US Pharm. 2006;10:103-108.

While it has been said that Alzheimer's disease was first identified in 1907 by Alois Alzheimer, one could argue that William Shakespeare certainly had a grasp on the decline of the elderly. In his play As You Like It, Shakespeare wrote the soliloquy "All the world's a stage," in which he describes the seven stages of man. His depiction of the last two stages is as follows: "With spectacles on nose and pouch on side;/His youthful hose, well saved, a world too wide/For his shrunk shank, and his big manly voice,/Turning again toward childish treble, pipes/And whistles in his sound. Last scene of all,/That ends this strange eventful history,/Is second childishness and mere oblivion,/Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything."

Alzheimer's disease is the most common type of dementia, affecting approximately 4.5 million Americans.1 Onset of the disease usually occurs after age 60, and risk increases with older age. About 5% of men and women ages 65 to 74 and nearly half of those 85 and older are affected by the disease. Memory loss is an initial symptom, and later signs include the inability to perform activities of daily living such as dressing, eating, and bathing; wandering; and change in mood and behavior. In the later stages, bladder and bowel incontinence may also develop. Alzheimer's disease affects not only the patient but also his or her primary caregiver.

Etiology

The cause of Alzheimer's disease

is unknown, although several factors are thought to have a role in the

disease. Possible causes include genetic dysfunction, accumulation of plaques

and tangles in the brain, and neurotransmitter and transmitter receptor

abnormalities that interfere with processes affecting cognition, memory,

socialization, and behavior.

No single gene is responsible for Alzheimer's disease--more than one gene mutation can cause the disease, and genes on multiple chromosomes may be involved. Early-onset Alzheimer's disease (before age 65) occurs in less than 5% of Alzheimer's disease cases and often runs in families. Many forms of early-onset Alzheimer's disease are caused by gene mutations on chromosomes 1, 14, or 21.

The amyloid precursor protein gene, found on chromosome 21, has been implicated in the accumulation of plaques in the brain. Buildup of amyloid beta 42 peptide leads to the formation of plaques. These plaques, as well as neurofibrillary tangles (twisted fragments of tau protein), lead to neuronal dysfunction and death. While most people with Alz heimer's disease have both plaques and tangles, some have only plaques, and others have only tangles.

Late-onset Alzheimer's disease (after age 65) has no known causes and is not associated with any obvious inheritance patterns. However, the apo li po protein E gene is thought to be a strong risk factor for this form of Alzheimer's disease. Evidence has shown that individuals with the ep silon 4 allele develop Alzheimer's disease earlier than those with the epsilon 2 or 3 alleles. However, having the epsilon 4 allele does not guarantee that a person will develop Alzheimer's disease. For example, some individuals with two copies of the epsilon 4 allele do not develop signs of Alzheimer's disease, while others without the epsilon 4 allele do.

Neurotransmitter and receptor deficits may also contribute to symptoms of Alzheimer's disease. One hypothesis is that the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor becomes overstimulated by glutamate, a naturally occurring excitatory neurotransmitter. Excessive stimulation of the NMDA receptor in patients with Alzheimer's disease can cause significant damage to the receptor.

Diagnosis

One deterrent to timely diagnosis

is the dismissal of symptoms as part of the normal aging process. The most

definitive method of diagnosis is autopsy; however, neuroimaging using

advanced technology, such as positron emission tomography, has proved to be a

sufficient--yet expensive--tool for confirming diagnosis. According to

DSM-IV diagnostic criteria, in order to receive an Alzheimer's disease

diagnosis, a patient must have memory loss as well as one of the following

symptoms:

• Aphasia

• Apraxia

• Agnosia

• Loss of executive functioning

• Inability to function in social or occupational settings.2

Physical ailments that might explain these symptoms should be ruled out. These include stroke; loss of vision, hearing, or other sensory functions; psychological disorders; and delirium. In addition, decline in function is usually gradual and continuous, with a significant change from baseline.

There are many psychological tests that can be used to measure the cog nitive function of patients with Alzheimer's disease. The Mini-Mental State Examination is a simple tool that can be administered in the clinic within 10 to 15 minutes. It includes 11 items evaluating memory, attention, recognition, and comprehension. The maximum score is 30, and the lower the score, the worse the patient's condition. Another test, the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive subscale (ADAS-Cog), includes 11 items evaluating memory, orientation, language, and praxis. The test requires one hour to administer, and patients can receive a maximum score of 70. The FDA recommends using the ADAS-Cog to measure efficacy in investigational drug trials. Other tests, such as the Clinician's Interview-Based Impression of Change and the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study–Clinical Global Impression of Change, can be used to assess patients' changes from one visit to the next. In addition, tests such as Functional Assessment Staging scale and the Global Deterioration Scale can provide further information on the behavioral and functional status of the patient.

