US Pharm. 2006;10:HS29-HS36.

Diverticular disease was first described in a

medical textbook in 1920. Before this time, diverticula in the colon were an

anatomical curiosity. Some observed that they were linked to perisigmoiditis,

peritonitis, and fistulas.1 Over the course of the 20th century,

the prevalence of diverticular disease in Western industrialized countries has

increased due to a rise in incidence, as well as an increase in awareness and

detection. Diverticular disease has had an important impact on health care

economics and utilization in the

Pathogenesis

Diverticulosis is an anatomic

diagnosis that indicates the presence of one or more diverticula. Acquired

diverticula form through the relative weakness in the muscular wall of the

colon, at the site where arteries known as the vasa recta penetrate the

muscularis layer to reach the mucosa and submucosa. Generally, diverticula are

multiple and have a diameter of 5 to 10 mm; however, some can measure up to 20

mm. They can occur in any location in the colon: ascending, transverse,

descending, and in the sigmoid portion.2 In contrast to a true

diverticulum, which includes mucosa and submucosa, muscle, and serosa, a false

diverticulum does not contain a layer of muscle in the bowel wall. Instead,

mucosa and submucosa herniate through the muscular layer. Diverticula are

covered only by serosa and tend to develop in areas where vasa recta penetrate

the bowel wall. These outpouchings are located mainly in the distal portion of

the colon. Involvement of the sigmoid colon occurs in up to 90% of patients.

The prerequisite lesion to diverticulitis is diverticulosis, the presence of diverticula in the colon, without inflammation. Diverticulitis occurs when a diverticulum becomes inflamed and infected. It is a disease experienced primarily by the elderly and becomes more common with age, with a prevalence of 65% by age 85.3 Diverticula are thought to occur as a result of increased luminal pressure in the colon, exacerbated by the deficiency of dietary fiber.4,5 While most cases of diverticulitis occur on the left side of the colon, right-sided diverticulitis is more common in younger patients, females, and Asian patients. The location of diverticulitis is important, since it has diagnostic, therapeutic, and prognostic significance.6

Although diet has not been formally studied in this disease, variations in incidence between countries with differing native diets suggest that diet may have a role. Vegetarians and others who consume large amounts of dietary fiber have a lower incidence of diverticula.2 Two studies have evaluated smoking and its relationship with diverticular disease, and the results are conflicting. The effect of alcohol has also been examined. In a Danish study, the risk of diverticulitis tripled in women and doubled in men who were alcoholics. However, this study appears to have some flaws:It did not have clear criteria for the diagnosis of diverticulitis and did not adjust for confounding factors, such as smoking and diet.7 Numerous studies consistently demonstrate that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications are associated with the complication of perforation of diverticular disease.1

Presentation

In Western countries, the most

common presenting complaint from diverticulitis is left lower quadrant

abdominal pain. The pain may be intermittent or constant and is typically

accompanied by a change in bowel habits (e.g., constipation or diarrhea).8

Other signs include nausea, vomiting, fever, chills, dysuria, or urinary

frequency.9 The severity of symptoms depends on the degree of

inflammation and presence or absence of complications. Physical examination

discloses left lower quadrant abdominal tenderness and may reveal abdominal

rebound or guarding if perforation accompanies the inflammation.3,10

A tender mass may be felt in the left lower quadrant. Patients with severe

diverticulitis and peritoneal signs can be hypotensive and appear quite ill.11

Detecting Diverticulitis

The approach to any patient with

abdominal pain should start with a thorough history and physical examination.

A complete blood count, complete metabolic profile, and urinalysis are usually

the next steps. In diverticulitis, leukocytosis with a predominance of

neutrophils is the abnormality often observed.11 The differential

diagnosis of acute diverticulitis includes acute appendicitis, irritable bowel

syndrome, Crohn's colitis, colon cancer, ischemic colitis, pseudomembranous

colitis, complicated peptic ulcer disease, and in females, ovarian cyst,

ovarian torsion, and ectopic pregnancy.

A variety of diagnostic tests can be useful in the evaluation of a patient with suspected diverticulitis. Ultrasonography is often the first imaging study in patients with vague abdominal pain. It can detect diverticulitis but may be limited by the ultrasonographer's ability to get adequate views in a patient with abdominal pain. Muscular hypertrophy, inflammation, and edema produce segmental hypoechoic bowel wall thickening. Ultrasound quite frequently detects right-sided diverticulitis, which may be a result of the higher incidence of diverticulitis in younger and female patients, in whom adequate images may be easier to obtain.6

Barium enema, a lower gastrointestinal exam, was once the test of choice. However, since many manifestations of diverticulitis are extraluminal, there tends to be a significant number of false-negatives using this test. Barium is contraindicated in the presence of localized peritonitis, due to its toxicity in the peritoneal cavity. Water-soluble contrast material is less toxic if there is perforation, but any enema increases the risk of perforation. Another limitation of contrast enemas is that they do not allow for grading of the inflammation or detecting the presence of an abscess.11 Abdominal x-rays appear normal in two thirds of all cases of diverticulitis. Lower endoscopy is universally abnormal, showing edema and inflammation. However, any inflammatory bowel condition may show these abnormalities. Therefore, this test lacks specificity. Colonic spasm during the endoscopy limits the ability to pass the endoscope, limiting the feasibility of performing the test as well.12

