US Pharm.

2006;11:HS-44-HS-52.

A woman

in labor is commonly referred to as a parturient in the medical

literature. The parturient may be offered various medications to alleviate

labor pains. Medications given for analgesia in labor will decrease the pain

sensation, while medications used for anesthesia should provide complete pain

relief.1 Women of today, especially those living in the United

States, certainly have more options than their mothers and grandmothers did.

Stages of Labor

There are three

stages of labor. The first begins with the onset of labor, as a woman

experiences general abdominal cramping and uterine contractions. Once the

cervix has completely dilated, the second stage of labor begins. The woman

begins pushing during contractions, with the stage ending when the baby is

delivered. Pain in the second stage of labor may be more intense and

continuous. During the third stage, the placenta is delivered.2

Labor pain is affected by

nerves near the lower thoracic spinal segments (10-12) and the first lumbar

spinal segment. Medication administered into either the epidural or

subarachnoid spaces can block the pain.3

A woman's perception of labor

pain is affected by many factors, including cultural, psychosocial,

environmental, and physiologic influences. Nulliparous women may have more

pain in early labor, while women who have gone through childbirth previously

note more pain in the late first stage and second stage.

Early Use of Labor Analgesia

Early Chinese

documents describe the first use of an opioid, opium, in treating labor pain.4

Two British obstetricians pioneered the use of ether as an inhalational

anesthetic for labor pain in the 1840s. Chloroform eventually became the

anesthetic of choice in place of ether.5 In 1902, morphine and

scopol amine use for labor pain was reported. There was little benefit in

pain relief, although the "twilight sleep" caused maternal confusion and

forgetfulness of the event. However, these drugs were also associated with

neonatal respiratory depression.6 Meperidine came into use during

the early 1940s, eventually becoming the most regularly used opioid for labor

pain worldwide.7

The first reported case of

regional anesthesia used in labor occurred in 1900, when a physician from

Switzerland administered spinal cocaine to six of his patients. Two years

later, spinal anesthesia was used for the first time for a cesarean delivery

in the U.S.8 In the late 1960s, epidural analgesia became more

accepted, especially among academic health centers and private hospitals.

Nonpharmacologic

Interventions

There are multiple

nonpharmacologic techniques used to reduce labor pain. These interventions

include acupuncture, massage, intracutaneous sterile water blocks, water

immersion or hydrotherapy, music or audioanalgesia, cold or heat therapy,

hypnosis, breath ing/focusing, and transcutaneous electrical nerve

stimulation.9 However, a primary disadvantage of alternative or

nonpharmacologic techniques is the lack of rigorous research to support their

use. Advantages to nonpharmacologic interventions include their low cost and

wide availability and the fact that they pose low or no risk to the mother and

neonate and allow active participation of the mother throughout the labor

process.

Routes of Analgesia

Administration

There are several

routes of analgesia administration used to reduce labor pain. These routes

include intravenous (IV), intramuscular (IM), subcutaneous, paracervical

blocks, epidural, spinal, and combined spinal epidural.

Parenteral Routes:

Opioid derivatives are the agents used for IV and IM analgesia. These agents

may moderately reduce labor pains, but they cannot eradicate the pain. IV

administration provides a faster onset of analgesia with a shorter duration of

action, while IM administration should be considered when pain relief for a

longer duration is needed (see Table 1).1 Common side

effects of opioids include constipation, dry mouth, urinary retention,

sedation, nausea, vomiting, dysphoria, hypoventilation, pruritus, and neonatal

depression.1 Several studies have evaluated the benefits of IV

analgesia. Soontrapa et al. reported that fewer than 25% of those receiving an

IV opioid analgesic had adequate pain relief.10

Parenteral use of opioids may

be warranted in those patients who have contraindications to epidural

analgesia; previous spinal surgery or deformity, which may make it impossible

to place an epidural; or the unavailability of anesthesia or personnel

services.

Morphine was the first pure

opioid given for relief of labor pain. Doses ranged from 1 to 4 mg with a peak

effect at 20 minutes after IV administration. The peak effect for IM dosing

was delayed to one to two hours. Side effects with morphine include maternal

and neonatal respiratory depression and maternal nausea, vomiting, and

sedation. Morphine is rarely used during labor in the U.S. because of its long

half-life, high incidence of sedation, and neonatal side effects.11

In the 1940s, meperidine came

into use for labor analgesia and is now the most frequently used opioid for

labor pain. IV doses are typically 25 to 50 mg and IM doses are 50 to 100 mg.

