxiety, and depression and to mood disorders, substance abuse, and suicidal ideation.5,14

Many patients become very self-conscious about their appearance. This is heightened when the psoriatic lesions appear in regions of the body that are hard to conceal, such as the hands, arms, face, and scalp (versus the umbilicus, back, chest). Some patients will wear seasonally inappropriate clothing in order to cover plaque on their arms, legs, and head. Often, this draws as much or more attention to their appearance as the psoriasis itself, which compounds the problem.3,5 In addition, patients who experience nail involvement can become embarrassed about the appearance of their hands and nails.7 Unfortunately, this can be very difficult, or even impossible, to conceal depending on the level of disfigurement.

Social Concerns: Many patients with psoriasis perceive a stigma associated with the disorder. Patients may become very anxious and concerned about others' reactions to their condition and may fear social rejection, often avoiding situations where this might occur. 3-5,14,15

Patients with psoriasis have reported that people avoid skin contact with them in social settings.3-5,15 For instance, someone might avoid shaking the patient's hand, even if the hand extended had no visible psoriatic plaque on it. Some patients with psoriasis have reported gross social rejection; they were asked to leave a social setting, such as a swimming pool, due to their psoriasis.5 It is important not to minimize this fear or embarrassment by saying things like, "Oh, it's not so bad…. Don't worry." Instead, say something like, "I can see how upsetting this is to you. Let's talk about what we can do to treat this."

Fear of embarrassment and rejection can lead to social withdrawal, deprivation of human touch, and mood disorders. It can impact work productivity, career advancement, and financial security. In people between the ages of 18 to 45, it can have a significant impact on socialization, occupation, and finances, because these are the ages when people traditionally establish their personal identity, develop relationships, choose a life partner, and establish a career.3-5,15

Psoriasis can also disrupt personal and intimate relationships. Sexual dysfunction has been reported in both females and males who have psoriasis. Physical pain and suffering can interfere with sexual desire. Psoriasis in the groin and genitals can cause pain and itching. People may feel sexually unattractive, and therefore might avoid intimate relationships. Depression, as well, can interfere with libido. Some psoriasis medications (such as methotrexate) can cause decreased libido and erectile dysfunction, which may compound the problem.16,17

Other Concerns: Some patients might feel overwhelmed with their medication regimen. Many psoriasis medications require repeated courses or chronic administration in order to control the condition. Some are messy, time-consuming, inconvenient, and odoriferous, which might interfere with patient adherence to the treatment plan. Other medications might have side effects that interfere with a patient's quality of life.13,14

COMMUNICATION CONSIDERATIONS

There is a common misconception among health care professionals and the lay

public that diseases of the skin are not as serious as other health problems

such as heart disease.2,5 Although psoriasis is not typically life

threatening, it can have a significant impact on a patient's life. Patients

with psoriasis can feel discounted and dismissed if they perceive that their

health care provider does not take their condition seriously. Therefore, it is

essential for pharmacists to not underestimate the impact of this condition on

their patient's life.5

Patients should be interviewed to ascertain exactly how psoriasis affects their lives. Pharmacists should avoid making generalizations or relying solely on clinical definitions of the disease. For instance, consider the following scenario:

Mrs. Smith is a 25-year-old female who reports to your pharmacy. She has chronic plaque psoriasis, which is isolated to her hands. According to the clinical classification system, this would be defined as mild psoriasis, since such a small BSA is impacted. However, due to the highly visible location of the disease, Mrs. Smith might be experiencing extreme embarrassment about the way her hands look. Your communication strategy should take into consideration her personal concerns.5

Inappropriate Response

Patient: I feel so self-conscious about how my hands look. They look so

terrible. My husband is afraid to hold my hand, because he's afraid of

catching this. Plus, he says my hands look gross.

Pharmacist: Oh, it's not so bad.

You tell him I said that he can't get this from you.

Patient: It's terrible to me.

Pharmacist: Mrs. Smith, it could

be so much worse. It's not life threatening and it's only on your hands.

Patient: (in disbelief) Only on

my hands? That's bad enough to me.

Pharmacist: Some patients have

this all over their body.

Patient: (sarcastically) That

makes me feel so much better. I have no right to complain. Please give me my

medicine.

