US Pharm.

2006;31(9):39-48.

Each

year, nearly 2% of U.S. women of repro ductive age have an induced

abortion.1 This sobering statistic reminds all health care

professionals that too often, our patients at risk for unintended pregnancy

either fail to use effective birth control or use effective methods

incorrectly. With the goal of helping pharmacists facilitate contraceptive

success for their patients, this review provides an update regarding hormonal

and intrauterine contraceptives and details newer methods, including the

progestin-releasing intrauterine system, the contraceptive patch and ring, and

extended-regimen oral contraceptives as well as emergency oral contraception.

Combined Hormone

Contraceptives

Developed more than

four decades ago and representing one of the best-studied prescription

medications, oral contraceptives (OCs) combining estrogen and progestin

continue to be the most popular reversible contraceptive used by women in the

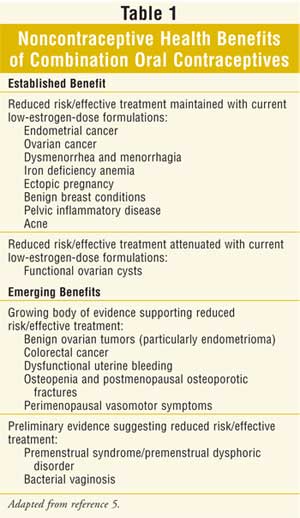

U.S.2 OC use is safe for most women and is associated with numerous

noncontraceptive benefits (Table 1). Although OCs represent a highly

effective birth control method when they are used correctly, inconsistent or

incorrect use (e.g., skipping as few as two to three consecutive days of use)

accounts for a surprisingly high annual failure rate of 8%.3,4 This

high failure rate underscores the clinical value of hormonal and intrauterine

contraceptives that do not require the users' daily attention.

Although the "pill" is not

new, many new approaches to initiating and taking OC tablets have recently

been developed. An innovative "quick start" approach to OC initiation involves

in-office ingestion of the first OC tablet immediately after a negative

pregnancy test, regardless of the patient's menstrual status. With this

method, patients have immediate exposure to combined hormonal contraceptives

(CHCs) and do not need to wait for their next menstrual period to begin or a

"Sunday start." A pilot study has suggested that this approach to OC

initiation is safe and results in higher rates of OC use than do conventional

pill initiation strategies. Patients who use the quick-start approach initiate

OC using an in-office sample pack but must fill their OC prescription in a

timely manner to ensure continued efficacy.5

The vast majority of

traditional OC regimens have used a 28-day plan with 21 days of combined

active pills followed by a seven-day hormone-free interval (HFI). A seven-day

HFI results in clearance of exogenous estrogen and progestin two to three days

after completion of active pills. This allows for several hormone-free days

during which levels of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating

hormone (FSH) rise and follicular growth occurs with increased risk of

ovulation if active pills are not started on time (referred to as escape

ovulation).6 Shortening the HFI or adding low-dose estrogen

during the usual placebo interval may decrease the risk of escape ovulation

and further improve contraceptive efficacy.7 Previously, the only

OC (Mircette) that attempted to shorten the HFI substituted low-dose estrogen

(10 mcg ethinyl estradiol) for five of the seven usual placebo pills.8

In recent years, the trend

toward reduction or elimination of the traditional seven-day HFI or placebo

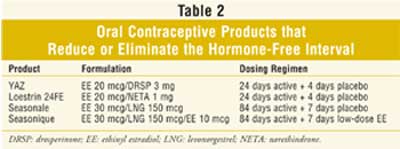

interval has resulted in the introduction of several new OC products (Table

2). Two new 28-day OC products, YAZ (3 mg drospirenone/20 mcg ethinyl

estradiol)and Loestrin 24 FE (1 mg norethindrone/20 mcg ethinyl estradiol),

were recently approved. Each provides 24, rather than 21, days of active

combined hormones, followed by four days of placebo tablets, thus shortening

the HFI.

The drosperinone-containing

product (YAZ) has also been evaluated in women with premenstrual dysphoric

disorder who desire pregnancy prevention. Response, defined as a 50%

improvement in daily mood and in physical and behavioral scores, was reported

in significantly more patients who received treatment in a placebo-controlled

study.9 Yet another OC product under development administers

combined OCs continuously without a pill-free interval for one year.

