US Pharm.

2006;31(9):50-71.

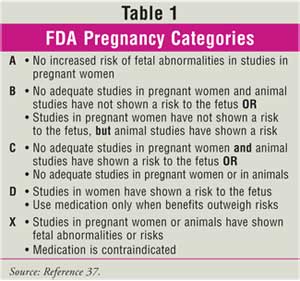

Pregnant

women represent a challenging population to treat with both OTC and

prescription medications. Well-designed, prospective studies are seldom

conducted in pregnant women, and the safety and efficacy of drug therapy is

often unclear (Table 1). Therefore, health care practitioners have only

modest guidance on what medications are safe for use in pregnant women.

Pharmacists face this dilemma on a daily basis with regard to OTC medications

during pregnancy. Herein, the appropriate treatment of six gastrointestinal

(GI)disorders that occur during pregnancy will be reviewed.

Nausea and Vomiting

Nausea and vomiting

of pregnancy (NVP) most commonly affects women in their first trimester. The

frequency of NVP may be variable as up to 85% and 50% of pregnant women

experience nausea and vomiting, respectively.1 Although often

referred to as morning sickness, NVP can occur at any time during the day. The

etiology of NVP is unknown and controversial. Psychological factors, GI tract

dysfunction, and hormonal changes have been studied as possible causes, but

the data are inconclusive. Another study has shown that chronic Helicobacter

pylori infection was significantly more prevalent in pregnant women suffering

from NVP, compared to pregnant women not suffering from NVP.2

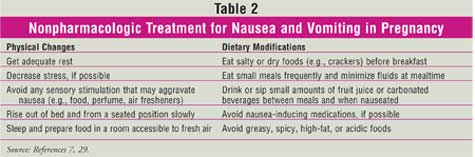

Nonpharmacologic Treatment

Pharmacists should

not recommend pharmacologic treatment for NVP. For mild cases of NVP,

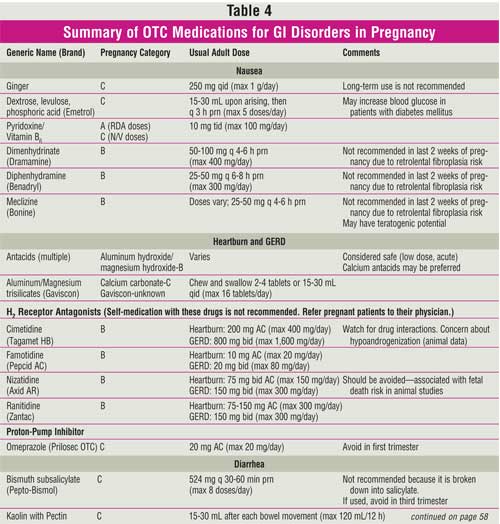

nonpharmacologic methods to prevent nausea (Table 2) can be

recommended. However, pregnant women should always be referred to their

physician if such measures are ineffective or if NVP symptoms are more severe.

Several serious conditions can initially present with moderate to severe

nausea and vomiting. These conditions range from preeclampsia to liver

disorders. If a pregnant patient presents with moderate to severe nausea and

vomiting, she should be referred to her physician for further evaluation.

It is important to assess the

appropriateness of physician recommendations. For nonpharmacologic therapy,

physicians may recommend acupressure. There are conflicting data on the

effectiveness of acupressure bands. However, these devices appear to be safe.

Pharmacologic Treatment

The American

College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) issued recommendations for the

treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy in 2004.3 One

recommendation is for a woman to take a multivitamin while she is trying to

conceive. It has been noted in clinical trials that there may be a lower

incidence of vomiting if women take a multivitamin at the time of conception.

3 Physicians may suggest many drug therapy options to treat NVP,

including pyridoxine, antiemetics, antihistamines, corticosteroids,

antimotility agents, and anticholinergics. In general, drug therapy is

typically reserved for severe cases of NVP after balancing risk versus benefit.

Ginger, on the other hand, has

been shown to decrease nausea and vomiting in cases of hyperemesis gravidarum,

and there are no reports of fetal abnormalities.4,5 Ginger contains

gingerols and shogaols that may directly affect the digestive tract to prevent

nausea and vomiting. Yet, the use of ginger remains controversial. Some warn

against the use of ginger because of possible antiplatelet effects. Ginger

contains thromboxane synthetase inhibitor. This inhibitor may interfere with

testosterone receptor binding in the fetus.6 However, ginger is

used as a spice in other cultures in amounts similar to those used to treat

NVP, and there are no reports of harm caused with these doses.7

Ginger is available in many forms (e.g., ginger ale, ginger root, and

tablets). Administration of 1 g/day in divided doses before meals and at

bedtime has been used to prevent nausea.

Emetrol:

Emetrol, a combination of dextrose, levulose, and phosphoric acid, is used

off-label for treating NVP. This combination of ingredients may act directly

on the GI tract to decrease smooth muscle contraction, thus delaying gastric

emptying. The pregnancy category for Emetrol is unknown. Table 1 lists

pregnancy categories for all medications discussed in this article.