Treatment

Treating Alzheimer's disease can

be challenging, specifically because the pathology of the disease is not fully

understood. At this time, preventing the onset of Alzheimer's disease is not

possible, since the exact mechanism of Alzheimer's disease is unknown. In

addition, only modest success has been achieved in reversing the condition

once it has developed. Therefore, one goal of treatment has been to retard the

progression of the disease. Another goal has been to reduce the impact of

symptoms on the caregiver (e.g., controlling outbursts of aggressive

behavior).

Successful treatments for Alzheimer's disease must be able to cross the blood-brain barrier in quantities sufficient to improve symptoms without causing untoward effects elsewhere in the body. Future therapies aimed at slowing the progression of the disease should strive to exceed the current average success rate of six months. In addition, Alzheimer's disease treatments should have a long enough half-life to allow infrequent dosing. Many patients with Alzheimer's disease need a caregiver, and these caregivers may have difficulty monitoring dosage due to other daily responsibilities.

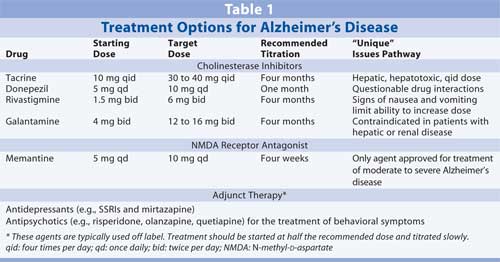

Treatment is most successful when started early in the course of the disease. Since onset of Alzheimer's disease is believed to occur much earlier than the time at which clinical symptoms are identifiable, it is im portant to educate the public about the early signs and symptoms of Alzheimer's disease--such as loss of memory, inability to navigate familiar places, confusion when performing simple tasks such as writing a check, reduced interest in intellectual pursuits, changes in grooming, and changes in sentence construction--so that treatment can begin as soon as possible. Several op tions for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease, as well as recommended dosages, can be found in Table 1.

Mild to Moderate Alzheimer's Disease: Cholinesterase inhibitors are the only drugs approved for the treatment of mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease; these include tacrine, donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine. Tacrine, donepezil, and rivastigmine are noncompetitive inhibitors of cholinesterase, while galantamine is a competitive agent. Competitive cholinesterase in hibitors may have an advantage, as they inhibit only where there are greater numbers of receptors.

Each of the approved cholinesterase inhibitors requires titration, at two- to four-week intervals, up to its respective recommended dose. However, because patients may still benefit from a less than optimal therapeutic dose, dosage is often based on the highest dose a patient can tolerate. The most prevalent side effects of these agents are nausea and vomiting, which may be accompanied by anorexia and weight loss. Thus, appetite and weight should be monitored closely.

Tacrine requires dosing four times per day. The initial dosage is 10 mg four times a day, titrated to 40 mg four times a day. Tacrine undergoes extensive metabolism and may be associated with hepatotoxicity. Use of this agent has dropped significantly with the introduction of the once-daily agent donepezil.

Treatment with donepezil usually begins with a dosage of 5 mg/day. After about one month of therapy, dosage can be increased to 10 mg/day. Donepezil is 100% bioavailable and the easiest cholinesterase inhibitor to use in terms of frequency and dose. It is also the most commonly used agent in clinical trials in conjunction with the NMDA receptor antagonist memantine.

Rivastigmine therapy should begin with a dose of 1.5 mg twice per day. Dosage should be doubled monthly, to the highest dose tolerated, but not to exceed 6 mg twice per day or the highest dose tolerated. In some clinical trials, treatment with higher doses of rivastigmine has resulted in a slight reversal of Alzheimer's disease symptoms in some patients. However, treatment with rivastigmine has been associated with nausea and vomiting, which limits the maximum tolerated dose in many patients. Rivastigmine is excreted renally, certainly a positive benefit for patients with liver disease. In a head-to-head trial with donepezil, rivastigmine showed no therapeutic advantage with regard to the amount of time patients spent in the highest dose range. In addition, both clinicians and caregivers found once-a-day dosing with donepezil easier.3

The starting dose of galantamine is 4 mg twice per day, titrated monthly to 12 mg twice per day. Since galantamine is a selective agent, some patients may tolerate treatment with this agent better. However, nausea is more common with galantamine therapy than with donepezil therapy. Galantamine is excreted equally through the kidneys and the liver.

Cholinesterase inhibitors lose efficacy after an average of six months. It is possible that the additional acetylcholine floods the neuron with transmitters to help the neuron function, and eventually, the neuron dies due to accumulation of plaques. This hypothesis is supported, in part, by the fact that all four of these agents are more efficacious in higher doses than in lower doses. Patients should continue treatment with these medications until there is no appreciable effect with regard to functional level.