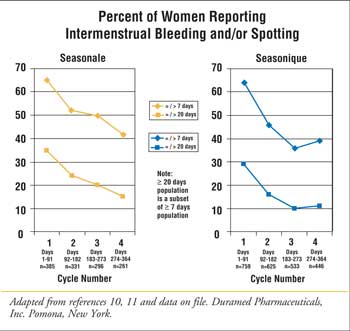

Extended OC regimens, which

reduce the number of withdrawal bleeding episodes per year, have also become

available and continue to increase in popularity. The first approved product

to use this approach was Seasonale (levonorgestrel 150 mcg/ethinyl estradiol

30 mcg), which extended active combined OC use to 84 days (12 weeks), followed

by one hormone-free week.10 Women interested in this "four periods

a year" approach to OCs need to be aware that breakthrough bleeding and

spotting (BTB/S) is more common during the initial active pill intervals than

that seen with conventional 28-day regimens. However, over time, unscheduled

BTB/S declines substantially.10

In May 2006, a 91-day-regimen

OC, Seasonique, was approved. This regimen is the first to completely

eliminate the HFI by utilizing seven days of low-dose estrogen (10 mcg ethinyl

estradiol) during the pill-free interval.11 While not evaluated in

head-to-head studies, bleeding data from clinical trials of the 91-day

regimens with and without low-dose estrogen during the HFI have been

subjectively compared (Figure 1).10,11 In each of the

studies, the incidence of BTB/S was similar in the initial cycle, as would be

expected given the use of equivalent formulations (levonorgestrel 150

mcg/ethinyl estradiol 30 mcg) during days 1 to 84. While the percentage of

patients reporting BTB/S decreased, the decrease was greater in the patients

who used low-dose estrogen during the HFI. The data for Seasonique showed a

median of less than one day of bleeding per patient month in extended cycles 2

through 4.11

It should be noted that women

taking extended-regimen CHCs, regardless of formulation or duration of

extension, will have a greater annualized exposure to estrogen compared to

women administered 28-day regimens. To date, there have been no reports of

additional health risks associated with this exposure.

Approved for contraceptive use

in 1992, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA or Depo-Provera IM)

contraceptive injections provide reversible long-acting birth control that is

as effective as sterilization. In the 12 years since its introduction, DMPA

has been to a large degree responsible for declining rates of unintended

pregnancies and abortions among U.S. women, particularly teens.12

With more than three decades of experience with use abroad, an extensive and

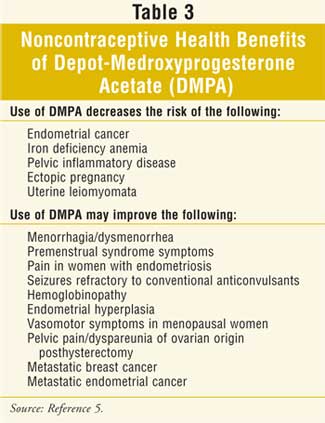

reassuring safety track record has accumulated for DMPA.12 In

addition, use of DMPA is associated with noncontraceptive health benefits (

Table 3). However, in late 2004, the FDA added a black box warning to

DMPA's package labeling regarding loss of bone mineral density (BMD) in women

using the product. Because use of DMPA suppresses ovarian estradiol

production, BMD declines during DMPA use. Fortunately, BMD is regained rapidly

after discontinuation of DMPA, and studies of BMD in women and adolescents who

had discontinued use of the product showed no BMD deficit compared to women

who have never used DMPA.5 DMPA use has not been linked to the

occurrence of osteoporosis or fractures. Accordingly (and notwithstanding the

black box), concerns regarding BMD should not limit prescription or

continuation of DMPA. Furthermore, ordering dual x-ray absorptiometry testing

in healthy young women receiving DMPA is not appropriate.13 When

DMPA is being used or considered in women with specific risk factors for low

BMD (e.g., slender athletes, perimenopausal smokers), use of supplemental

estrogen (e.g., oral conjugates equine estrogen 0.625 mg daily or equivalent

doses of other oral/transdermal estrogen) is appropriate.13

A new low-dose subcutaneous

formulation of DMPA, depo-subQprovera104 is now available.14

Medroxyprogesterone acetate injectable suspension (DMPA-SC) administered once

every three months provides a 30% lower total dose than traditional DMPA IM

(150-mg injection). In clinical studies, it suppressed ovulation for more than

13 weeks in all subjects regardless of body mass index, with no pregnancies

reported in more than 16,000 woman cycles of use.5,14 Although not

evaluated in a head-to-head study, the incidence of bleeding and amenorrhea

reported with DMPA-SC appeared to be similar to that reported with DMPA.

