US

Pharm. 2006;2:28-33.

As community retail pharmacy

begins working with Medicare beneficiaries to implement the Part D

prescription drug benefit launched earlier this

year, new challenges for pharmacy are on the horizon. The Federal Deficit

Reduction Act of 2005 will change the way that Medicaid pays for generic

prescription medications on January 1, 2007.1 Other provisions of

the act take effect in the middle of 2006 and will result in greater pricing

transparency in the pharmaceutical market.

The legislation, which

narrowly passed the House of Representatives on December 19, 2005, and the

Senate on December 21, 2005, will reduce federal spending of many government

programs, including farm subsidies, student loans, and health care programs

such as Medicare and Medicaid, by about $40 billion over the next five years.

2 Most importantly for retail pharmacy, the legislation makes

significant reductions in Medicaid generic prescription drug payments, gives

states flexibility to impose higher premiums and cost-sharing amounts for

health care services, and allows states to offer slimmed-down health care

benefit packages to some Medicaid recipients.

Although hotly contested, the

bill's reductions in generic drug payments resulted from many key

policymakers' belief that Medicaid is overpaying pharmacies for

generic medications. During the past 18 months, several studies and reports

from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the Department of Health and Human

Services (HHS) Office of the Inspector General (OIG), and the Congressional

Governmental Accountability Office have led many key members of Congress to

conclude that Medicaid's average wholesale price (AWP)-based system for

reimbursing pharmacies for prescription drugs is flawed. In particular, the

studies showed that the system used by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid

Services (CMS) to set federal upper payment limits (FULs) for generic

prescription drugs often overstates a pharmacy's true acquisition costs for

generics and does not impose FULs in a timely manner when multiple-source

drugs are on the market. As a result, these studies concluded that Medicaid

had overpaid hundreds of millions of dollars to pharmacies for generic

medications.

Retail pharmacy has disagreed

with this assessment, arguing that the studies have exaggerated pharmacy

margins on generic prescriptions by calculating "percentage" margins rather

than "actual dollar" margins. This made it appear that pharmacies were making

significantly high margins on generics given the low-cost basis of these

drugs. The retail pharmacy industry has also pointed out that Medicaid

programs reap significant financial benefits when a pharmacy dispenses a

generic medication that costs about $20 on average, versus a single-source

brand name medication that costs about $100 on average. Thus, current

incentives to dispense generic medications would be sharply reduced if

payments to pharmacies significantly decreased. At the end of the day,

however, federal policymakers decided to take aim at generic drugs, reducing

payments for these medications by $6.3 billion in combined federal and state

Medicaid spending over the next five years.

Medicaid Payment Limits for

Generic Multiple-Source Drugs

Medicaid is an

important payer for most pharmacies, representing about 7% to 8% of the

average number of prescriptions filled by a typical pharmacy. Increased use of

generic drugs has been an important part of most states' Medicaid cost

management strategies. Generic medications represent about half of all

Medicaid prescriptions dispensed, and expenditures for these drugs accounted

for about 15% of the approximately $40 billion spent on prescription drugs by

Medicaid in 2005.

The new legislation will

change how CMS determines a generic drug's FUL, the maximum amount that the

agency will reimburse states for a specific dosage form and strength of a

generic drug dispensed by pharmacists--regardless of the cost of the product to

the pharmacy. Traditionally, FULs have been set for products that have three

or more sources of supply. CMS usually sets these FULs when, in addition to

the off-patent innovator, there are two additional A-rated generic versions of

the drug on the market.

Currently, the FUL is set at

150% of the lowest published price (i.e., wholesale acquisition cost [WAC],

AWP, or direct price) for a dosage form and strength of a generic drug

product. States cannot exceed the aggregate spending on drugs that have FULs

(i.e., they can exceed the FUL on one drug as long as they pay less on another

drug with an FUL). CMS generally reviews the pharmaceutical pricing compendia

(e.g., Red Book or Blue Book) to identify the lowest published price for a

generic drug. About 600 generic products currently have an FUL. Many states

further reduce the amounts that they pay for generics by placing "maximum

allowable costs" (MACs) on generic drugs, some of which already have FULs.

States use various methods to determine their MACs. Some states create MACs

for products that have only two sources of supply rather than three. All of

these policy approaches are permissible.