Pyridoxine:

Pyridoxine (vitamin B6), either alone or combined with doxylamine,

has been used to prevent nausea and vomiting. ACOG recommends pyridoxine as

the first step in a pharmacologic treatment plan, due to available safety and

efficacy data. Pyridoxine is pregnancy category A if used at doses comparable

to the recommended daily allowance (RDA) of 2.2 mg. In fact, many pregnant

women may be vitamin B6 deficient, since the demand for this

vitamin increases during pregnancy. Exceeding the RDA is not recommended,

because the pregnancy category falls to a C level at such doses. The

recommended dose of pyridoxine as a treatment for nausea and vomiting ranges

from 10 to 25 mg three to four times daily. The prenatal vitamin PremesisRx

contains 75 mg of pyridoxine. While this combination makes theoretical sense,

this product has not been proved to reduce NVP.3

Pyridoxine was once combined

with doxylamine in a product known as Bendectin, which was withdrawn from the

market in 1983 due to possible birth defects. However, evidence indicates that

this combination may not be teratogenic. Furthermore, doxylamine is pregnancy

category B. In 1983, the FDA regarded three studies as the most conclusive

regarding the teratogenicity of Bendectin but concluded that there was no

definite causal relationship, since nausea and vomiting could increase the

risk of teratogenicity. It was not possible to determine if use of Bendectin

was completely devoid of fetal risk. Bendectin was thus withdrawn from the

market to avoid possible litigation. Pyridoxine-doxylamine (Diclectin) is

available in Canada and is still recommended by U.S. physicians. The standard

dose of doxylamine is 12.5 mg three to four times daily. Doxylamine is

recommended for use in combination with pyridoxine for patients in whom

pyridoxine monotherapy was not effective.3

Anticholinergic

Medications: Women

may also be advised to take antihistamines or anticholinergics such as

meclizine, dimenhydrinate, and diphenhydramine. These medications are used to

treat NVP, due to their effectiveness. All three are rated pregnancy category

B and have not been associated with an increased risk of malformations.3

Common doses are diphenhydramine 25 to 50 mg every four to six hours as

needed or dimenhydrinate 50 to 100 mg every four to six hours as needed.

In summary, no OTC medications

are FDA approved for the treatment of NVP. For women considering becoming

pregnant, a multivitamin should be recommended. If a pregnant patient is

experiencing nausea and/or vomiting, nonpharmacologic treatment can be

suggested as initial therapy. However, if this fails to control symptoms, or

if a woman has moderate to severe nausea and vomiting, she should be referred

to her physician for further evaluation. If an OTC medication is recommended,

it should be used in conjunction with nonpharmacologic measures. Pharmacists

should counsel patients to take the medication on an "as-needed" basis,

rehydrate if necessary, and follow up with their physicians if nausea and/or

vomiting worsens.

GERD/Heartburn

Heartburn or

gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is common during pregnancy and is

reported by about 30% to 50% of pregnant women; the incidence may be as high

as 80% in certain populations.8-10 Although the exact mechanism is

unclear, reduced lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure has a role in the

pathogenesis of GERD in pregnancy. During early pregnancy, the LES pressure

responses to hormonal, pharmacologic, and physiologic stimulation are reduced.

11 The resting LES pressure falls about 33% to 50% of baseline, probably

due to increased progesterone levels.8 Abnormal gastric emptying or

delayed small bowel transit may also contribute to the pathogenesis, but the

impact of increased abdominal pressure due to an enlarging uterus is

controversial.8

Symptoms

GERD symptoms

during pregnancy are similar to those in the general population.8,12

Heartburn is the predominant symptom, but regurgitation also occurs

frequently.8 Symptoms can occur at any time during pregnancy but

are generally worse during the last trimester.9,13 Dietary triggers

that worsen symptoms include fatty foods, spicy foods, and caffeine. Since

GERD during pregnancy usually has a short duration and resolves after

delivery, complications (e.g., esophagitis and stricture) are rare.8

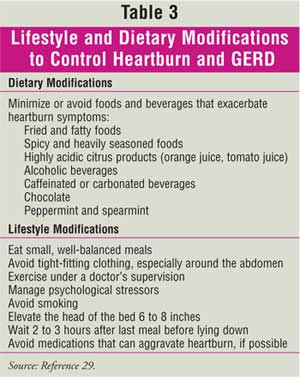

Nonpharmacologic Treatment

The preferred and

safest initial treatment for GERD during pregnancy is lifestyle modification.