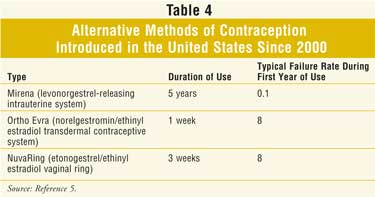

Since 2000, two alternative

estrogen-progestin CHC methods and one intrauterine contraceptive have been

introduced in the U.S. (Table 4). Approved in 2002, the contraceptive

patch, Ortho-Evra (transdermal norelgestromin/ethinyl estradiol patch), is

applied once weekly for three weeks; subsequently, withdrawal bleeding is

anticipated during a patch-free week. In a randomized clinical trial, the

contraceptive efficacy of the patch was comparable to that of oral

contraception.5 Application site reactions, breast discomfort, and

dysmenorrhea were each significantly more common in women treated with the

patch. This may, in part, be explained by a significantly higher overall

estrogen exposure.15 In a randomized, open-label pharmacokinetic

study, mean area under the time versus concentration curve 0–24 hours for the

patch was 1.6 times higher than reported for combination OC therapy containing

30 mcg ethinyl estradiol (p <0.05). Although this observation led to the FDA

adding a warning to the prescribing information for the contraceptive patch,

available published epidemiologic data indicates that the risk of venous

thromboembolism in users of the patch is similar to that in women using

combination OCs.16,17

Contraceptive efficacy with

the patch may be compromised in heavier women (>90 kg/198 lbs). In clinical

trials, women weighing at least 198 pounds had a statistically significantly

higher rate of pregnancy than the population of lower-weight women.16

Also introduced in the U.S. in

2002, NuvaRing (etonogestrel/ethinyl estradiol vaginal ring) is worn for three

weeks, followed by one ring-free week during which withdrawal bleeding occurs.

In comparative clinical trials, rates of breakthrough bleeding and spotting

were lower with the ring than with OCs.5 More than three quarters

of users indicated that they did not note discomfort related to the ring in

general or during sexual relations.

Studies have also been

conducted on extended use of Ortho Evra and Nuva Ring.18,19 In the

study of the patch, patients randomized to the 91-day cycle reported fewer

bleeding days but more spotting days during active therapy and significantly

longer menstrual cycles (6.9 days compared to 5.2 days; p <.001) than did

women in the 28-day–cycle group.18 In the vaginal ring

extended-regimen study, women randomized to the shorter extended regimen (49

days) experienced less bleeding and/or spotting than did women who received

the 91-day or 364-day regimens.19

Intrauterine Contraception

Widely used worldwide, intrauterine

devices (IUDs) offer women convenient, reversible birth control as effective

as surgical sterilization. In the mid-1970s, IUDs accounted for nearly 10% of

birth control methods use by U.S. women;5 however, today only 1% of

U.S. women use IUDs. This decline can be largely attributed to concerns among

clinicians and women regarding the link between IUDs and salpingitis and tubal

infertility; in particular, the morbidity and litigation associated with the

flawed Dalkon Shield has alarmed many people. A high-quality systematic review

found that if any increase in the risk of salpingitis is associated with IUD

use, it is small and appears confined to the first 20 days to one month

post-insertion and falls thereafter.20 Risk is also higher among

women with multiple sexual partners. Likewise, use of an IUD is not associated

with a subsequent increased risk of tubal infertility.20,21

Knowledge of these risks and their management may encourage clinicians to

recommend use of IUDs more broadly.

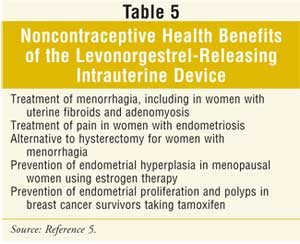

Two IUDs are currently

marketed in the US: Mirena (Table 5) and ParaGard. The copper IUD

(ParaGard), introduced in 1988 and approved for up to 10 years of use, is a

good choice for women who cannot or prefer not to use hormonal contraception.