Moderate to Severe Alzheimer's Disease: Memantine is the only FDA-approved agent for the treatment of moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease. This agent competes with glutamine for binding sites on the NMDA receptor, reducing the overall excitability of the neuron and preserving its function. Dosage starts at 5 mg/day and is titrated weekly by 5 mg until a 10-mg twice-a-day dose is achieved. Memantine is fairly well tolerated. It undergoes very little metabolism and is excreted mainly through the kidneys. In one study, patients taking memantine showed improvement in ability to carry out activities of daily living; they also performed better on the Severe Impairment Battery than those taking placebo.3 Differences between the treatment and placebo groups remained throughout the 28-week trial. Patients taking memantine demonstrated a degree of decline equal to that seen in the placebo group; however, a three-month delay in decline was seen in the treatment group. Patients taking cholinesterase inhibitors also experienced postponed decline, but the decline was more precipitous.

Treatment with both a cholinesterase inhibitor and an NMDA receptor antagonist has shown promising results. Improvement in the performance of everyday tasks (e.g., reading a map, dressing, or being able to prepare a meal), although slight, has been noted in trials using donepezil with memantine.4 Researchers have concluded that the addition of memantine in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease is beneficial.

Adjunct Treatment:In the early stages of Alzheimer's disease, loss of faculties can lead to depression and anger. Agents chosen for the treatment of depression in patients with Alzheimer's disease should be started at low doses and tritrated slowly. Mirtazapine is particularly well tolerated and has been shown to enhance appetite and promote sleep.

Antipsychotics are often used to control symptoms of sundown syndrome (early evening aggression and increased confusion) that are commonly present in advanced stages of Alzheimer's disease, despite FDA warnings about the increased risk of stroke in elderly patients taking these agents. In most cases, low doses of atypical antipsychotics are used. Antipsychotic treatment should begin with 0.25 mg risperidone at dinnertime or bedtime, 2.5 mg olanzapine in the evening, or 25 mg quetiapine in the early evening or at bedtime. These doses are tolerated well in the elderly and are often sufficient to control behavioral symptoms. If a higher dose is needed, most patients' symptoms can be controlled without adverse effects using no more than 1 mg risperidone, 5 mg olanzapine, or 50 mg quetiapine.5

Benzodiazepines are not recommended for use in elderly patients unless the benefits clearly outweigh the risks. Elderly patients tend to accumulate benzodiazepines due to decreased kidney function and are more susceptible to a paradoxical disinhibiting effect. Anticholinergic agents cause their own set of problems. Therefore, these classes of drugs are not considered first-line treatments for Alzheimer's disease unless the benefits outweigh the risks.

Nonpharmacologic Treatment:The benefits of maintaining quality of life and providing caregivers with rest have led to the development of day-care programs for patients with Alzheimer's disease or other types of dementia. Activity programs provide exercise and mentally stimulating activities geared toward patients' abilities. Some communities have Alzheimer's disease associations that provide such programs. Patients with Alzheimer's disease should be included in normal family and community activities as much as is safe for them; however, because they tend to wander or become incapable of finding their way back home, this may not always be feasible.

The Pharmacist's Role

It is important for pharmacists

to have patience when treating persons with Alzheimer's disease. Information

often needs to be repeated, and when possible, it should be written down for

caregivers and other assistants. In many cases, a spouse, adult child, or

hired aide will assume the role of full-time caregiver for a patient with

advanced disease. The pharmacist should ensure that the caregiver is present

for consultation and instruction, while maintaining respect for the patient.

Pharmacists can also provide caregivers with information about day programs and other services available in the community. Such programs not only benefit the patient but also provide the caregiver with rest and relief.

REFERENCES

1. National

Institute on Aging. Alzheimer's Information: General Information. Available

at: www.nia.nih.gov/Alzheimers/AlzheimersInformation/GeneralInfo. Accessed

September 12, 2006.

2. American Psychiatric

Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th

ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1994.

3. Wilkinson DG,

Passmore AP, Bullock R, et al. A multinational, randomised, 12-week,

comparative study of donepezil and rivastigmine in patients with mild to

moderate Alzheimer's disease. Int J Clin Practice.

2002;56:441-446.

4. Tariot P, Farlow MR,

Grossberg GT, et al. Memantine treatment in patients with moderate to severe

Alzheimer disease already receiving donepezil. JAMA. 2004;291:317-324.

5. Treatment of

agitation in older person with dementia. The Expert Consensus Panel for

Agitation in Dementia. Postgrad Med. 1998;spec no:1-88.

To comment on this article, contact editor@uspharmacist.com.