Discussion: This pharmacist minimized the importance of this problem to Mrs. Smith. She is embarrassed and hurt, yet the pharmacist acknowledges none of this. While everything the pharmacist says may be true, it lacks caring and compassion.

Appropriate Response

Patient: I feel so self-conscious about how my hands look. They look so

terrible. My husband is afraid to hold my hand, because he's afraid of

catching this. Plus, he says my hands look gross.

Pharmacist: I can see how hurt

you feel. That must be difficult to feel rejected in that way.

Patient: It is awful.

Pharmacist: I see that. You can

tell your husband that he cannot get this from you. I know that doesn't make

you feel better, but he should know that.

Patient: I just want it to go

away.

Pharmacist: I know. I will give

you medicine, and we will talk about how to use it properly to get the most

benefit from it.

Patient: OK.

Discussion: This pharmacist acknowledged the patient's feelings of hurt and embarrassment. It is important to notice that the pharmacist did not take sides; she simply empathized with the patient, provided some useful information for the husband, and responded to the patient's desire to eradicate the problem by providing her with a treatment plan.

In addition to showing empathy and understanding, pharmacists should watch closely for any signs or symptoms of depression. For more information on communicating with patients who might be depressed, see reference 18.

CONCLUSIONS

It is important for pharmacists to be sensitive to the needs and concerns of

patients, to learn how a particular condition uniquely affects patients, and

to respond with understanding. Having someone who understands their feelings

without judgment provides patients with hope. This is especially important

with conditions like psoriasis.

References

1. About psoriasis statistics. National Psoriasis Foundation. Portland,

Oregon. Available at:

www.psoriasis.org/about/stats/?PHPSESSID=e5765ca00b1d62443e04843c56ab3a1c.

Accessed February 12, 2007.

2. Bhosle MJ, Kulkarni A, Feldman SR, Balkrishnan R. Quality of life in

patients with psoriasis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:35.

3. Barankin B, DeKoven J. Psychosocial effect of common skin diseases. Can

Fam Physician. 2002;48:712-716.

4. Kimball AB, Jacobson C, Weiss S, et al. The psychosocial burden of

psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:383-392.

5. Choi J, Koo JY. Quality of life issues in psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol

. 2003;49:S57-S61.

6. Russo PA, Ilchef R, Cooper AJ. Psychiatric morbidity in psoriasis: a

review. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45:155-159.

7. Williamson L, Dalbeth N, Dockerty JL, et al. Extended report: nail disease

in psoriatic arthritis--clinically important, potentially treatable and often

overlooked. Rheumatology. 2004;43:790-794.

8. Myers WA, Gottlieb AB, Mease P. Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis:

clinical features and disease mechanisms. Clin Dermatol.

2006;24:438-447.

9. Lebwohl ML. Psoriasis. American Academy of Dermatology: Information for

Dermatology Professionals. Available at:

www.aad.org/professionals/Residents/MedStudCoreCurr/DCPsoriasis.htm. Accessed

February 14 2007.

10. Elewski BE. Clinical diagnosis of common scalp disorders. J Investig

Dermatol Symp Proc. 2005;10:190-193.

11. Williamson D, Gonzalez M, Finlay AY. The effect of hair loss on quality of

life. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:137-139.

12. Luba KM, Stulberg DL. Chronic plaque psoriasis. Am Fam Physician.

2006;73:636-644.

13. Smith CH, Barker JN. Psoriasis and its management. BMJ.

2006;333:380-384.

14. Mease PJ, Menter MA. Quality of life issues in psoriasis and psoriatic

arthritis: outcome measures and therapies from a dermatological perspective.

J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:685-704.

15. Richards HL, Fortune DG, Griffiths CEM, Main CJ. The contribution of

perceptions of stigmatization to disability in patients with psoriasis. J

Psychosom Res. 2001;50:11-15.

16. Turel Ermertcan A, Temeltas G, Deveci A, et al. Sexual dysfunction in

patients with psoriasis. J Dermatol. 2006: 33:772-778.

17. Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Psoriasis and sex: a study of moderately to severely

affected patients. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:259-262.

18. Lloyd KB, Berger B. Communication concerning sensitive issues: the

depressed patient. USPharm. 2006;11:62-68.

To comment on this article, contact editor@uspharmacist.com.