It has a faster onset of action--five to 10 minutes for IV dosing and 45

minutes for IM dosing--than morphine does. As with morphine, meperidine can

cause neonatal respiratory depression. The significance of this effect depends

on the dose given, as well as the time between dose administration and

delivery. A neonate is less likely to suffer respiratory depression if

delivery occurs one hour after dosing or more than four hours after dosing.

The strongest effects on the neonate tend to occur if delivery takes place two

to three hours after the meperidine dose is given. Another disadvantage of

meperidine is its metabolism to normeperidine in the neonate, as this

metabolite has a much longer half-life (63 hours).11,12

Fentanyl, a synthetic opioid,

has several advantages over morphine and meperidine. It has a rapid onset of

action of only one to two minutes when it is given intravenously and a short

duration of action of 60 minutes. IM and IV doses range from 50 to 100 mcg.1,12

Fentanyl does not readily cross the placenta, as morphine and meperidine do;

however, neonatal respiratory depression may still occur. Fentanyl has been

noted to cause less maternal sedation, nausea, vomiting, and pruritus as

compared to morphine and meperidine.

Butorphanol, an opioid

agonist-antagonist, is given in doses of 1 to 2 mg IV or IM. It has an onset

of action of two to three minutes after IV dosing and 10 to 30 minutes after

IM dosing. It has a three- to four-hour duration of action with either IV or

IM administration.1,12 Another opioid agonist-antagonist is

nalbuphine, which can be given as either an IV or IM10-mg dose. It has a

slightly faster peak effect of two to three minutes when given intravenously

and 15 minutes after IM dosing.1,12 Both butorphanol and nalbuphine

may cause maternal respiratory depression.1 Patients who may take

narcotics for other medical conditions or who are drug abusers may experience

withdrawal symptoms due to the antagonistic effects of butorphanol and

nalbuphine.11

Paracervical Blocks: Paracervical block was a method commonly used in the 1940s and 1950s; however, its use has decreased with the increasing availability of epidural analgesia. A paracervical block involves the injection of local anesthetics, such as lidocaine or bupivacaine, into either side of the cervix. A major disadvantage seen with paracervical blocks is fetal bradycardia. When this procedure was first implemented, fetal bradycardia was reported to occur 70% of the time.13 However, this incidence has dropped to a rate of 15% with present methods.14

Regional Analgesia: Regional analgesia includes epidural, spinal, and combined spinal and epidural procedures that result in partial to complete loss of pain sensation below the T8 to T10 levels of the spine (see Table 2 for contraindications to regional anesthesia).12 In the U.S., there are four million births each year, and nearly 60% of women giving birth receive an epidural.15 Epidural procedures require administration of analgesics or anesthetics via catheter into the area of fibrous connective tissue (dura mater) covering the spinal cord. Spinal analgesia requires piercing the dura into the cerebrospinal fluid–filled cavity, where the spinal cord is located.11 Spinal analgesia is a single dose of a long-acting local anesthetic with or without an opioid agent. For spinal analgesia, small doses of medications are required (e.g., fentanyl 25 mcg with 1 mL bupivacaine 0.25%), whereas, larger doses are needed for epidural use (e.g., fentanyl 50 to 100 mcg with 10 to 15 mL bupivacaine 0.125% to 0.25%).3

Combined spinal and epidural

analgesia is a more recent technique that offers the benefit of spinal

analgesia's quick onset of action, along with the ability to provide an

epidural for an extended period. Combined spinal and epidural administration

is accomplished via a "needle-through-needle" technique. Medication is

injected via the spinal needle into the subarachnoid space. The spinal needle

is removed, leaving the epidural needle in position, and the epidural catheter

is threaded through.1 Within three to five minutes, analgesia

begins with a duration of 60 to 90 minutes. As the spinal analgesia fades, the

anesthesiologist can use the epidural catheter during the remainder of the

labor process.

Continuous infusion of an

anesthetic with an opioid is commonly used in labor. Continuous infusions

offer a more steady level of pain control, compared to bolus administrations.