Because use of the copper IUD can increase menstrual flow and cramps, it is

appropriate for women who have no excess menstrual flow or cramps at baseline.

In the fall of 2005, the FDA revised prescribing information for the copper

IUD.22 Nulliparous women (i.e., those who have never been

pregnant), as well as women with a history of pelvic inflammatory disease are

now considered appropriate candidates; however, women at current high risk for

sexually transmitted infection remain poor candidates. The IUD may be inserted

immediately post-partum or after the second month post-partum and is safe for

use during lactation.

The levonorgestrel-releasing

intrauterine system (IUS; Mirena), introduced in 2000 and approved for up to

five years of use, reduces menstrual flow and is therefore appropriate for

women who can use a progestin-based method and desire long-term contraception.

In addition to use as a contraceptive method, it has also been used in the

management of heavy menstrual bleeding and may be a more cost-effective

alternative to hysterectomy.23 However, women interested in using

the levonorgestrel-releasing IUS should be aware of that initial irregular

spotting or bleeding is common after insertion of this device. Hormonal side

effects, including acne and ovarian cysts, also occur in some users.

Noncontraceptive benefits associated with use of the levonorgestrel-releasing

IUS are detailed in Table 5.

Emergency Contraception

The use of

emergency (post-coital) contraception (EC) is estimated to have averted more

than 51,000 induced abortions in 2000.1 The only dedicated EC

formulation available in the U.S. is the progestin-only formulation (Plan B),

which consists of two levonorgestrel 0.75-mg tablets.

Progestin-only EC is more

effective and causes less nausea and emesis than combination EC.24

Prescribing information for Plan B indicates one tablet should be taken within

72 hours of unprotected intercourse, followed by a second tablet 12 hours

later.25 However, taking the two tablets together may be as

effective in preventing pregnancy as dividing the dose.24

Optimally, Plan B should be taken as soon as possible or within 72 hours of

unprotected intercourse; however, there is evidence that Plan B retains its

efficacy in pregnancy prevention when it is taken up to five days after

unprotected intercourse.24

In August, the FDA announced

that Plan B has been approved for OTC use in women ages 18 and older. The

product will remain available by prescription only for women ages 17 and

younger. Duramed, Plan B's manufacturer and a Barr subsidiary, has agreed to

provide consumers and health care professionals with labeling and education on

the product, as well as a hotline that provides answers to questions on Plan

B. Plan B will be available OTC only in locations staffed by licensed health

care professionals and stocked behind the counter, because it cannot be

dispensed without proof of age.

Pharmacists have a critical

role in providing access to EC, most importantly by maintaining an inventory

of Plan B. Pharmacists can provide women with information about the efficacy

and possible side effects of EC, as well as the need to obtain follow-up care

if menses do not occur as expected.

Use of Hormonal

Contraception and Risk of Breast Cancer

Since the July 2002

publication of findings from the Women's Health Initiative (WHI), which found

an increased breast cancer risk with use of menopausal combination hormone

therapy, concerns that use of combination hormonal contraception might also

increase this risk have been heightened. Many health care professionals are

not aware of the Women's CARE study, a large study sponsored by the CDC and

NIH that examined breast cancer risk associated with use of hormonal

contraceptives.26 Initial findings, published in August 2002,

indicated that regardless of length of OC therapy and age or family history,

use of OCs was not associated with an elevated breast cancer risk.5,26

A more recent publication from this same study found that neither use of DMPA

nor progestin-only implants is linked with an increase in breast cancer risk.

27

Conclusion

Given the number

and range of new contraceptive options, it is clear that birth control has

expanded well beyond the pill.5 Pharmacists knowledgeable about

older hormonal and intrauterine contraceptives and new longer-acting and

emergency contraceptives can have an important role by counseling their

patients and positively impacting public health by minimizing unintended

pregnancy and induced abortion.

Acknowledgement: The author acknowledges

the invaluable assistance of Kathryn M. Martin, PharmD, Ms. Georgette

Andreason, and Ms. Pam Neumann.

References

1. Jones RK, Darroch JE, Henshaw SK. Contraceptive use among U.S. women having

abortions in 2000-2001. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2002;34:294-303.

2. National Center for Health Statistics. Primary contraceptive methods among

women aged 15–44 years--United States, 2002. JAMA.

2005;293:2208.

3. Petitti DB. Combination

estrogen-progestin oral contraceptives. N Engl J Med.

