US

Pharm. 2006;6:72-77.

Whether preparing for a backyard

barbecue or an Amazon adventure, people need to take some simple steps to

avoid insect bites--practices that could protect them from potentially

life-threatening diseases carried by insects. The insects and other arthropods

that transmit disease to humans include mosquitoes, ticks, flies, chiggers,

fleas, and lice. From West Nile virus to malaria, these tiny vectors transmit

a host of diseases both here in the United States and abroad. Therefore, it is

important to be aware of the behavioral, physical, and chemical defenses

available.

Travel-Related Diseases

In 2004, approximately 763

million people worldwide traveled across international borders; most of them

were simply vacationing.1 Many travel destinations are developing

nations, where insect-borne diseases are more likely to occur. The Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) receives reports of more than 1,000 cases

of malaria every year in people returning to the U.S. from other countries.

2 In fact, the most common cause of fever in someone returning from a

trip to the tropics is dengue fever--a viral disease in the family of yellow

fever--and malaria.3 However, travelling to Africa is not the

only way to encounter a potentially deadly mosquito-borne disease. West Nile

virus is transmitted by the Culex mosquito in all but a couple of

states in the U.S. In 2005, there were nearly 3,000 cases, with 116 deaths.

4 Although most people who use an insect repellent do so for mosquito

protection, they should also be aware of other arthropod-borne diseases such

as Lyme disease (tick bite), murine typhus (flea bite), and African sleeping

sickness (Tsetse fly bite). The CDC's Travelers' Health Web site

(www.cdc.gov/travel) can provide patients and health professionals with a vast

amount of information on diseases associated with travel. With a few

exceptions, if you don't get an insect bite, you can't get the disease it

carries.

Why People Get Bites

Mosquitoes are specially equipped

to find us during the day or night. They use a combination of visual,

chemical, and olfactory senses to locate a blood meal. From a distance,

mosquitoes that bite during the day can detect motion and bright colors.

Carbon dioxide, which we exhale and release from our skin, makes a powerful

attractant from up to 36 meters.5 Although we can't stop breathing,

people should avoid wearing strong perfumes and colognes or using scented

soaps, which may also attract mosquitoes. As the mosquito closes in, it can

still detect carbon dioxide, but it can also sense body heat and lactic acid,

all of which are increased with physical activity. Other factors that may

increase a person's chance of being bitten include being male, overweight, or

an adult.5 The type of mosquito and the availability of a primary

host other than people determine how aggressive a biter of humans they may be.

Many mosquitoes in South America, Africa, and Asia are aggressive biters--they

are less deterred by typical insect avoidance methods than our domestic ones

are. Thus, a higher level of insect precaution compliance is needed with

international travel.

PERSONAL PROTECTIVE MEASURES

Behavior Modification

If possible, people should avoid

typical insect habitats. These habitats may vary by geographic location, time

of the day, season, temperature, and urban versus rural environments. Heavily

forested areas or locations surrounding bodies of standing water, such as a

brackish lake, are more likely to be mosquito breeding grounds. Ticks prefer

low-lying brush in heavily wooded areas where they can sit and wait for a leg

to brush up against their perch. Since ticks do not jump or fly, they need

this close contact to attach to clothes where they can crawl to a bare part of

a leg and attach. Thus, visual inspection for attached ticks and then prompt

removal effectively minimizes the chance of acquiring a tick-borne infection.

The abundance of insects can be affected by

the temperature and season. Typically, mosquitoes are more common during

summer and fall months in temperate climates and following the rainy season in

the tropics. However, it takes only one bite by a mosquito carrying yellow

fever or malaria, for example, to transmit these deadly diseases. Thus, all

relevant insect precautions should be taken even when mosquito populations are

less intense.

Some mosquitoes are active at night and some

during the day. For example, peak biting times of the Aedes mosquito,

which carries yellow fever, dengue fever, and chikungunya viruses, are dawn

and dusk. The Anopheles mosquito carries malaria and bites only at

night between dusk and dawn. Knowing when certain mosquito-borne diseases are

more likely to be transmitted can help determine the appropriate intervention.

In some countries, such as Cambodia, both malaria and dengue fever occur,

necessitating the use of insect precautions day and night.

Insects may have a predisposition for rural

areas or for the city life. Dengue fever is an example of a disease spread by

an urban mosquito that has adapted its breeding grounds to places like old

tires, tin cans, or even puddles. Malaria, however, is mainly found in rural

areas of the tropics and subtropics, but there are notable exceptions, such as

India, where it occurs in rural and urban locations. When traveling to

malarious areas, it is important to know the cities to be visited, as some

have done a good job of mosquito breeding site cleanup, rendering the city

free of malaria. For example, in Nairobi, Kenya, there is no malaria, but

virtually everywhere else in Kenya it exists.

General advice for behavior modifications to

avoid insect bites would include staying indoors in a well-screened

air-conditioned room during peak biting times, avoiding outdoor exposure at

dusk, and not wearing bright clothing or perfumes.