The new legislation would

calculate the FUL for generic drugs based on 250% of the lowest average

manufacturer's price (AMP) for the generic in the class, rather than 150% of

the lowest published price. CMS will identify the lowest AMP of a product in a

therapeutically equivalent and bioequivalent group of generics and multiply

that number by 2.5. This amount would be the FUL for all therapeutically

equivalent and bioequivalent generic drugs within that class, including the

innovator, unless the physician writes a restrictive prescription and wants

the Medicaid recipient to have the innovator drug. However, as is the case

now, states can further reduce these new generic payment limits through their

own MACs for generic drugs.

That raises the next question:

What is AMP? The term was defined in federal law under the Omnibus

Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990 as, the average price paid to

manufacturers by wholesalers for drugs distributed to the retail class of trade

. Manufacturers calculate AMP at the end of each calendar quarter to help them

determine the amount of rebates owed to state Medicaid programs for the

manufacturer's drug products dispensed in that quarter.

In theory, AMP should

represent the manufacturer's net revenue earned per unit (e.g., tablet,

capsule) for the sale of a drug to the manufacturer's retail pharmacy

customers only. When calculating AMP, manufacturers consider all of the

rebates, discounts, and price concessions that they provide to retail pharmacy

customers, such as prompt pay discounts, volume discounts, and cash discounts.

Manufacturers have to include the value of any free goods that they provide to

retail pharmacies when calculating the AMP.

Thus, AMP doesn't truly

represent the price that pharmacies pay for a drug; it represents the net

revenue earned by the manufacturer on the sales of that drug to the retail

class of trade. In addition, the AMP doesn't account for additional costs paid

by pharmacies for wholesaler charges or other distribution system charges to

stock and inventory the product in the pharmacy. As a result, AMP would have

to be increased by a certain percentage to reflect a pharmacy's true

acquisition costs. A recent OIG report found that on average, AMP was about 6

and 59 percentage points lower than WAC for brand-name and generic drugs,

respectively.3

To illustrate how AMP is

calculated and how it would be applied in determining the FUL, suppose a

manufacturer earned $100 in revenue from the sales of 1,000 units of a drug to

all of its retail pharmacy customers but paid $20 in discounts to these

customers. The AMP for this product would be 8 cents/unit ($100 minus

$20/1,000 units). If there are three manufacturers of a dosage form and

strength of a generic drug and the AMPs for these drugs are 8 cents, 10 cents,

and 12 cents, the new FUL would be 20 cents (2.5 X 8 cents/unit = 20 cents).

How will these generic payment

reductions affect retail pharmacy economics? Since AMP data are not public,

making estimates is difficult. However, some existing studies and reports shed

light on the economic impact of these reductions. This past summer, the OIG

estimated that if Medicaid based FUL amounts on 150% of the lowest reported

AMP, rather than 150% of the lowest published price, the program may have

saved up to $300 million in just one quarter of 2004. This figure represents

75% of the $396 million spent on generic versions of FUL drugs during that

period.

When these new generic drug

payment reductions go into effect in 2007, the average Medicaid generic

prescription reimbursement will decrease by approximately $4.25, which will

reduce the average generic payments to pharmacies by about 17%. The new

pricing system could therefore dramatically reduce retail pharmacy's

incentives to dispense generics, especially if the gross margin on generic

prescriptions is less than that of brand-name prescriptions.

Further, since the new

legislation changes the definition of a "multiple-source drug," an additional

number of generics will be subject to an FUL. CMS may begin setting an FUL

when only two therapeutically equivalent and bioequivalent generic drugs are

on the market. Currently, at least three such products have to be marketed

before a drug is considered a multiple-source product for the purposes of

determining an FUL. As a result, an FUL could be set on a product immediately

after the innovator's patent expiration when only the innovator and the first

generic are on the market. This is an important change. Many generics have a

six-month period of exclusivity during which no other generic can be marketed.

Even when three generic products became available, CMS did not always

immediately set an FUL on these products.

The use of an FUL for these

generics may have a significant impact on generic profitability and on overall

pharmacy profitability. A CBO study in 2004 found that pharmacies were earning

their highest dollar margins on "newer generics."4

These generics represented 8.4% of all prescriptions in 2002 but accounted for

37% of the increase in pharmacy margins between 1997 and 2002. This is because

during the time before an FUL is set, the generic drug is generally paid for

at the same AWP discount rate that the state uses to pay for a single-source

drug (e.g., AWP minus 14%). Under the new legislation, these generic drugs

will be subject to an FUL of 250% of the product with the lower AMP. In fact,

a significant amount of the savings may come from reductions in Medicaid

payments for generics with only two sources of supply.