2003;349:1443-1450.

4. Trussel J. Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception

. 2004;70:89-96.

5. Kaunitz AM. Beyond the pill: new data and options in hormonal and

intrauterine contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:998-1004.

6. Baerwald AR, Olatunbosun OA, Peirson RA. Ovarian follicular development is

initiated during the hormone-free interval of oral contraceptive use.

Contraception. 2004;70:371-377.

7. Mishell DR. Rationale for decreasing the number of days of the hormone-free

interval with use of low-dose oral contraceptive formulations. Contraception

. 2005;71:304-305.

8. Mircette Study Group. An open-label, multicenter, noncomparative safety and

efficacy study of Mircette, a low-dose estrogen-progestin-oral contraceptive.

Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:S2-S8.

9. Yonkers KA, Brown C, Pearlstein RB, et al. Efficacy of a new low-dose oral

contraceptive with

drosperinone in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Obstet Gynecol.

2005;105:492-501.

10. Anderson FD, Hait H. A multicenter, randomized study of an extended cycle

oral contraceptive. Contraception. 2003;68:89-96.

11. Anderson FD, Gibbons W, Portman D. Safety and efficacy of an extended

regimen oral contraceptive using continuous low-dose ethinyl estradiol.

Contraception. 2006;73:229-234.

12. Westhoff C. Depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate injection (Depo-Provera®); a

highly effective contraceptive option with proven long-term safety.

Contraception. 2003;68:75-87.

13. Kaunitz AM. Depo-Provera's black box: Time to reconsider? Editorial.

Contraception. 2005;72:165-167.

14. Jain J, Jakimiuk AJ, Bode FR, et al. Contraceptive efficacy and safety of

DMPA-SC. Contraception. 2004;70:269-275.

15. van den Heuvel MW, van Bragt AJM, Alnabawy AKM, Kaptein MCJ. Comparison of

ethinylestradiol pharmacokinetics in three hormonal contraceptive

formulations: the vaginal ring, the transdermal patch and an oral

contraceptive. Contraception. 2004;72:168-174.

16. Ortho Evra [prescribing information]. Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceuticals,

Raritan, NJ. Available at:

www.orthoevra.com/active/janus/en_US/assets/common/company/pi/orthoevra.pdf#zoom=100.

Accessed June 7, 2006.

17. Jick SS, Kaye JA, Russman S, Jick H. Risk of nonfatal venous

thromboembolism

in women using a

contraceptive transdermal patch and oral contraceptives containing

norgestimate and 35 microg of ethinyl estradiol. Contraception.

2006;73:223-238. Epub 2006 Jan 26.

18. Stewart FH, Kaunitz AM, Laguardia KD, et al. Extender use of transdermal

norelgestromin/ethinyl estradiol: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol.

2005;105:1389-1396.

19. Miller L, Verhoeven CH, Hout JL. Extended regimens of the contraceptive

vaginal ring: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:473-482.

20. Grimes DA. Intrauterine device and upper-genital-tract infection. Lancet

. 2000;356:1013-1019.

21. Hubacher D, Lara-Ricalde R, Taylor DJ, et al. Use of copper intrauterine

devices and the risk of infertility among nulligravid women. New Eng J Med

. 2001;345:561-567.

22. ParaGard T380A Intrauterine Copper Contraceptive [prescribing

information]. Duramed Pharmaceuticals, Woodcliff Lake, NJ. Available at:

www.paragard.com/paragard/custom_images/Prescribing-Info.pdf. Accessed June 8,

2006.

23. Lethaby AE, Cooke I, Rees M. Progesterone or progestogen-releasing

intrauterine systems for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst

Rev. 2005; 19(4):CD002126.

24.Westhoff C. Emergency Contraception. N Engl J Med 2003;

349:1830-1835.

25. Plan B [prescribing information]. Duramed Pharmaceuticals, Pomona, NY.

Available at: www.go2planb.com/PDF/PlanBPI.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2006.

26. Marchbanks PA, McDonald JA, et al. Oral contraceptives and the risk of

breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;346: 2025-2032.

27. Strom BL, Berlin JA, Weber AL, et al. Absence of an effect of injectable

and implantable progestin-only contraceptives on subsequent risk of breast

cancer. Contraception. 2004;69:353-360.

To comment on this article, contact

editor@uspharmacist.com.