US Pharm. 2006;7:16-22.

Croup causes substantial

morbidity, especially during flu seasons. The characteristic barking cough it

produces can be extremely troubling to parents, as they often think their

child is seriously ill. Fortunately, most cases of croup are mild and are

treatable with simple self-care measures such as vapor therapy.

Croup is a community-acquired

infection that results in inflammation of the larynx, bronchi, and trachea. In

children, it is usually sufficiently mild for outpatient treatment, but the

less common form seen in adults may require hospitalization.1,2

Croup occurs in as many as 6% of children ages 6 months to 6 years.3

Etiology

Croup may be due to

such bacteria as Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Corynebacterium diphtheriae,

or Streptococcus pneumoniae.1 However, viral invaders are

most often responsible for pediatric croup, also known as laryngotracheobronchitis.4

Parainfluenza causes more than 66% of cases, and the particular variant caused

by human parainfluenza virus 1 has the peculiar phenomenon of occurring since

1973 in odd-numbered years.1,2,4,5 Clinicians also observe a

clustering of croup cases corresponding to outbreaks of influenza A and B.1,4,5

Croup resulting from influenza A is less common but more severe than croup

arising from parainfluenza or respiratory syncytial virus.5 Other

viruses that may cause croup include metapneumovirus, adenovirus, rhinovirus,

enterovirus, measles virus, and herpes simplex virus.4 Patients

usually contract these viruses via the standard mechanisms by which

aerosolized viral illnesses are contracted (e.g., direct inhalation,

contamination of the hands followed by touching the mucosa of the eyes, nose,

or mouth).1 The incubation period is two to six days.4

Following inoculation, the progression of the viral invaders is to the nasal

mucosa and trachea. Airways are narrowed by inflammation of the larynx,

trachea, and bronchi, as well as by heightened production of mucus.

Epidemiology

Croup is most

common in children ages 6 months to 3 years, although it can be seen up to age

15 years and occasionally in adults.1,4,6,7 Viral croup is more

common in males, with a male–female ratio of 3:2.4,6 The peak

age for viral croup is 2 years.2 Most cases arise in the winter or

fall.6 If one member of a family has croup, the risk of passing it

to other members of the household is 15%.6

Manifestations of Croup

Patients undergo a

prodrome of two- to four-day duration in which they perceive the onset of a

respiratory infection in the upper airways, manifested by rhinorrhea, mild

cough, and low-grade fever.4 Eventually, release of inflammatory

factors causes erythema, exudate, and inflammation, culminating in symptoms

such as cough. The cough of croup is a harsh barking, resembling the sound

made by a seal.1,8 The cough may produce hoarseness from swelling

of the vocal cords.4,9 Swallowing is usually unaffected. Croup

often worsens at night, leading to many visits to emergency departments and

late-night calls to family physicians.8

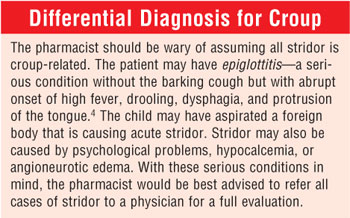

Croup is the most common cause

of nonchronic pediatric stridor.6 Stridor on inspiration coexisting

with coarse rhonchi is caused by a turbulent airflow arising from respiratory

obstruction.10 The patient may suffer shortness of breath,

tachycardia, or tachypnea.7 Nostrils may flare. Babies and young

children may exhibit supraclavicular, infraclavicular, intercostal, and

sternal retractions, where the chest and stomach muscles appear to suck in

with each breath.4,8 Rhinorrhea may also be present, but fever is

absent or mild. The child may be unable to rest normally.7 The lips

and fingernails may demonstrate the classic signs of anoxia as they begin to

show a blue tint.7

Medical examination of

patients with croup reveals a narrowing of the subglottic area with edema,

resulting in a radiologically identifiable abnormality known as the "steeple

sign."1 The child's airway is at its most narrow in the

subglottic area. For this reason, any inflammation or narrowing in this

location is highly likely to cause airway compromise.6

Croup seldom causes serious

sequelae.7 Only about 1.3% to 2.6% of patients require

hospitalization.4,9 The duration of croup is typically three to

five days.7 A mild cough may persist for several days after the

most serious symptoms have regressed. There is an association between a

history of croup and asthma, but it is unclear which is causal for the other.

In one study, a recent diagnosis of croup (within one year of the survey)