Such measures include avoiding foods that trigger symptoms (e.g., spicy or

fatty food) and elevating the head of the bed (see Table 3). Chewing

gum may also help because it stimulates salivary glands, which can help

neutralize acid.8 Lifestyle modifications may control mild symptoms

in women, but drug therapy may be necessary if symptoms are not relieved by

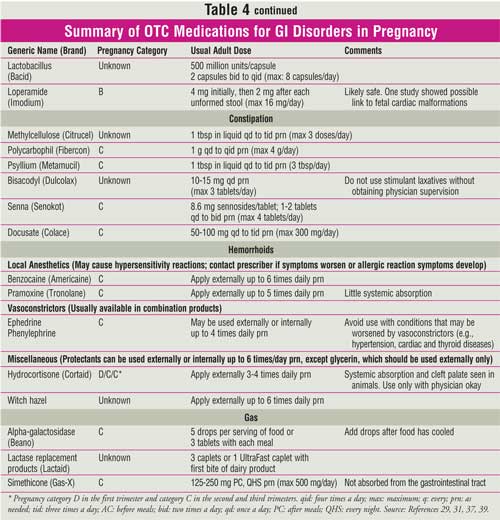

these measures (Table 4).

Antacids

The FDA has not

determined the pregnancy category for antacids, and there are few data on the

effects of antacids on the fetus. In animal studies, magnesium-, aluminum-, or

calcium-based antacids were not teratotogenic.14 One retrospective

case-controlled study reported a significant increase in congenital

malformations in infants with third trimester antacid exposure. However,

analysis of individual antacids found no link to congenital anomalies.15

Antacid use has not been shown to be unsafe, but there have been no

controlled studies.16

Despite the limited data, experts

have agreed that antacids should be the first OTC treatment for heartburn

during pregnancy.12 Antacids provide fast and effective relief, and

up to half of women will require only antacids to control GERD.8

Magnesium-, calcium-, and aluminum-containing antacids at recommended doses

are considered safe to use during pregnancy, although some experts

preferentially recommend calcium/magnesium-containing antacids, because high

doses of aluminum-containing antacids may increase aluminum levels in women

and cause fetal harm.8,12,17

Alginates are generally as

effective as antacids in controlling GERD symptoms.18 A formulation

of Gaviscon that has a lower sodium content was studied in an open-label study

in 150 pregnant women.19 Although effective in relieving heartburn,

adverse events were reported in 10 fetuses.19 Furthermore,

magnesium trisilicate (found in some Gaviscon preparations) may cause fetal

nephrolithiasis, hypotonia, respiratory distress, and cardiovascular

impairment if used long-term and at high doses.19

In summary, calcium- or

magnesium-containing antacids are preferred during pregnancy. Usual dosage of

antacids on an as-needed basis should be recommended. Calcium-based antacids

provide an additional source of calcium during pregnancy, which may help

prevent hypertension and preeclampsia.12 Patients should be

counseled on potential interactions of antacids with other drugs and

supplements such as iron.

Histamine-2 Receptor Antagonists

(H2RAs)

All H2

RAs are FDA pregnancy category B. Cimetidine and ranitidine have been used

safely during pregnancy over the last 30 years.8 Only ranitidine,

however, has been specifically evaluated in heartburn during pregnancy.

Both studies, albeit small and short in duration, showed improvement in

heartburn symptoms with ranitidine and no adverse pregnancy outcomes.9,19

There are no prospective randomized studies on the safety of cimetidine and

other H2RAs during pregnancy, but the general consensus is that

cimetidine and possibly famotidine are safe.8,12 Cohort studies

have shown similar pregnancy outcomes and rates of malformation in women

exposed to H2RAs during the first trimester, compared to controls.

20,21 Although one animal study suggested antiandrogenic effects of

cimetidine and feminization of male offspring, data are conflicting and have

not been reported in humans.8,16,22 Famotidine was not fetally

toxic or teratogenic in animal studies. Animal studies of nizatidine have

conflicting results. One showed no adverse effects on fetal rat pups, but

another study in rabbits given 300 times the recommended dose for humans

resulted in abortions, low fetal weights, and fewer live fetuses. Thus, other H

2RAs may be safer than nizatidine.

For women with refractory

symptoms despite lifestyle modification and antacid use, H2RAs are

commonly used for pregnant women.12 Ranitidine is preferred due to

available data, but cimetidine is likely safe. If symptoms persist with

antacids, physician referral is advised. A pregnant woman should use the

lowest dose necessary (e.g., 75 mg of ranitidine once daily) until she is

evaluated by a physician.

Proton-Pump Inhibitors

(PPIs)

Omeprazole, the

only PPI available OTC, is pregnancy category C. Recent retrospective and

prospective cohort studies suggest that usual doses of omeprazole and other

PPIs during the first trimester do not present a major teratogenic risk in

humans.23-26 A prospective cohort study was conducted on the safety

of PPI use in pregnancy.27 In 410 pregnant women taking PPIs (295,

omeprazole; 62, lansoprazole; 53, pantoprazole) mostly in the first trimester,

the rate of major anomalies was comparable between PPI-exposed women and

controls. Although these data suggest safety of use, PPIs should be used

during pregnancy with medical supervision and only in women with complicated

GERD refractory to other therapies.8,12 These women should be

referred to a medical practitioner for further evaluation and management.

In summary, a pregnant woman

complaining of GERD or heartburn can be instructed to use nonpharmacologic

treatment. Antacid therapy may be recommended if lifestyle modification does

not control symptoms. If symptoms continue, low-dose H2RA therapy

can be used until she can be seen and evaluated by a physician. Omeprazole OTC

should be reserved for patients who are acting on the recommendation of their

physician.