These infusions typically contain bupivacaine or ropivacaine 0.04% to 0.125%

and fentanyl or sufentanil.3

Factors that affect rates of

epidural use include availability of anesthesia services, conditions or

criteria for use (e.g., stage of labor or patient demand), and the size of the

hospital.16 Currently, there is debate in the medical literature on

whether epidurals should be given early in labor rather than later and what

effects this may have on the labor process and delivery. In hospitals with

delivery rates of at least 1,500 births per year, the percentage of patients

getting epidurals jumped from 22% to 51% from 1981 to 1992.17

Medications given epidurally

include opioid analgesics, anesthetics, or more commonly, both. The

combination has an additive effect.18 Analgesics commonly used for

epidurals include fentanyl and sufentanil, which are better tolerated than

morphine and meperidine. The drawbacks for epidural morphine are its long

onset time and modest effectiveness.

Local anesthetics used in

regional anesthesia include low-dose cocaine derivatives: bupivacaine,

lidocaine, and ropivacaine.11 Common side effects include pruritus,

inability to urinate, and hypotension.

Bupivacaine is a commonly used

local anesthetic, and its advantages include prolonged duration of action, low

placental transfer, and efficacy in both early and late stages of labor.19

Bupivacaine was the first anesthetic of choice for several decades; however,

it fell out of favor in the mid-1980s after several maternal deaths due to

cardiotoxicity of bupivacaine 0.75% solution.20

Lidocaine is used less often

than bupivacaine because it offers less pain relief and has a shorter duration

of action.11 On the other hand, it has a decreased risk of

cardiotoxicity compared to bupivacaine.

Ropivacaine is similar to

bupivacaine in onset, duration, and sensory block; however, ropivacaine is the

S-enantiomer, and bupivacaine is a racemic mixture of both the R and S forms.21

Ropivacaine, like lidocaine, has less risk of cardiotoxicity than does

bupivacaine. Ropivacaine use also reduces the need for instrumental vaginal

deliveries. A meta-analysis by Writer et al. noted a 13% reduction in

instrumental vaginal deliveries with ropivacaine use compared to bupivacaine.22

Efficacy of ultra-low-dose

epidurals and combined spinal epidurals, which are referred to as walking

epidurals, was evaluated in several studies. Low concentrations of

bupivacaine or ropivacaine in combination with fentanyl allowed for sufficient

analgesia along with the majority of patients retaining the ability to

ambulate. A study by Breen et al. noted that low-dose bupivacaine at 0.04%

with fentanyl and epinephrine produced sufficient analgesia with little motor

impairment.23 Campbell et al. reported that 100% of patients

receiving epidural ropivacaine 0.08% with fentanyl 2 mcg/mL were able to

continue ambulating, compared to 75% of the patients receiving bupivacaine

0.08% with fentanyl 2 mcg/mL.24

There are several precautions

to consider for the laboring woman who wishes to ambulate. The patient's blood

pressure as well as fetal heart rate should be monitored for 30 to 60 minutes

after initiation of the epidural and then at least every 30 minutes

thereafter. The patient should demonstrate her ability to walk by either

stepping up and down on a stool or performing knee bends. Finally, the patient

should never ambulate alone.2

Maternal and Labor Effects

of Regional Analgesia

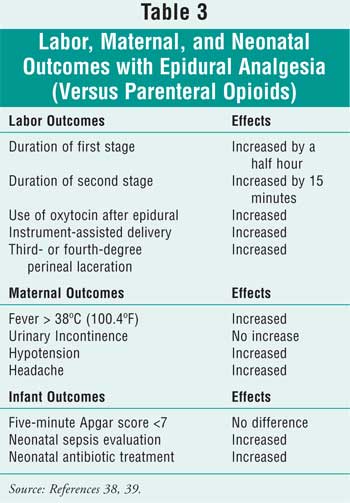

Studies have noted that epidural use is associated with negative effects (see Table 3): increased length of the first and second stages of labor, increased use of forceps or vacuum in deliveries, and maternal fever.

There have also been concerns that

epidural use increases the need for cesarean delivery. Two separate

meta-analyses noted no change in cesarean rates between epidural and

parenteral opioid groups; however, first and second stages of labor were

prolonged in patients in the epidural groups compared to those in the

parenteral opioid groups.25,26 Several studies by Chestnut et al.

have shown that higher concentrations of bupivacaine (0.125% vs. 0.0625% +

0.0002% fentanyl) given epidurally can cause significant motor blockade and

increase the risk of forceps delivery.27-29

Epidural analgesia in labor is

frequently linked to maternal fever with a body temperature higher than 100.4ºF.