Transparency in Pharmaceutical

Pricing

Many federal and

state policymakers have long maligned "AWP" as "Ain't What's Paid" and have

called for more accurate reimbursements through a greater transparency in the

actual prices paid by pharmacies for prescription medications. Under this

legislation, the Secretary of HHS is required to make the most recently

reported AMP data for patented single-source and multiple-source drugs

available to states on a monthly basis, beginning in July 2006. CMS has

previously been prohibited by law from making these data public. However, such

disclosure will create greater transparency in the pharmaceutical marketplace

and provide states with additional data to determine the reimbursement rates

to pharmacies.

Under the new legislation, the

Secretary of HHS is also authorized to establish a quarterly-updated Web site

that would provide the public with AMP data on medications. This will result

in increased price transparency as pharmacy benefits managers (PBMs) and plans

are able to use AMP to compare prices and set reimbursement rates. Customers

can also use public AMPs to compare the prices they pay for medications.

While the release of AMP data

may increase transparency, it is not clear that these AMP data will be

reliable or that they will reflect the prices paid by community retail

pharmacies. It has been well documented that there is no consistency in how

manufacturers calculate AMP. For example, some manufacturers include rebates

paid to PBMs and sales to mail-order and nursing home pharmacies when

calculating AMP. Such inconsistencies have resulted because CMS has never

given manufacturers final instructions on how to calculate AMP.

To address this situation, the

legislation requires that the OIG review the requirements for the AMP and the

manner in which it is determined based on the changes made under this

legislation. This OIG review must occur no later than June 1, 2006. The OIG is

instructed to make recommendations to the Secretary of HHS and Congress on any

appropriate changes to the way that AMP is determined. The Secretary must

publicize a regulation no later than July 1, 2007, that clarifies the

requirements for the AMP and the manner in which it is determined and that

takes into consideration the OIG recommendations. However, by this time, the

AMP data will have already been available to states and to the public for a

year, and there is no guarantee that the OIG or the HHS will issue a final

rule in 2007 requiring manufacturers to calculate the AMP using only the sales

to retail pharmacies.

When states and the public

obtain these new AMP data in mid-2007, it will most likely create more pricing

pressure on retail pharmacies. States will compare their current net payment

rates for single-source drugs with the reported AMP amounts for these drugs

and determine whether they are overpaying. Consumers will compare the prices

they are paying for medications at the pharmacies with the reported AMPs and

may also conclude that they are overpaying.

New Authority for States to

Impose Premiums and Cost-Sharing

With some

exceptions, states have generally been prohibited from charging premiums and

enrollment fees to Medicaid recipients.5 Unless they have obtained

a waiver, states have been able to impose only nominal cost-sharing fees on

Medicaid recipients--between 50 cents and $3, depending on the cost of the

service provided. These cost-sharing amounts have not been updated in a very

long time. Many state policymakers have complained that these low copay

amounts, combined with the ability of Medicaid recipients to obtain services

even if they are unable to pay, renders cost-sharing an ineffective means of

encouraging Medicaid recipients to use prescription medications that are more

cost-effective.

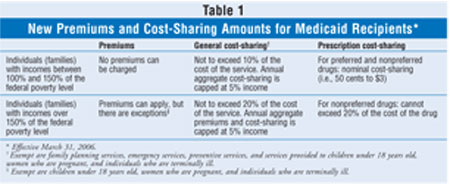

Beginning March 31, 2006, the

new legislation allows states to impose premiums on some Medicaid recipients

and to impose additional cost-sharing amounts on certain groups of Medicaid

recipients for Medicaid-covered services. States will be prohibited from

imposing premiums or enrollment fees on very poor Medicaid recipients (i.e.,

those with family incomes between 100% to 150% of the federal poverty level

[FPL]). However, states could impose a cost-sharing amount that does not

exceed 10% of the cost of the item or service. An aggregate maximum of 5% of

family income (either monthly or quarterly income, as specified by the state)

for all cost-sharing would apply.