Diarrhea

Diarrhea is

characterized by an increased frequency and decreased consistency of fecal

discharge, compared to a normal bowel movement pattern.28 More than

three bowel movements per day is considered abnormal.29 Diarrhea is

further classified as acute or chronic, based on its onset and duration. Four

mechanisms lead to diarrhea: a change in active ion transport by decreased

sodium absorption or increased chloride secretion, change in intestinal

motility, an increase in luminal osmolarity, and an increase in tissue

hydrostatic pressure.28 Diarrhea in pregnancy is typically linked

to viral or bacterial infection.30 About 80% of diarrhea episodes

are due to viral infection.31 The exact epidemiology of diarrhea in

pregnancy is unknown.28 Complications of diarrhea include

electrolyte imbalance and dehydration.7

Symptoms

Diarrhea symptoms

in pregnancy are similar to those seen in the general population. Patients

with acute diarrhea present with increased bowel movements. Acute diarrhea may

also present with abrupt onset of nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, headache,

fever, chills, and malaise. Stools have a decreased consistency but are never

bloody. It generally lasts 12 to 60 hours. When assessing patients with

diarrhea, it is important to inquire about the frequency, volume, consistency,

and color of stools.28

Nonpharmacologic Treatment

The first step in

treating diarrhea is rehydration of fluids and electrolytes. Oral replacement

therapy (ORT) can be used to treat nearly all cases of diarrhea. The World

Health Organization recommends oral rehydration solutions that take advantage

of the sodium/glucose couples active absorption mechanism. These solutions

contain sodium and glucose and are formulated with a concentration and

osmolality similar to luminal fluid.30 ORT options include

decaffeinated beverages and juices. Sorbitol-containing ORTs should be

avoided, as they may worsen preexisting diarrhea. Patients should also be

advised to minimize or avoid caffeine, alcohol, and sugary beverage intake,

because these products may also worsen preexisting diarrhea. If the patient

has worsening diarrhea or is unable to keep up her diarrhea losses, she should

be referred to her physician. If the patient has stupor, coma, intestinal

ileus, or protracted vomiting, she should be taken to the emergency department

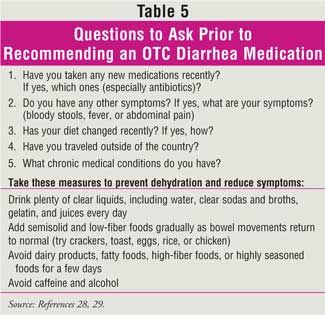

for further evaluation.30 Additional questions to ask to determine

whether OTC diarrhea treatment or physician referral is necessary are shown in

Table 5.

Opiates and Opiate

Derivatives

Opiate and opioid

derivatives work by delaying the transit of intraluminal content or by

increasing gut capacity, prolonging contact and absorption. Most opiates work

peripherally and centrally. Loperamide, the only opiate derivative available

OTC, is the exception and works peripherally. It has antisecretory effects and

works by inhibiting the calcium-binding protein calmodulin and by controlling

chloride secretion.28 Loperamide is pregnancy category B, and its

use in pregnancy has not been associated with major malformations.30,32

However, one study showed that there may be a link between loper amide

use and fetal cardiac malformation.31

Adsorbents

Adsorbents such as

attapulgite, kaolin, polycarbophil, and pectin are used for symptomatic relief

in mild diarrhea. There is little evidence of their efficacy, and they may not

alter stool frequency, stool fluid losses, or the duration of diarrhea.

Adsorbents have a nonspecific mechanism of action. These compounds may adsorb

nutrients, toxins, drugs, bacteria, and digestive enzymes in the GI tract.

28 According to the FDA, polycarbophil is the only effective adsorbent

agent. Polycarbophil may modify watery stool output by absorbing up to 60

times its weight in water.29 Adverse effects of adsorbents are

constipation, bloating, and fullness.28 These products are

pregnancy category B.30

Bismuth Subsalicylate

Bismuth

subsalicylate has antisecretory, anti-inflammatory, and antibacterial effects.

28 It works by reacting with hydrochloric acid in the stomach to form

bismuth oxychloride and salicylic acid.29 It reduces the frequency

of unformed stools, increases stool consistency, and relieves symptoms of

abdominal cramping, nausea, and vomiting.28 Bismuth subsalicylate

is pregnancy category C.30 Similar to other salicylate products,

bismuth subsalicylate should not be used in the second and third trimesters

due to risks to the mother and fetus. These risks include premature closure of

the ductus arteriosus, bleeding, and potential for increased perinatal

mortality.33 This product should be used only under the supervision

of the patient's physician.31

Digestive Enzymes

Lactobacillus

acidophilus is a

digestive enzyme that helps shorten the course of diarrhea by restoring the

normal flora. It may prevent changes in fecal flora and the resulting diarrhea

associated with antibiotics.28 Limited data suggest no link between

lactobacillus use and congenital abnormalities, but further research is needed.