Physical Barriers

Seek to put distance between you

and the blood-sucking insect looking for a meal. To protect against flying

insects, wear long-sleeved shirts and pants, as well as a hat. For ticks, make

sure to wear boots or other shoes that cover your ankles, and tuck your pants

into your shoes or socks. To decrease the chance of a mosquito biting through

your clothes, permethrin can be applied to clothing, or permethrin-treated

clothes can be purchased. Permethrin is a synthetic pyrethroid compound used

for its insecticide and insect repellent properties and is often referred to

as a "knock-down" insecticide. It is odorless, colorless, and won't affect the

material on which it is applied. This is the same chemical in products

available over the counter for killing head lice, so it is relatively safe. To

treat clothing before going out, apply a 0.5% spray to the surface of the

clothing, or soak clothing in a higher concentration. The treated clothes,

either sprayed or soaked, should protect for two weeks or two washings and up

to four weeks or six washings, respectively. When staying in regions where

insects bite at night, people should sleep under bed netting. In addition,

mosquito bed nets can be soaked in permethrin or purchased presoaked.

Insect Repellents

Whenever there is a risk of

contracting arthropod-borne disease, insect repellents should be applied to

exposed intact skin, never under clothing. Other general recommendations for

safe use of insect repellents are to apply it to an adult's hands and then to

the face with the hands, rather than spraying directly; never let young

children apply it to themselves; and wash off repellent when it is no longer

needed. Natural and synthetic repellents are available with variable efficacy

and safety.

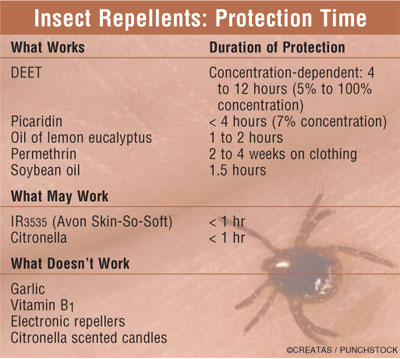

The CDC officially endorses two ingredients

with proven efficacy, DEET and picaridin, for domestic and international use.

For domestic mosquitoes, the CDC also sanctions the use of Environmental

Protection Agency (EPA)–registered repellents containing PMD (p-menthane

3,8-diol), the active ingredient of oil of lemon eucalyptus (for use in ages >=

3 years).6 See Table for a comparison of select repellents.

DEET:

The insecticide commonly known as DEET (now called N,N

-diethyl-3-methylbenzamide, formerly known as N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide

) was developed for the military and was subsequently marketed to the public

in 1957. It is the most frequently used insect repellent in the world, with an

estimated 38% of the U.S. population applying it annually.7

Although the mechanism is not fully understood, it appears to interfere with

an insect's chemoreceptors for lactic acid. This broad-spectrum insect

repellent is relatively safe for adults and children and is the preferred

insect repellent, according to the CDC.8 DEET is an organic solvent

and in higher concentrations can dissolve synthetic material such as plastic

and rayon. The EPA considers it safe to humans and the environment. The

American Academy of Pediatrics considers it safe in concentrations between 10%

and 30%.9 DEET is available over the counter in concentrations

ranging from 5% to 100%. Above 50% concentration, little more protection is

gained, just increased duration of action. The optimal concentration for four

to six hours of protection is 20% to 35%. To increase the duration of action

to eight to 12 hours without having to increase the concentration beyond 20%

to 30%, sustained-release formulations are available.

When insect repellent is applied during the

day, people are often outside in the sun, where sunscreen is also necessary.

DEET repellents should be applied more than an hour after the application of

sunscreen, as DEET can reduce the effect of the sun protection factor (SPF) an

average of 33%.10 Combination DEET and sunscreen products should be

avoided, as they have not been clinically evaluated. It is estimated that for

every 10°C increase in outside temperature, 50% of an insect repellent's

duration of action is lost to evaporation.5 Thus, frequent

reapplication of DEET may be necessary, especially if one is swimming or

sweating excessively.

Picaridin:

Picaridin, also known as Bayrepel or KBR 3023, is a relatively new,

piperidine-based insect repellent in the U.S. It is touted as less irritating,

less smelly, and less damaging to clothing than DEET. Both DEET and picaridin,

however, are reported by the EPA to have a low potential for toxicity to

humans or the environment.11 Picaridin is marketed in the U.S. in a

concentration of 7%, but field testing with this compound was done on a 19.2%

concentration, roughly equivalent to DEET 20%.12 Thus, if you are

recommending picaridin, you should emphasize that it needs to be reapplied

more frequently than every four hours, especially in the tropics, due to the

low concentration available in the U.S.

