US Pharm.

2006;11:70-76.

The use of complementary and

alternative medicine (CAM) has drastically increased over the past few years.

In 2002, it was estimated that 62% of all Americans use some form of CAM.1

CAM spending rose 12% to $30 billion in 2001 and accounted for almost 2.5% of

the $1.2 trillion spent in personal health care in the United States.2

People are seeking other health options and are coming to pharmacists to find

answers to their many health questions. One CAM area of interest is the use of

probiotic agents. Consumers use probiotic agents for a variety of disease

states, including antibiotic-associated diarrhea, irritable bowel syndrome,

and atopic eczema. In the U.S., probiotic sales rose to $177 million in 2003,

were estimated at $764 million in 2005, and are expected to rise at an average

annual growth rate of 7.1%, to reach $1.1 billion in 2010.3 This

article focuses on the non–FDA-approved use of probiotics in the treatment of

atopic eczema in children. In addition, this article discusses the recommended

dosage and possible efficacy of probiotic strains.

The idea of using probiotics

is not a new concept. In the early 1900s, Russian scientist Elie Metchnikoff

hypothesized that by increasing fermented milk intake, a person might increase

his or her life span and health. Metchnikoff observed Bulgarian peasants who

lived long, healthy lives and noted their consumption of fermented milk

products. He was convinced that yogurt contained the bacteria necessary to

protect intestines from the damaging impact of pathogens.4 This

hypothesis is based on the effects of the bacteria used to ferment milk, not

the milk itself. In 1908, Metchnikoff won the Nobel Prize for his work in

immunology. His theory that certain bacteria may improve health is still of

major interest today.

Numerous types of bacteria and

yeasts have been studied for their probiotic potential. A probiotic is

defined as viable bacteria that colonizes the intestines and modifies the

intestinal microflora and their metabolic activities. Probiotics are often

referred to as the "friendly bacteria." The name probiotics

literally means "for life." There are preparations of products containing

living, specified microorganisms in adequate numbers. They help restore the

indigenous microflora and exert a health benefit to the host. Probiotics are

found naturally in our intestinal tract and are thought to help stabilize the

gut microflora. These microbes are often delivered as a lyophilized powder in

a capsule or suspended in yogurt or a dairy beverage.5

Origin of Intestinal Flora

The human

intestinal tract is sterile at birth.6 After birth, infants are

exposed to microorganisms, and over time, hundreds of bacteria reside within

the intestinal tract. Exposure to these different types of flora is thought to

depend on the type of delivery (vaginal or surgical), source of nutrition

(bottle or breast), gestational age, other human contact, environment, and the

mother's prenatal dietary intake.7

Regarding type of birth, it is

proposed that infants born vaginally are exposed to intestinal flora via the

birth canal. These infants appear to have a head start on colonization of

intestinal flora. Babies born by cesarean do not pass through the birth canal

and are believed to have delayed colonization of these organisms.6

Studies have shown that breast-fed infants have higher concentrations of

microflora in the first weeks of life, whereas formula-fed infants have much

fewer of these organisms.6

Once intestinal flora is

established, it is relatively stable throughout life. Some temporary

alterations include the induction of antibiotic therapy, radiation therapy,

and chemotherapy.6

The Role of Microflora

The human body

relies on normal microflora for many functions, including metabolizing foods

and certain drugs, absorbing nutrients, and preventing colonization of

pathogenic bacteria.7 The adult body contains 1 x 1014 cells,

of which 90% are accounted for by members of the microflora.5 These

microflora are considered the first line of defense against invasion by

pathogenic organisms. Sufficient colonization of microflora has been shown to

be an extremely effective natural barrier against pathogens such as Clostridium

difficile, Salmonella, Shigella, Pseudomonas, Escherichia coli, and

Candida albicans. Probiotics are the most effective against conditions

that are linked to the underlying disruption of this protective normal

microflora barrier (e.g., due to broad-spectrum antibiotics, travel, stress,

and changes in nutrition).5

Probiotic Strains

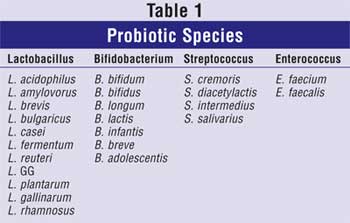

The most commonly used probiotic

preparations are those derived from the lactic acid bacteria (Lactobacillus).

These organisms are found in large numbers in the intestines of healthy

animals.4 Bifidobacterium strains are also probiotic species

typically consumed (Table 1). Other organisms currently available

include bacilli, yeasts, and filamentous fungi. These products are

commercially supplied in the form of powders, capsules, wafers, tablets,

pastes, and sprays.