34

A

variety of OTC products are available to treat diarrhea. Many are pregnancy

category B; however, pregnant women should consult their physician prior to

using any OTC medications for diarrhea. For pregnant patients with mild

diarrhea and minimal dehydration, it is safe to recommend ORT.

Constipation

Constipation

affects 11% to 38% of pregnancies.35 As in GERD, increasing

progesterone levels have been implicated in the pathogenesis of constipation.

Progesterone can decrease GI motility and may inhibit motilin, which also

affects GI transit time.33 The effects of progesterone combined

with decreased GI motility can cause constipation during pregnancy. Other

predisposing factors for constipation include iron supplementation and an

enlarging gravid uterus.33 The symptoms of constipation that a

pregnant patient experiences are comparable to those of nonpregnant adults.

These include straining, feelings of incomplete evacuation, and changes in

stool frequency and/or consistency.12 If a pregnant woman develops

abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, weight loss, rectal bleeding, or cramping

with constipation, she should be referred to a physician immediately.29

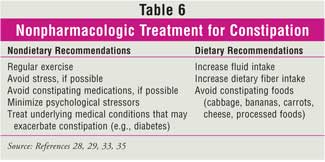

Nonpharmacologic Treatment

Lifestyle

modification is the preferred and safest initial treatment for constipation

during pregnancy. Modifications include increasing dietary fiber, liquid

intake, and physical activity. Fiber therapy has been shown to increase stool

frequency and soften formed stools.35 Yet, there are conflicting

data on fiber's efficacy in treating constipation. The type of fiber may be

one reason for this discrepancy. Some types of fiber, such as bran, are poorly

absorbed. This type is better able to absorb water and is therefore more

effective. Sources of fiber include pharmacologic or dietary supplementation.

Supplementation should be gradual to lessen bloating and gas. Surprisingly,

increasing fluid intake is also controversial. Increased fluids work best for

constipated patients who are dehydrated.36 Liquid intake may be

compromised by nausea and vomiting, especially in the first trimester.

Minimizing the intake of foods that may lead to constipation, such as bananas,

cabbage, or beans, may also be beneficial. While controversial, lifestyle and

dietary modifications may be sufficient to control mild constipation.

Physician referral and drug therapy may be necessary if symptoms are not

relieved by these measures (Table 6).

Bulk-Forming Laxatives

Bulk-forming

laxatives are advised for use in pregnancy, but most are pregnancy category C.

This recommendation is based on their limited systemic absorption and good

safety profile. Three common bulk-forming laxatives are available for general

use: methylcellulose, polycarbophil, and psyllium. These agents work by

increasing the water contained in stool, which improves stool weight and

consistency.33 The bulkier stool, in turn, stimulates peristalsis.

Paradoxically, the increase in stool consistency is also the reason why these

agents can be used for the treatment of diarrhea. Bulk-forming agents can

cause flatulence and/or bloating, which may already be a problem for this

patient population. These adverse effects can be minimized by increasing fluid

intake and by careful dose titration. Increased fluid intake will also

decrease esophageal irritation/obstruction. Psyllium has been associated with

allergic reactions, including anaphylaxis.12 Common doses are

listed in Table 4.

Docusate

Docusate works

differently than other laxatives. Docusate decreases stool surface tension,

which increases the fluid content of the stool, thereby softening stools.

33 Docusate is pregnancy category C but undergoes minimal systemic

absorption and has not been associated with congenital defects.34,37

To relieve possible constipation with prenatal vitamins, some vitamins also

contain docusate. This is an appropriate option after a patient has not

achieved relief using nonpharmacologic measures and bulk-forming laxatives.

Stimulant Laxatives

Stimulant laxatives

may be reserved for patients whose symptoms do not improve with

nonpharmacologic treatment and bulk-forming laxatives or docusate. Their use

should be infrequent, not habitual. The most common stimulant laxatives are

bisacodyl and senna, which are pregnancy category C. These products act on the

colon to stimulate motility. It is this mechanism of action that predisposes

them to a higher incidence of diarrhea and abdominal pain than with

bulk-forming laxatives.35 Common doses are 5 to 15 mg of bisacodyl

orally per day or 10 mg suppository rectally per day and 1 to 2 tablets of

senna orally twice daily. Senna has not been shown to be teratogenic in

animals or humans.33,34,37

Numerous laxatives are available OTC, but

they should be used sparingly. Mineral oil should be avoided, since it can

decrease vitamin absorption and may increase the risk of lipid pneumonia.

29,33,38,39 Castor oil may cause uterine contractions and should not be

used in pregnancy.33,38 Magnesium and saline laxatives are not

recommended in pregnancy because of their potential effects on the patient's

electrolyte balance and ability of the latter to cause water retention.

29,33,38 The potential for adverse events due to osmotic laxatives is

higher in patients with preexisting renal disease or heart failure.

In summary, constipation during pregnancy

should first be treated with nonpharmacologic therapy. Then, products that are

not systemically absorbed should be used, such as bulk-forming laxatives.