Miscellaneous:

Although not originally introduced to repel insects, Avon's

Skin-So-Soft product was subsequently found to do so. The main ingredient is

butylacetylaminopropionate, or IR3535, an amino acid analog. IR3535 is

registered with the EPA as a pesticide against mosquitoes, ticks, and biting

flies, but it has a short duration of action. There is little clinical data on

IR3535, but in one large clinical study, it protected for only about 23

minutes.13

Botanicals:

Unlike the previous three synthetic insect repellents, the following are

derived from plant sources. Oil of lemon eucalyptus, also known as PMD, was

recently endorsed by the CDC against carriers of West Nile virus and other

domestic mosquitoes.6 This pleasant-smelling menthol-like repellent

at 30% is approximately equivalent to the protection of DEET 20% but does not

last as long; it must be applied more often than every four hours.

Citronella is a popular ingredient in

everything from sprays to candles and coils that are burned. Although it

smells nice, it offers less than an hour of protection per application; when

used as the candle or coil, it gives the same effect as does burning a regular

candle.7

The only other product clinically tested to

have protection against mosquitoes is a soybean oil–based product marketed as

Blocker. It provides protection similar to a 4.75% DEET or about 1.5 hours.

13

No other products have shown any clinically

proven efficacy, including vitamin B1 (thiamine) and garlic. In 1985, the

FDA responded to the increased anecdotal accounts of vitamin B1's

effectiveness as an insect repellent by issuing a statement refuting any

claims of efficacy and prohibiting manufacturers from doing the same for any

oral product.14

Treating the Bite

The main objective in caring for

mosquito bites is to reduce inflammation and itching that might lead to

superinfection of the bite site. Topical corticosteroids work fairly well at

reducing itching and inflammation. Oral antihistamines, particularly

cetirizine, also work well at reducing the redness and itching.15

An ammonium solution marketed as Afterbite was shown to be effective, at least

temporarily, in nearly everyone who used it.16

Conclusion

Although yellow fever and malaria

have been eradicated in the U.S. in the last century, other potentially deadly

mosquito-borne diseases such as West Nile virus and dengue fever have recently

emerged here. Thus, the need to protect against mosquitoes and other biting

arthropods both in the U.S. and abroad is great. Counseling patients on the

importance of personal protective measures will help to ensure safe and

enjoyable outdoor experiences.

References

1. Hill DR. The burden of illness

in international travelers. N Engl J Med 2006;354:115-117.

2. Shah S, Filler S, Causer LM, et

al. Malaria surveillance--United States, 2002. MMWR Surveill Summ

2004;53:21-34.

3. Freedman DO, Weld LH, Kozarsky PE,

et al. Spectrum of disease and relation to place of exposure among ill

returned travelers. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:119-130.

4. 2005 West Nile Virus Activity in

the United States. February 14, 2006. CDC Division of Vector-borne Infectious

Diseases. Available at: www.cdc.gov/ncidod/

dvbid/westnile/surv&controlCaseCount 06_detailed.htm. Accessed April 10, 2006.

5. Fradin MS. Insect protection. In:

Keystone J, Kozarsky P, Freedman D et al., eds. Travel Medicine. Mosby,

2004;61-69.

6. Updated Information Regarding

Mosquito Repellents. April 22, 2005. Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention. Available at:

www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/westnile/RepellentUpdates.htm. Accessed April 3, 2006.

7. Fradin, MS. Mosquitoes and

mosquito repellents: clinician's guide. Ann Intern Med

1998;128:931-940.

8. Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention. Protection against mosquitoes and other arthropods. In: Arguin PM,

Kozarsky PE, Navin AW, eds. Health Information for International Travel

2005-2006 (Yellow Book). Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services,

Public Health Service; 2005.

9. Flake ZA, Hinojosa JR, Brown M, et

al. Clinical inquiries. Is DEET safe for children? J Fam Pract

2005;54:468-469.

10. Montemarano AD, Gupta RK, Burge

JR, et al. Insect repellents and the efficacy of sunscreens. Lancet

1997;349:1670-1671.

11. Environmental Protection Agency:

New Pesticide Fact Sheet: Picaridin. 2005.

12. Frances SP, Waterson DGE, Beebe

NW et al. Field evaluation of repellent formulations containing DEET and

picaridin against mosquitoes in Northern Territory, Australia. J Med Entomol

2004;41:414-17.

13. Fradin MS, Day JF. Comparative

efficacy of insect repellents against mosquito bites. N Engl J Med

2002;347:13-18.

14. FDA. Drug products containing

active ingredients offered over-the-counter (OTC) for oral use as insect

repellents. Federal Register 1985;50,116 (21 CFR Part 310):25170-25171.

Available at

www.fda.gov/cder/otcmonographs/Insect_Repellent/insect_repellant_final_conclusions_19850617.pdf.

15. Reunala T, Brummer-Korvenkontio

H, Karppinen A, et al. Treatment of mosquito bites with cetirizine. Clin

Exp Allergy 1993;23:72-75.

16. Zhai H, Packman EW, Maibach HI.

Effectiveness of ammonium solution in relieving type I mosquito bite symptoms:

a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Acta Derm Venereol

1998;78:297-298.

To comment on this article,

contact

editor@uspharmacist.com.