US Pharm.

2007;32(12):HS-18-HS-26.

Temporomandibular disorders

(TMDs) are the most common type of facial pain condition, affecting

approximately 10% to 12% of the population, with about 25% of individuals

having at least one TMD episode during their lifetime.1

TMDs, which fall under the

category of musculoskeletal disorders, is a collective term used to describe a

number of related conditions affecting the temporomandibular joint (TMJ)

and/or masticatory muscles, all of which have three common symptoms: orofacial

pain, joint noises, and restricted jaw opening during jaw movements such as

speaking or chewing.2 Patients have reported symptoms ranging from

mild (i.e., not requiring treatment) to moderate or severe (i.e., requiring

treatment). In actuality, only about 5% to 6% of patients need treatment, with

women seeking treatment more often than men. Treatment of TMDs is challenging

and controversial in the medical and dental fields.3

Anatomy

The TMJ is a

synovial joint located at the junction of the mandible (lower jaw) and the

temporal bone of the skull (immediately in front of the ear on each side of

the head). A small cushioning disk of cartilage separates the bones, similar

to that in the knee joint, so that the mandible can slide easily. The TMJ

moves upon chewing, yawning, talking, and swallowing. It is easily located by

placing a finger on the triangular structure in front of the ear. The TMJ can

be felt in function by moving the finger slightly forward and pressing firmly

while opening the jaw to the maximum separation of the teeth and then shutting

it.

Classification of TMDs

Many terms have

been used to describe TMDs, including TMJ syndrome and TMJ disease; however,

the term TMD is the preferred term used by the American Academy of

Orofacial Pain (AAOP) and other professionals. Various classifications and

clinical diagnostic criteria exist to describe TMD.

The AAOP defines two

classifications of TMDs: muscle-related, or myogenic, TMD and joint related,

or arthrogenous, TMD.4 Occasionally, both types may be present

simultaneously, making a diagnosis difficult. Myogenic TMD, the more common

form, only involves functional alterations of the masticatory muscles around

the TMJ without TMJ problems. It usually occurs in persons with high stress

and is caused by nocturnal bruxism (teeth grinding) or day- or nighttime teeth

clenching. Arthrogenous TMD may be caused by disk displacement, recurrent

dislocation, degenerative joint disorders, hypermobility of the joint,

osteoarthritis, ankylosis, or neoplasia. Temporomandibular dysfunction occurs

when there is a displacement of the cartilaginous disk, causing pressure and

stretching of the associated muscles and sensory nerves. The characteristic

"clicking" or "popping" occurs when the mandible moves and the disk snaps into

place. Pain is also associated with spasm of the chewing muscles (i.e.,

masseter, temporalis, and pterygoid).

In the past, there was no

reliable and valid method of diagnosing TMD patients, which led to serious

misclassification of TMD cases. However, in 1992, clinical research experts

(with support from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research)

developed and published "Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular

Disorders," which established specific operational examination procedures and

diagnostic criteria that are used in epidemiologic and clinical research for

defining TMD.5 These criteria describe a diagnosis along two

separate axes: the Axis I score provides a clinical diagnosis, while the Axis

II score provides an assessment of the psychological/behavioral aspects.

Etiology

There are many causes, both specific

and nonspecific, of TMJ pain and dysfunction, which continue to be

controversial. One reason for this controversy is that some factors are risk

factors, while others are causal in nature or purely coincidental to the TMD

problem.6,7 Although the etiologies are poorly understood, most

clinicians and researchers suggest a multifactorial etiology for TMD involving

physical, psychological, and social factors.

Physical Factors:

Sustained or repetitive loading of the masticatory system, which occurs

during parafunctional jaw activities--such as bruxism; teeth clenching; pencil

or pen chewing; gum chewing; lip biting; sucking on lips, fingers, and cheek;

and nail biting--can result in muscle hyperactivity and overloading of the TMJ.

8 Bruxism occurs in approximately 6% to 20% of the population and

between 67% and 87.5% of patients with TMD.9 Using caffeine,

tobacco, or cocaine may increase the risk of bruxism.

Trauma to the joint can occur

after a physical blow to the area or as a result of head or neck injury.

Prolonged opening of the mouth during a dental appointment (e.g., third molar

extractions),10 yawning, eating, or even excessive gum chewing can

cause trauma to the TMJ and related muscles.

Behavioral Factors:

Psychological factors that are seen in TMD patients include stress, anxiety,

and depression.11 A recent article suggested that with appropriate

early biopsychosocial intervention, acute TMD patients can be effectively

treated, regardless of the presence or absence of vulnerability to depression

symptomatology.12

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

In patients with

TMD, orofacial pain may be dull or sharp and occurs when the patient swallows,

talks, or chews. Often, the pain originates in the periauricular area;

however, it may radiate to other locations. If the joint is not properly

aligned or not working correctly, the smooth cartilage that allows the joint

to move easily may wear down, resulting in a popping or clicking noise when

the jaw opens and closes. Crepitus, a crackling or crushing noise, occurs in

more severe cases. The patient often has limited jaw-opening ability. There

may be tenderness to palpation of the TMJ via the external auditory meatus.

The adjacent muscles of the face and jaws are often in spasm, with pain and

tenderness felt in the temple area, cheek, mandible, and teeth. Patients with

TMD have similar symptoms to those of patients with other chronic pain

conditions, such as headache, toothache, earache, tinnitus, neck pain, and

other types of facial pain.13

Clinical Evaluation and

Diagnosis

Due to the

multifactorial nature of TMD, establishing a diagnosis of is difficult.

Although TMDs are a chief source of chronic orofacial pain, other etiologies

must be considered, including neoplasm, aneurysm, migraine, sinus problems,

tooth pathology (e.g., impacted wisdom tooth), nerve damage, and vascular

arteritis.