29,30 Stimulant laxatives are second-line therapy and are recommended

only if increased dietary fiber and bulk-forming laxatives fail to relieve

constipation. Consultation with a physician is recommended prior to using

pharmacologic agents.

Hemorrhoids

Hemorrhoids have been frequently

reported in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy. Although the

etiology of hemorrhoids is unclear, several factors involved in the

pathogenesis are well known. These factors include preexisting bowel disease,

a low-fiber diet, straining with defecation, and vascular engorgement due to

increased pressure caused by the enlarging abdomen.33

Symptoms

Hemorrhoids can

present with symptoms similar to other anorectal disorders. The pharmacist

should verify that the patient has had her symptoms evaluated by a physician

before recommending a therapy. Swelling, itching, and burning are common

symptoms and are similar to symptoms seen in nonpregnant adults.40

Before making any recommendations, the severity of the patient's symptoms

should be assessed. Pain, severe symptoms, bleeding, fecal seepage, rectal

protrusion, bowel habit changes, and a family history of colon cancer all

merit immediate physician evaluation.29

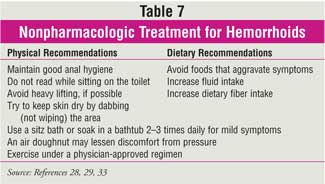

Nonpharmacologic Treatment

As with other GI

complaints, hemorrhoids should be treated nonpharmacologically with increasing

dietary liquid and fiber. Foods and beverages that cause or aggravate symptoms

should be restricted. Soaking in warm water in a sitz bath or a bathtub may

also provide relief. Due to the relationship between straining and

constipation and hemorrhoids, many treatments for constipation are also

appropriate for hemorrhoids. Avoiding constipation and contributing factors to

constipation will help improve symptoms. Nonpharmacologic measures that can

provide relief are summarized in Table 7.

Pharmacologic Treatment

Local anesthetics,

vasoconstrictors, topical corticosteroids, protectants, and astringents may be

used to treat hemorrhoids. Topical anesthetics help relieve itching, burning,

and pain.33 Absorption is minimal unless the skin is chafed. These

products should be applied externally to the skin, and the patient should be

counseled to watch for allergic reactions, which may mimic their hemorrhoid

symptoms. Some vasoconstrictors are ephedrine, epinephrine, and phenylephrine.

These agents decrease swelling but should not be used in pregnant women who

have medical conditions that may be exacerbated by vasoconstriction, such as

hypertension. It is difficult to assess the safety of vasoconstrictors in

pregnancy because they are usually available in combination products. Topical

hydrocortisone is another option for pain and itching relief. Several

protectant products (e.g., petrolatum) are available and prevent further skin

damage by providing a barrier against moisture. Petrolatum has poor absorption

and is considered safe in pregnancy.29 Astringents such as witch

hazel can sting, which may also exacerbate underlying symptoms. These topical

agents have not been adequately evaluated for safety and efficacy in pregnant

patients. Of all of these options, topical anesthetics, astringents, and skin

protectants are likely the most safe. However, due to limited safety data,

these products should be used under a physician's supervision.

Conservative management for hemorrhoids is

aimed at pain relief and stool softening. Other options for external

hemorrhoids are topical anesthetics, vasoconstrictors, protectants,

astringents, and topical corticosteroids. For pain relief, acetaminophen

(pregnancy category B) can be recommended. NSAIDs should be avoided, as they

may worsen bleeding and are pregnancy category D in the third trimester.

Low-strength corticosteroid creams and/or witch hazel can be used for itching.

33 If used, topical corticosteroids should be applied in the smallest

amount and for the shortest duration possible. Docusate can also be used to

soften stools. Due to the lack of safety information regarding these products

in pregnant patients and potential hemorrhoid complications that may be masked

by inappropriate treatment, a physician should be consulted prior to

recommending OTC products for hemorrhoid treatment.29

Conservative options are recommended to

treat hemorrhoids during pregnancy. Since constipation may exacerbate

hemorrhoids, prevention and treatment of constipation is also recommended. A

physician should be consulted to evaluate other options if pain is not

relieved by conservative methods. The patient should contact her physician if

symptoms worsen, persist for more than seven days, or if hemorrhoids are

linked to severe pain, protrusion, bleeding, or fecal seepage.29

GI Gas

GI gas manifests in

two forms: belching and flatulence. Belching, also known as eructation,

is the voluntary or involuntary release of gas from the esophagus or stomach.