For individuals with a family

income that exceeds 150% of the FPL, states could impose premiums and

terminate services after 60 days of nonpayment of premiums. In this income

group, states could impose cost-sharing amounts that do not exceed 20% of the

cost of the item or service. An aggregate maximum of 5% of family income

(either monthly or quarterly income, as specified by the state) for all

premium and cost-sharing amounts would apply. Populations exempt from these

new premiums include individuals younger than 18 years old, pregnant women,

and terminally ill patients in hospice care. Cost-sharing cannot be imposed on

these persons or on family planning, emergency, and preventive services.

Under the new legislation,

states may authorize providers to require payment of the cost-sharing amount

as a condition of providing the service. Providers may reduce or waive the

cost-sharing amount on a case-by-case basis. Under the current law, providers

cannot deny services to Medicaid recipients who cannot or will not pay

cost-sharing amounts. To keep pace with inflation, the Secretary of HHS would

be required, beginning in 2006, to index nominal cost-sharing amounts by the

annual percentage increase in the medical care component of the consumer price

index for all urban consumers (U.S. city average).

The legislation also creates

new cost-sharing policies for prescription drugs provided to Medicaid

recipients. Starting on or after March 31, 2006, states can designate certain

prescription drugs as "preferred" drugs, defined as drugs that are less costly

or the least costly drugs within a class. Other drugs would be designated as

"nonpreferred drugs." States can waive or charge Medicaid recipients lower

cost-sharing amounts for preferred drugs and higher cost-sharing amounts for

nonpreferred drugs.

The difference in the amount

of cost-sharing that can be charged for a nonpreferred drug compared to a

preferred drug depends on an individual's income level. For individuals with

an income below 150% of the FPL, the highest cost-sharing amount that can be

charged for nonpreferred drugs is equal to the nominal cost-sharing amounts in

existence at the time. For those individuals with an income above 150% of the

FPL, the maximum cost-sharing amount for a nonpreferred drug would be equal to

20% of the cost of the drug.

Individuals who are typically

exempt from Medicaid cost-sharing, such as children, may pay cost-sharing for

nonpreferred drugs. This amount cannot exceed the nominal cost-sharing

amounts. Cost-sharing amounts for preferred and nonpreferred drugs paid for by

an individual count toward meeting the aggregate overall 5% cost-sharing cap.

States must allow Medicaid recipients to use the nonpreferred drug at the

cost-sharing amount for the preferred drug if a physician determines that the

nonpreferred drug for the treatment of the same condition would not be

effective or would have adverse effects. These changes are summarized in table

1.

Conclusion

New changes to the

Medicaid program will have significant economic implications for community

retail pharmacy. The number of prescriptions paid for by Medicaid will

decrease with the shift of the dual-eligible beneficiaries from Medicaid to

Medicare Part D. Measures to encourage transparency for pharmaceutical pricing

have the potential to influence other larger government programs such as

Medicare Part D and third-party commercial payers.

The public release of AMP data

will allow consumers and third-party payers to compare the amounts they pay

for prescriptions with these data and create downward pressure on pricing.

Such a move will affect manufacturers, wholesalers, and retail pharmacies and

may reduce already thin margins in the retail pharmacy supply chain.

Pharmacies will compare the prices that they pay for medications to the posted

AMP and likely seek lower prices from manufacturers to reduce their

acquisition costs below the average. Will such increased transparency result

in greater uniformity in manufacturer pricing and a reduction or elimination

in multitiered manufacturer pricing? Only time will tell. One thing is

certain, though. Change is coming, and the retail pharmacy industry must be

prepared.

REFERENCES

1. House Report

109-362, H.R. 4241, S. 1932.

2. The House of

Representatives voted again to pass the bill 216-214 on February 1, 2006, as a

result of minor technical changes made by the Senate.

3. HHS-OIG. "Medicaid

Drug Price Comparisons: Average Manufacturer Price to Published Prices"

OEI-05-05-00240. June 2005.

4. Medicaid's

Reimbursements to Pharmacies for Prescription Drugs. Congressional Budget

Office. December 2004. Available at: www.cbo.gov/

ftpdocs/60xx/doc6038/12-16-Medicaid.pdf. Accessed January 12, 2006.

5. Under certain

circumstances, pregnant women and infants, and families with incomes greater

than 150% of the federal poverty level; individuals who are medically needy;

and workers with disabilities can be charged premiums, which have ranged from

$1 to $19.

To comment on this article,

contact

editor@uspharmacist.com.