One randomized trial observed that 15% of women who received an epidural had a

fever, as compared to only 4% of those who did not receive an epidural. This

percentage increased for those nulliparous women in the study (24% vs. 5%).30

Neonates born to mothers who have received epidurals are more often assessed

and treated with antibiotics due to concerns of possible infection.31

Another concern with epidurals

is puncture of the subarachnoid space during positioning of the epidural

needle. This early complication causes a minuscule quantity of spinal fluid to

seep out into the epidural space, leading to a postdural headache.11

Punctures occur in about 3% of women and account for 70% of severe headaches

in postpartum women.32

General Anesthesia

General

endotracheal anesthesia for emergency cesarean delivery is indicated when

there is severe fetal distress with insufficient time to establish regional

anesthesia, as well as cases of coagulopathy, severe maternal hemorrhage, or

failure of regional anesthesia.1

General anesthesia involves

injection of a rapid-acting induction agent such as thiopental, ketamine, or

etomidate and a short-acting muscle relaxant such as succinylcholine or

rocuronium to cause deep sedation and analgesia, as well as muscle paralysis

and apnea. A tracheal tube is placed, and anesthesia is maintained with

oxygen, an inhalational agent, and nitrous oxide.33

Failure of tracheal intubation

in obstetric patients is nearly 10 times that in nonobstetric patients.34

Capillary swelling of the mucosa in the trachea due to pregnancy reduces the

internal space of the trachea. Anesthesia-related maternal death is the sixth

leading cause of pregnancy-associated deaths in the U.S.35 The

fatality rate for general anesthesia in cesarean delivery is projected at 32

per one million live births versus 1.9 per one million live births for

regional anesthesia.36

Summary

The American

College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists offered this statement in a recent

bulletin: "Labor results in severe pain for many women. There is no other

circumstance in which it is considered acceptable for a person to experience

untreated severe pain, amenable to safe intervention, while under a

physician's care. In the absence of a medical contraindication, maternal

request is a sufficient medical indication for pain relief during labor. Pain

management should be provided whenever it is medically indicated."12

For women suffering from labor

pain, there are many choices available for pain relief. The route of pain

relief will depend on specific circumstances for each patient and the level of

pain experienced.

References

1. Poole JH. Analgesia and anesthesia during labor and birth: implications for mother and fetus. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2003;32:780-793.

2. Gaiser RR. Labor epidurals and outcome. Best Pract Res Clin Anesthesiology. 2005;19:1-16.

3. Belin Y. Advances in labor analgesia. Mount Sinai J Medicine. 2002;Jan/March:38-43.

4. Harmer M, Rosen M. Parenteral opioids. In: Van Zundent A, Ostenheimer GW, eds. Pain Relief and Anaesthesia in Obstetrics. Churchill Livingstone; 1996:365-372.

5. Caton D. Obstetric anesthesia: the first ten years. Anesthesiology. 1970;33:102-109.

6. Von Steinbuchel. Vorlaufige mittheilung uber die anwendung von skopolamin-morphium-injectionem in der Gerburtshilfe. Zentrabl F Gynok. 1902;26:1304.

7. Bricker L, Lavender T. Parenteral opioids for labor pain relief: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:S94-S109.

8. Gogarten W, Van Aken H. A century of regional analgesia in obstetrics. Anesth Analg. 2000;91:773-775.

9. Simkin P, Bolding A. Update on nonpharmacologic approaches to relieve labor pain and prevent suffering. J Midwifery Women's Health. 2004;49:489-504.

10. Soontrapa S, Somboonpron W, Komwilaisak R, et al. Effectiveness of intravenous meperidine for pain relief in the first stage of labour. J Med Assoc Thai. 2002;85:1169-1175.

11. Althaus J, Wax J. Analgesia and anesthesia in labor. Obstet Gynecol Clin N Am. 2005;32:231-244.

12. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 36. Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Obstetric Analgesia Anesthesia. 2002;100:177-191.

13. Manninen T, Aantaa R, Salonen M, et al. A comparison of the hemodynamic effects of paracervical block and epidural anesthesia for labor analgesia. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2000;44:441-445.

14. Rosen MA. Paracervical block for labor analagesia: a brief historic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(5 Suppl):S127-S130.