Belching mainly occurs after a meal, due to the relaxation of the LES. Most of

the gas in the stomach comes from swallowing air. When too much air is

swallowed, an individual may experience flatulence or abdominal pain, as well

as belching. Chewing gum, eating rapidly, smoking, and drinking carbonated

beverages may contribute to excessive ingestion of air. Flatulence occurs due

to gas trapped in the digestive tract, when air is swallowed, or when bacteria

in the large intestine breaks down undigested food.41 One study

demonstrated that most healthy adults excrete gas an average of 10 times a

day; however, other experts state that individuals may pass gas as much as 14

times each day.42,43

Although gas can affect anyone, it can be

problematic in pregnant women. One cause is progesterone, which is produced

during the early stages of pregnancy. Since progesterone relaxes the smooth

muscles, including the intestinal tract, digestion is slowed, leading to

increased stomach and intestinal gas. Slowed digestion also gives the

intestinal bacteria more time to ferment the undigested food, resulting in

more gas production.44

Pharmacologic Treatment

Gas in pregnant

women can be treated with nonprescription medications. Some products that

contain simethicone, a common treatment for gas, include Gas-X, Phazyme,

Mylanta Gas Softgels, and Mylicon drops. This OTC medication relieves gas in

the stomach and intestine by reducing the surface tension of gas bubbles. By

altering the surface tension, the gas bubbles break and are able to be

eliminated by belching or flatulence. Since simethicone is not absorbed from

the GI tract, there are no known systemic side effects. It is pregnancy

category C, and no congenital defects have been reported.37

Another treatment is

alpha-galactosidase. Products that contain this enzyme include Beano and Gaz

Away. This OTC medication hydrolyzes high-fiber foods and other foods that

contain oligosaccharides before they can be metabolized by the bacteria in the

large intestine. The recommended dose is adding about five drops to each

serving of problematic food or taking three tablets with each meal. Five drops

or three tablets contain 150 units of alpha-galactosidase. Drops should be

added to the food after it has cooled. Other OTC options are lactase

replacement products, such as Dairy Ease, Lactaid, and SureLac tablets.

Lactase replacement may be effective for patients who are intolerant to

lactose. These products break down lactose into glucose and galactose and are

to be taken when dairy products are ingested. As lactase replacement acts

locally in the gut, there are no reported systemic side effects. Pregnant

women should check with their physician before taking these OTC medications.

29,45

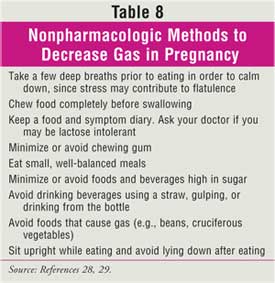

Many pregnant women can

control gas by making dietary changes. Table 8 lists nonpharmacologic

approaches to managing gas in pregnancy.29,46 One main change is to

limit the amount of gas-producing foods in the diet or totally eliminate foods

that are not tolerated.

Conclusion

Pregnant patients

may present with a variety of GI complaints. Nonpharmacologic and lifestyle

modifications can be recommended with or without concomitant pharmacologic

treatment. However, prior to recommending pharmacologic therapy, the patient

should be evaluated by a physician. Pharmacists represent a key part of the

health care team and can assess whether a pregnant patient's symptoms require

immediate physician referral. Additionally, pharmacists can assist

patients and physicians with product selection based on available safety data.

Once a product is selected, the pharmacist can counsel the patient on

appropriate dosage and usage.

References

1. Jewell D, Young G. Interventions for nausea and vomiting in early

pregnancy. Cochrane Database Sys Rev 2003;4:CD000145.

2. Hayakawa S, et al. Frequent presence of Helicobacter pylori genome in the

saliva of patients with hyperemesis gravidarum. Am J Perinatol.

2000;17:243-247.

3. American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG). ACOG Practice

Bulletin Number 52: Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol.

2004;103:803-814.

4. Vutyavanich T, et al. Ginger for nausea and vomiting in pregnancy: a

randomized, double-masked placebo-controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol.

2001;97:577-582.

5. Keating A, Chez RA. Ginger syrup as an antiemetic in early pregnancy.

Altern Ther Health Med. 2002;8:89-91.

6. Backon J. Ginger in preventing nausea and vomiting of pregnancy; a caveat

due to its thromboxane synthetase activity and effect on testosterone binding.

Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1991;42:163-164.

7. Mazzotta P, Magee LA. A risk-benefit assessment of pharmacological and

nonpharmacological treatments for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Drugs

. 2000;59:781-800.

8. Richter JE. Review article: the management of heartburn in pregnancy.

Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:749-757.

9. Larson JD, Patatanian E, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of

ranitidine for gastroesophageal reflux symptoms during pregnancy. Obstet

Gynecol. 1997;90:83-87.

10. Knudsen A, Lebech M, Hansen M. Upper gastrointestinal symptoms in the

third trimester of the normal pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Reprod Biol.

1995;60:29-33.

11. Fisher RS, Roberts GS, et al. Altered lower esophageal sphincter function

during early pregnancy. Gastroenterology. 1978;74:1233-1237.

12. Tytgat GN, Heading RC, et al. Contemporary understanding and management of

reflux and constipation in the general population and pregnancy: a consensus

meeting. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:291-301.

13. Marrero JM, Goggin PM, et al. Determinants of pregnancy heartburn. Br J

Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;99:731-734.

14. Ching C, Lam S. Antacids: indications and limitation. Drugs. 1994;

47: 305-317.

15. Witter FR, King TM, Blake DA. The effects of chronic gastrointestinal

medication on the fetus and neonate. Obstet Gynecol. 1981;58:79S-84S.