CT has emerged as the preferred test for patients with suspected diverticulitis. It can accurately diagnose diverticulitis and provides prognostic information useful for future treatment decisions.13-15 Another advantage of CT is that it can provide an alternative diagnosis when appropriate, aiding medical and surgical planning. CT has a high sensitivity and specificity for diverticulitis.16

Classification and Treatment

Treatment for diverticulitis is

based on age, location, severity, and presence of complications.

Diverticulitis can be broadly classified into complicated and uncomplicated

disease. Complications can be, but are not limited to, perforation,

obstruction, stricture, abscess, or fistula formation. Uncomplicated

diverticulosis requires no treatment. A diet high in fruit and vegetable fiber

can be recommended, if diverticulosis is incidentally found.17 The

location of diverticulitis is important, since right-sided diverticula are

solitary and congenital in origin. The right-sided form of the disease is

treated more conservatively, because abscess formation is rare.6

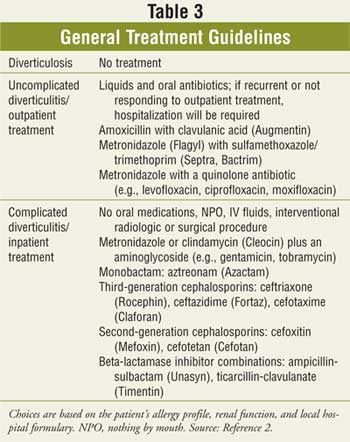

Outpatient treatment of uncomplicated diverticulitis is feasible. Patients who are immunosuppressed (e.g., the elderly or those taking chronic steroids or other immunosuppressants) are not suitable candidates for outpatient therapy. Appropriate candidates lack peritoneal signs, can tolerate oral intake, and do not experience systemic symptoms. These patients should be instructed to go to the emergency department if they experience fever, increased abdominal pain, or inability to tolerate enteral fluids.18

Broad-spectrum antibiotics with coverage against anaerobes and gram-negative rods should be instituted. Options for outpatient treatment include amoxicillin plus clavulanic acid, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim with metronidazole, or a quinolone with metronidazole. Symptoms should improve in two to three days, and antibiotics should be continued for seven to 10 days. Patients who do not improve should be hospitalized. After recovery from an initial episode, imaging with sigmoidoscopy and barium enema or colonoscopy should be performed to exclude the diagnosis of cancer. Studies show long-term fiber supplementation may prevent recurrence in more than 70% of patients after follow-up of more than five years.18

The hospitalized patient is usually given nothing by mouth and receives intravenous (IV) fluids, since feeding may increase pressure in the colon. Broad-spectrum antibiotics are appropriate therapeutic options. Some IV regimens include metronidazole with a quinolone or ampicillin, gentamicin and metronidazole, imipenem/cilastin, or piperacillin-tazobactam.17

Surgical Intervention

Once medical treatment fails, or

if a patient has acute perforation, obstruction, or an abscess greater than 5

cm in size, then surgery is necessary. Approximately 20% of patients with

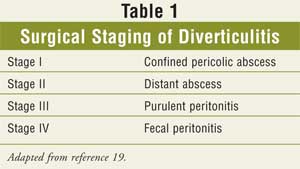

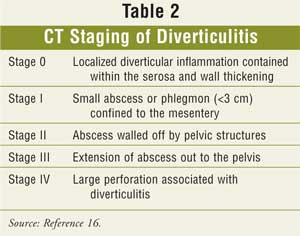

diverticulitis will require surgical treatment.5 A surgical staging

system defining the severity of diverticulitis, as well as a CT staging

system, are illustrated in Tables 1 and 2.

Three-stage surgery is no longer the treatment of choice; the two-step procedure is preferred. The first stage is a colostomy, and after a four- to 12-hour period of observation, a reanastomosis is then performed.20

While microperforations or phlegmon formation may

be managed with IV antibiotics, more robust abscess formation may occur,

resulting in the need for either interventional radiology or surgical

intervention.17 Abscesses occur in 16% of patients without

peritonitis.14

Fistulization may occur when an abscess extends to an adjacent organ. Colovesicular fistulas are the most frequently observed, followed by colovaginal; males are predisposed to the former, females to the latter.17 Acute obstruction may occur with diverticulitis due to luminal narrowing or compression secondary to abscess formation.17 This obstruction is rarely complete, which allows for bowel preparation prior to surgery. The main concern is carcinoma: Even with negative biopsies, resection is required if the appearance is suspicious. Resection with primary anastamosis is usually possible if there has been no perforation. Free intraperitoneal rupture of diverticulitis is an unusual complication and has a high mortality rate (20% to 30%). A two-stage surgical procedure is required in this case.22