Clinical examination of the

patient involves evaluation of the range of mandibular movement by recording

the maximum mouth opening (from lower to upper front teeth) using a ruler or

caliper. If the measurement is less than 40 mm or if less than three fingers

fit in the mouth, then the patient has a decreased range of motion, which is

usually accompanied by pain and discomfort. Additionally, bilateral

auscultation of TMJ noises and gentle digital palpation of the joints and

masticatory muscles (i.e., temporalis anterior, masseter, pterygoideus

internus) should be performed.14 Any tenderness or pain in the

joints and/or muscles and joint noises (i.e., clicking or crepitus when the

patient opens and closes the mouth) should be recorded.

Magnetic resonance imaging

(MRI) or computed tomography (CT) scan of the TMJ and orofacial structures may

be performed to rule out other conditions, such as arthritis or a tumor.15

However, radiographs are sometimes difficult to interpret.

A dental examination should be

performed to detect any teeth malocclusion (e.g., crossbite). A complete

patient history should include a review of any oral habits (e.g., bruxism,

clenching, nail biting). Evaluation of the occlusal (top) surface of teeth

will determine if the patient has occlusal wear indicative of bruxism or

clenching.

In patients with chronic TMD,

behavioral, social, and emotional assessments should be performed.

Treatment

Many individuals

undergo various expensive and unproven treatments that may not be effective.

TMDs are often self-limiting and do not progress. However, in some patients

the TMJ undergoes continued degeneration, with a worsening of symptoms. Since

the primary focus of pain is around the ear, the individual may first visit an

ear, nose, and throat physician or otolaryngologist. Having eliminated the

possibility of headache, ear, or sinus problems, the next step is to consider

the possibility of TMJ pain and dysfunction. The dentist should be the next

health care provider that the individual seeks.

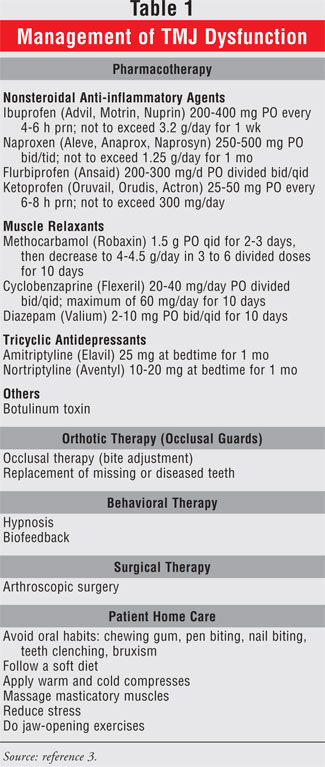

Management of TMJ dysfunction

may involve the use of medications or other nonsurgical or surgical options (

TABLE 1).

Pharmacotherapy:

In patients presenting with acute joint and muscle pain for less than three

months, treatment should be aimed at a reduction of inflammation and pain

using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)† and muscle relaxants.

3 Due to the ulcergoenic potential of NSAIDs, however, not all patients

are good candidates. Patients presenting with chronic pain, along with anxiety

or depression, may require antidepressants or anxiolytics.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory

agents are the first line of treatment to reduce inflammation and pain.

Duration of therapy should be about two to four weeks. Benzodiazepines are

prescribed for significant muscle pain or spasm. Tricyclic antidepressants in

low dosages may reduce pain and nighttime bruxism. However, there have been

reports that antidepressants may trigger bruxism in nonbruxers.16

One of the newest treatment

options for TMJ-induced muscle spasms is injection of botulinum toxin.17

Botulinum toxin is a neurotoxic protein produced by the bacterium

Clostridium botulinum. When botulinum toxin A (Botox) is

injected in minute doses (15 units) into the affected muscles around the TMJ,

acetylcholine released from nerve terminals is inhibited, thus blocking

neuromuscular transmission and rendering the muscle unable to contract. It

takes about 24 to 72 hours after an injection for clinical effects to be seen.

Unfortunately, this amelioration usually lasts for only three to four months,

so most patients require repeated injections over many years. Long-term

effects of this therapy have not been studied.

Behavioral Therapy:

Reduction in stress, anxiety, and depression using behavioral modification

(e.g., relaxation therapy, hypnosis, biofeedback, meditation) and counseling

is an important part of treatment.

Occlusal Therapy:

The primary concern is to rest the muscles and joints. Individuals are

informed to eat soft foods and not to chew gum. To help reduce the incidence

of bruxism and clenching, the dentist may fabricate a soft or hard acrylic

bite plate (also referred to as an occlusal guard, night guard,

or orthopedic appliance) that is placed on the maxillary

(upper) teeth.18 This appliance is worn at night and helps prevent

the teeth from occluding, thus resting on the joint and reducing wear and

tear.

Surgical Therapy:

Arthroscopic surgery may be effective in improving the range of mandibular

movement and pain reduction, but it is mainly performed in patients with

severe joint problems.

Arthrocentesis is a surgical

procedure that washes the upper compartment of the TMJ using saline injections

into the joint space. The fluid is then withdrawn and a second injection

lavages the joint. Corticosteroids can then be injected into the joint space.

Home Care: At

home, patients should apply moist heat to the affected area at least twice a

day for no longer than 15 minutes. The various masticatory muscles involved

should be massaged several times a day until the muscle is not painful to

touch.

Other Treatments:

Ultrasonic treatment uses waves that penetrate deeper into the tissue,

increasing blood flow and reducing pain. This procedure should be done on

alternate days for about 10 minutes. Acupuncture and electronic muscle

stimulation are other methods of treatment.

Pharmacist