16. Smallwood RA, et al. Safety of acid-suppressing drugs. Dig Dis Sci.

1995;40(Suppl):63S-80S.

17. Weberg R, Berstad A, Ladehaug B. Are aluminum containing antacids during

pregnancy safe? Acta Pharmacol Toxicol. 1986;59(Suppl 7):63-65.

18. Mandel KG, Daggy BP, et al. Review article: alginate-raft formulations in

the treatment of heartburn and acid reflux. Aliment Pharmacol Ther.

2000;14:669-690.

19. Lindow SW, Regnell P, et al. An open-label, multicentre study to assess

the safety and efficacy of a novel reflux suppressant (Gaviscon Advance) in

the treatment of heartburn during pregnancy. Int J Clin Pract.

2003;57:175-179.

20. Magee LA, Inocencion G, et al. Safety of first trimester exposure to

histamine H2 blockers. A prospective cohort study. Dig Dis Sci.

1996;41:1145-1149.

21. Ruigomez A, Rodriguez LAG, et al. Use of cimetidine, omeprazole, and

ranitidine in pregnant women and pregnancy outcomes. Am J Epidemiol.

1999;150:476-481.

22. Parker S, Schade RR, et al. Prenatal and neonatal exposure of male rat

pups to cimetidine but not ranitidine adversely affects subsequent adult

sexual functioning. Gastroenterology. 1984;86:675-680.

23. Nielson GL, Sorensen HT, et al. The safety of proton pump inhibitors in

pregnancy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:1085-1089.

24. Lalkin A, Loebstein R, et al. The safety of omeprazole during pregnancy: a

multicenter prospective controlled study. Am J Obstet Gynecol.

1998;179:727-730.

25. Kallen B. Delivery outcome after the use of acid-suppressing drugs in

early pregnancy with special reference to omeprazole. Br J Obstet Gynaecol

. 1998;105:877-881.

26. Nikfar S, Abdollahi M, et al. Use of proton pump inhibitors during

pregnancy and rates of major malformations. A meta-analysis. Dig Dis Sci

. 2002;47:1526-1529.

27. Diavcitrin O, Arnon J, et al. The safety of proton pump inhibitors in

pregnancy: a multicenter prospective controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther.

2005;21:269-275.

28. DiPiro J, et al. Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach. 5th

ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2002:655-669.

29. Berardi R, McDermott J, et al. Handbook of Nonprescription Drugs.

14th ed. Washington, DC: American Pharmacists Association; 2004:335-359.

30. Forrester A. Diarrhea. Patient Self-Care (PSC). 2002:238-251.

31. Black R, Hill DA. Over-the-counter medications in pregnancy. Am Family

Phys. 2003;67:2517-2524.

32. Einarson A, Mastroiacovo P, et al. Prospective controlled multicenter

study of loper amide in pregnancy. Can J Gastroenterol.

2000;14:185-187.

33. Wald A. Constipation, diarrhea, and symptomatic hemorrhoids during

pregnancy. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 2003;32:309-322.

34. Friedman JM, Polifka JE. Teratogenic Effects of Drugs: A Resource for

Clinicians. 2nd ed. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2000.

35. Jewell D, Young G. Interventions for treating constipation in pregnancy.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;2:CD001142.

36. Muller-Lissner SA, Kamm MA, et al. Myths and misconceptions about chronic

constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:232-242.

37. Briggs GG, et al. Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation. 7th ed.

Philadelphia: Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

38. Baron TH, Ramirez B, Richter JE. Gastrointestinal motility disorders

during pregnancy. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:366-375.

39. Thomson Micromedex. USPDI Drug Information for the Health Care

Professional: Volume 1. 25th ed. Taunton, MA: Quebecor World; 2005.

40. Quijano CE, Abalos E. Conservative management of symptomatic and/or

complicated haemorrhoids in pregnancy and the puerperium. Cochrane Database

Sys Rev. 2005;3:CD004077.

41. Tierney LM, et al. Current Medical Diagnosis and Treatment 2006.

Gastroenterology. University of Cincinatti library Web site. Available

at:www.accessmedicine.com/content.aspx?aID=6395. Accessed August 28, 2006.

42. Furne JK, Levitt MD. Factors influencing frequency of flatus emission by

healthy subjects. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:1631-1635.

43. Basotti G, et al. Flatus–related colorectal and anal motor events.

Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:335-338.

44. Gas and bloating during pregnancy. Baby Center. February 2005. Available

at: www.babycenter.com/refcap/pregnancy/prenatal health/247.html. Accessed

February 16, 2006.

45. Clinical Pharmacology (online version). Accessed at University of

Cincinatti library Web site. Available at:www.cpip.gsm.com. Accessed August

28, 2006.

46. Health A to Z. Aetna InteliHealth Inc. February 2004. Available at:

www.intelihealth.com/IH/ihtIH/WSIHW000/8270/22025/346741.html. Accessed

February 16, 2006.

To comment on this article,

contact editor@uspharmacist.com.