15. Eltzschig HK, Lieberman ES, Camann WR. Regional anesthesia and analgesia for labor and delivery. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:319-332.

16. Yancey MK, Pierce B, Schweitzer D, et al. Observations on labor epidural analgesia and operative delivery rates. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180(2 Pt 1):353-359.

17. Hawkins JL, Gibbs CP, Orleans M, et al. Obstetric anesthesia work force survey, 1981 versus 1992. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:135-143.

18. Lim Y, Sia AT, Ocampo CE. Comparison of intrathecal levobupivacaine with and without fentanyl in combined spinal epidural for labor analgesia. Med Sci Monit. 2004;10:187-191.

19. Belfrage P, Berlin A, Raabe N, et al. Lumbar epidural analgesia with bupivacaine in labor: drug concentration in maternal and neonatal blood at birth and during the first day of life. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1975;123:839-844.

20. Kuczkowski K. Levobupivacaine and ropivacaine: the new choices for labor analgesia. Int J Clin Pract. 2004;58:604-605.

21. Drysdale SM, Muir H. New techniques and drugs for epidural labor analgesia. Sem Perinatology. 2002;26:99-108.

22. Writer WD, Stienstra R, Eddleston JM, et al. Neonatal outcome and mode of delivery after epidural analgesia for labour with ropivacaine and bupivacaine: a prospective meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 1998;81:713-717.

23. Breen TW, Shapiro T, Glass B, et al. Epidural anesthesia for labor in an ambulatory patient. Anesth Analg. 1993;77:919-924.

24. Campbell DC, Zwack RM, Crone LA, et al. Ambulatory labor epidural analgesia: bupivacaine versus ropivacaine. Anesth Analg. 2000;90:1384-1389.

25. Halpern SH, Leighton BL, Ohlsson A, et al. Effect of epidural vs. parenteral opioid analgesia on the progress of labor. A meta-analysis. JAMA. 1998;280:2105-2110.

26. Sharma SK, McIntire DD, Wiley J, Leveno KJ. Labor analgesia and cesarean delivery: an individual patient meta-analysis of nulliparous women. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:142-148.

27. Chestnut DH, Vandewalker GE,

Owen CL, et al. The influence of continuous epidural bupivacaine analgesia on

the second stage of

labor and method of

delivery in nulliparous women. Anesthesiology. 1987;66:774-780.

28. Chestnut DH, Laszewski LJ, Pollack KL, et al. Continuous epidural infusion of 0.0625% bupivacaine – 0.0002% fentanyl during the second stage of labor. Anesthesiology. 1990;72:613-618.

29. Chestnut DH, Owen CL, Bates JN, et al. Continuous infusion epidural analgesia during labor: a randomized double-blind comparison of 0.0625% bupivacaine/0.0002% fentanyl versus 0.125% bupivacaine. Anesthesiology. 1988;68:754-759.

30. Philip J, Alexander JM, Sharma SK, et al. Epidural analgesia during labor and maternal fever. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:1271-1275.

31. Lieberman E, Lang JM, Frigoletto F Jr, et al. Epidural analgesia, intrapartum fever, and neonatal sepsis evaluation. Pediatrics. 1997;99:415-419.

32. Norris MC, Leighton BL, DeSimone CA. Needle bevel direction and headache after inadvertent dural puncture. Anesthesiology. 1989;70:729-731.

33. Mattingly JE, D'Alessio J, Ramanathan J. Effects of obstetric analgesics and anesthetics on the neonate. Pediatr Drugs. 2003;5:615-627.

34. Samsoon GL, Young JR. Difficult tracheal intubation: a retrospective study. Anaesthesia. 1987;42:487-490.

35. Berg CJ, Atrash HK, Koonin LM, Tucker M. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 1987-1990. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88:161-167.

36. Hawkins JL, Koonin LM, Palmer SK, Gibbs CP. Anesthesia-related deaths during obstetric delivery in the United States, 1979-1990. Anesthesiology. 1997;86:277-284.

37. Campbell DC. Parenteral opioids for labor analgesia. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2003;46:616-622.

38. Lieberman E, O'Donoghue C. Unintended effects of epidural analgesia during labor: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(Suppl 5):S31-S68.

39. Leighton BL, Halpern SH. The

effects of epidural analgesia on labor, maternal, and neonatal outcomes: a

systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(Suppl 5):S69-S77.

To

comment on this article, contact editor@uspharmacist.com.