Generally, surgery has been recommended after the first attack of complicated diverticulitis or two or more episodes of uncomplicated diverticulitis. Every case must be weighed based on its own merits, with the risks and benefits taken into consideration.17 Some experts recommend that any patients younger than 35 with diverticulitis of any type undergo elective sigmoid resection. However, this recommendation is controversial.5

Laparoscopically assisted anterior resection for diverticular disease has emerged as an important scientific advance, offering the possibility of quicker recovery time and shorter duration of hospitalization. There is a learning curve for laparoscopic surgery, but in experienced hands, the complication rate is lower and the recovery time is quicker than with open laparotomy. In a recent Australian study, the rate of conversion from laparoscopic to open procedure is about 8%.23

Conclusion

Due to its high prevalence and

possible complications, diverticulitis is a serious, potentially dangerous

disease. Among the primary symptoms, patients typically present with left

lower quadrant abdominal pain and fever, as well as gastrointestinal problems.

Early detection is important; CT has emerged as the preferred test for

patients with suspected diver ticulitis. Select patients with uncomplicated

disease can be managed with the use of oral antibiotics. Patients with

complicated disease, or those with uncomplicated disease who cannot be managed

on an outpatient basis, require broad-spectrum IV antibiotics (Table 3).

Percutaneous drainage and surgical intervention are necessary in some patients

with diverticulitis that is complicated by abscess formation. Laparoscopic

surgery is a new surgical approach in the management of this disease.

New therapies are continuously being investigated

to treat diverticulitis. As we learn more about this common disease, our

ability to maintain the health of our geriatric population improves. The

concept that this disease is primarily inflammatory has sparked interest in

the use of mesalamine and probiotics. Four different groups in

References

1. Morris CR, Harvey IM, et al.

Epidemiology of perforated colonic diverticular disease. Postgrad Med J.

2002;78:654-658.

2. Salzman H, Lillie D. Diverticular

disease: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:1229-1234.

3. Parks TG. Natural history of

diverticular disease of the colon. Clin Gastroenterol. 1975;4:53-69.

4. Floch MH, Bina I. The Natural

history of diverticulitis: fact and theory. J Clin Gastroenterol.

2004;38(5 suppl):S2-S7.

5. Ferzoco LB, Raptopoulos V, Silen

W. Acute diverticulitis. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1521.

6. O'Malley M, Wilson S. US of

gastrointestinal tract abnormalities with CT correlation. Radiographics.

2003;23:59-72.

7. Tonnesen H, Engholm G, Moller H.

Association between alcoholism and diverticulitis. Br J Surg

1999;86:1067-1068.

8. Ambrosetti P, Robert JH, Witzig J,

et al. Acute left colonic diverticulitis: a prospective analysis of 226

consecutive cases. Surgery. 1994;115:546-550.

9. Konvolinka CW. Acute

diverticulitis under age forty. Am J Surg. 1994;167:562-565.

10. Fischer MG, Farkas AM.

Diverticulitis of the cecum and ascending colon. Dis

11. Dominguez E, Sweeney J, Yong C.

Diagnosis and management of diverticulitis and appendicitis. Gastroenterol

Clin N Am. 2006;35:367-391.

12. Morris J, Stellato T, et al. The

utility of CT in colonic diverticulitis. Ann Surg. 1986;204:128-132.

13. Rao PM, Rhea JT, Novelline RA, et

al. Computed tomography in the evaluation of diverticulitis. Radiology.

1984;152:491.

14. Ambrosetti P, Robert J, Witzig

JA, et al. Prognostic factors from computed tomography in acute left colonic

diverticulitis. Br J Surg. 1992;79:117.

15. Ambrosetti P, Grossholz M, Becker

C, et al. Computed tomography in acute left colonic dicverticulitis. Br J

Surg. 1997;84:532.

16. Lawrimore T, Rhea JT. Computed

tomography evaluation of diverticulitis. J Intensive Care Med.

2004;19:194-204.

17.

18. Practice parameters for the

treatment of sigmoid diverticulitis-supporting documentation American Society

of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS). Available at: www.fascrs.org. Accessed

August 26, 2006.

19. Hinchey EF, Schaal PG, Richards

GK. Treatment of perforated diverticular disease of the colon. Adv Surg.

1978;12:85-109.

20. Floch M, White J. Management of

diverticular disease is changing. World J Gastroenterol.

2006;12:3225-3228.

21. Neff CC, Van Sonnenberg E, et al.

Diverticular abscesses: percutaneous drainage. Radiology. 1987:163:15.

22. Kriwanek S, Armbruster C, et al.

Prognositc factors for survival in colonic perforation. Int J Colorectal Dis.

1994;9:158.

23. Stevenson A, Stitz R, et al.

Laparoscopically assisted anterior resection for diverticular disease. Ann

Surg. 1998;227:335-342.

To comment on this article, contact editor@uspharmacist.com.