almost doubled the risk for asthma.11

Treatment of Croup

Many patients with

croup have mild cases that can be treated at home, but there are exceptions.7

Patients should be urged to see a physician if the child's lips and

fingernails are blue, if there is evident trouble breathing, if drooling or

trouble swallowing is present, if the child is restless or confused, or if

vapor therapy does not result in improvement.7 Patients with

cyanosis, extreme pallor, agitation, or decreased awareness of their

surroundings, or those who are becoming fatigued from the effort of breathing,

should be given supplemental oxygen immediately.10

Croup of bacterial origin

requires appropriate antibiotic therapy. If the patient has stridor at rest,

physicians often admit the patient to the hospital until the stridor has

halted.12 Steroid therapy is usually effective in reversing the

stridor, perhaps as soon as six hours after therapy is begun.12,13

Inhaled steroids are often used.9 Oral prednisolone in a dose of 1

mg/kg is often effective.12 In a randomized trial, investigators

discovered that a single dose of dexamethasone (0.6 mg/kg) was effective in

speeding resolution of mild croup in children.14 A Cochrane

analysis revealed that steroids reduce symptoms and readmissions to emergency

departments, shorten hospital stays, and reduce the need for treatment with

epinephrine.3

Most children with croup have

a mild case, and they appear to be normal in observable behaviors such as

hunger and thirst, they engage in play activities, and they display their

usual disposition.10 Standard treatment for most mild cases of

croup is inhaled vapor therapy to ensure that airway secretions retain

adequate hydration.5 One physician suggests that parents/caregivers

take the child into a steamy bathroom, as the moisture will improve the

condition.8 While conceding that the suggestion may not be fully

reference based, the physician asserts that steam "carries the weight of

decades of practice." Another suggestion is to place a clean, wet washcloth

over the nose and mouth, so each breath becomes humidified.7

Patients are often advised by

physicians to humidify the child's bedroom with a vaporizer or humidifier.

Pharmacies usually stock an array of humidification devices, ensuring that

patients can obtain a product that meets their needs.

Steam vaporizers are available

in several configurations. Electrode vaporizers require filling a reservoir to

the indicated point, followed by placement of a boiling chamber into the

reservoir. Steel or carbon electrodes within the boiling chamber are immersed

in the water when the boiling chamber is placed into the reservoir. When the

outlet is connected to electricity, elements normally found in water (e.g.,

calcium, magnesium, iron) serve to conduct the electricity between the

electrodes, heating the water. After a short period, the heated water exits

the vaporizer outlet as sterile steam. If the water is excessively soft, the

patient should add electrolyte to the water. Some companies advise salt, while

others advise baking soda. The purchaser should be encouraged to read the

product brochure in order to determine the recommended electrolyte and the

suggested amount to add. On the other hand, if the water already contains

excessive electrolyte, some vaporizers eject boiling water from the steam

outlet. In these cases, the consumer should be advised to dilute household

water with distilled water until boiling water is no longer ejected.

Other vaporizers function by

heating the water with a heating element. The amount of electrolyte is not an

issue in steam generation, since the heating element is not dependent on it.

Both types of vaporizers

produce heated mist that can alleviate croup. Because steam has the potential

to burn, all vaporizers should be placed at least 4 feet from patients. They

should also be placed away from household traffic flow, such as in a corner

away from doors. The patient may choose to use medication with a vaporizer.

Several brands are available, containing volatile oils that have been proven

safe and effective for cough through the FDA review process.

Patients may choose cool-mist

humidifiers to humidify their child's room. The traditional type has a

reservoir into which a rapidly rotating spindle is immersed. As the spindle

rotates, water in the reservoir is drawn upward onto a spinning disk, which

breaks it down into small droplets. The fan action of the disk disperses the

water into the room. Patients may also purchase ultrasonic humidifiers--devices

that use ultrasonic technology to create an ultrafine mist. Distilled water is

optimal for both types of humidifiers, as electrolyte in the water droplets

can produce an annoying white dust of calcium and other electrolytes on

surfaces. The white dust can interfere with electronic equipment (e.g.,

computers, VCRs) if the humidifier is allowed to run too close to them.

Croup is worsened by agitation

or crying.4 Thus, parents should be urged to make the child as

comfortable as possible under the circumstances.

Prevention of Croup

As croup is a

transmissible respiratory disease, prevention steps are those usually employed

in the prevention of similar conditions, like the common cold and influenza.7

People should wash their hands often, keeping fingers away from the nose and

mouth. Any potentially infected facial tissues should be handled as infectious

materials and should be discarded immediately and not handled by others. Toys

or other objects that have been mouthed by a child with croup should be washed

to eliminate pathogens. Visitors or relatives with cough should avoid holding

or playing with children in the home.

References

1. Nakayama JM,

Tokeshai J. A case report of adult croup: a new old problem.

2. Knutson D, Aring A. Viral croup. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:535-540.

3. Schooff M. Glucocorticoids for treatment of croup. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71:66-67.

4. Leung AK, Kellner JD, Johnson DW. Viral croup: a current perspective. J Pediatr Health Care. 2004;18:297-301.

5. Khater F, Moorman JP. Complications of influenza. South Med J. 2003;96:740-743.

6.

7. Information from your family doctor. What should I know about croup? Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:541-542.

8. Klass P. Croup--the bark is worse than the bite. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1283-1284.

9. Baines PB, Sarginson RE. Upper airway obstruction. Hosp Med. 2004;65:108-111.

10. Fitzgerald DA, Kilham HA. Croup: assessment and evidence-based management. Med J Aust. 2003;179:372-377.

11. Cagney M, MacIntyre CR, MacIntyre PB, Peat J. Childhood asthma diagnosis and use of asthma medication. Aust Fam Physician. 2005;34:193-196.

12. Parker R, Powell CV, Kelly AM. How long does stridor at rest persist in croup after the administration of oral prednisolone? Emerg Med Australas. 2004;16:135-138.

13. Hiramanek N. Answering a question about the treatment of croup. Aust Fam Physician. 2005;34:171.

14. Custer JR. A randomized trial of a single dose of oral dexamethasone for mild croup. J Pediatr. 2005;146:434-435.

To comment on this article, contact editor@uspharmacist.com