Prevalence of Eczema

Eczema is

subdivided into atopic and nonatopic eczema.8 Atopic

eczema is a group of diseases involving inflammation of the skin with intense

itching, reddening, dryness, blistering, and scaling.9 The disease

most commonly begins early in infancy and childhood. Infants are prone to

weeping inflammatory patches and crusted areas on the face, neck, extensor

surfaces, and groin.10 The prevalence of atopic eczema varies

between countries. It is estimated that fewer than 2% of children in China and

Iran exhibit atopic eczema, but as many as 20% of children in northern and

western Europe, Australia, and the U.S. exhibit atopic eczema.8

With the incidence of atopic disease rising in Western countries, data have

indicated early immune dysregulation in the infant gut and disruption of the

establishment of normal, healthy gut microflora.11

Why are so many children

affected with eczema? In 1989, Strachan hypothesized that infections in early

childhood acquired from older siblings might confer protection against atopic

diseases, such as atopic eczema.12 This theory became known as the hygiene

hypothesis and suggests that environmental changes in the industrialized

world have led to reduced microbial contact at an early age. Rautava and

colleagues have further studied this topic and concluded that an extended

hygiene hypothesis implies that the epidemic of atopic disease is a result of

altered living conditions and improved hygiene, which are causing drastic

changes in factors affecting the initial establishment of indigenous

intestinal microbiota.12

Clinical Evaluation of

Eczema

In order to evaluate the severity of

atopic disease as objectively as possible, the European Task Force on Atopic

Dermatitis developed a method designed for consistent assessment via an index

called SCORAD (severity scoring of atopic dermatitis). The SCORAD index

was developed in 1993 and evaluates five clinical signs: erythema,

vesiculation, excoriation, crusting, and edema. Each of these signs has four

scoring points, ranging from 0 to 3: 0 = absent; 1 = mild; 2 = moderate; 3 =

severe. The score is determined based on several criteria relating to lesion

spread and intensity, as well as subjective signs. Many clinical trials use

the SCORAD index changes as their end point to evaluate treatment efficacy.

Proposed Mechanism of

Action of Probiotics

Most clinical

studies have shown that probiotics can reduce symptoms in pediatric patients.11

The rationale for its use is based on the potential effects of friendly

bacteria on cellular immune responses. T cells--white blood cells derived from

the thymus gland--fight infection and participate in a variety of cell-mediated

immune reactions. The two main types of T cells are killer (or

cytotoxic), which can kill tumor- and virus-infected cells, and helper,

which provide help to killer T cells, B cells, and macrophages. T helper cells

have a major role in the adaptive immune response. T helper cells are divided

into two subtypes: TH1 and TH2. The TH1

subtype targets organisms that get inside our cells, known as cell-mediated

immunity. The TH2 subtype attacks organisms found outside the

cells in blood and other bodily fluids, known as antibody-mediated immunity.

Accumulating evidence indicates that the overreactivity of TH2

responses is associated with atopic disease.12 It has been

speculated that exposing infants to friendly bacteria early in life helps

mature the TH1 cell immune response and could inhibit development

of the TH2 allergic response, thus decreasing the risk of atopic

disease.13

Healthy microflora in the

intestines may serve as a mucosal barrier against invading organisms.14

It has been proposed that atopic children have an impairment in the

development of their normal gut mucosal barrier. This disruption may lead to

increased antigen transport and high-level antigen exposure during the first

few months of life, which predisposes them to allergic sensitization, thus

resulting in atopic disease.11 Some probiotic strains may

strengthen the lining of the intestines and prevent antigen transport,

decreasing the occurrence of atopic disease. It is also important to note that

stress, illness, antibiotic treatment, changes in diet, or physiological

alterations in the gut may cause the integrity of the microflora to become

impaired.5 Using probiotic agents during stressful times may also

help to maintain intestinal integrity.

Literature suggests that

probiotics help reinforce different lines of gut defense by competing with

pathogens for binding and receptor sites. This is thought to enhance host

resistance to pathogens and aid in their eradication.15 In

addition, probiotics are believed to stimulate production of compounds that

inhibit or destroy pathogens.6

Clinical Trials

Treatment of

Eczema: Several

studies have been conducted regarding the use of probiotics in the treatment

of eczema. One study involved 56 children ages 6 to 18 months with moderate or

severe atopic eczema who participated in a randomized, double-blind,

placebo-controlled trial.15 Children were given a probiotic (1 x 109

Lactobacillus fermentum PCC) or placebo for eight weeks. At the end of

the study, outcomes were measured by the SCORAD index. The reduction in the

SCORAD index over time was significant in the probiotic group (P = .03)

but not in the placebo group. This study concluded that providing

supplementation with probiotic L. fermentum PCC is beneficial in

improving the extent and severity of atopic eczema in young children with

moderate or severe disease.15 This study also concluded that the

positive effects of probiotic supplementation were apparent two months after

supplementation was ceased.15

Another randomized study

assessed the potential of probiotics to control allergic inflammation at an

early age.16 Twenty-seven infants (mean age, 4.6 months) who

exhibited atopic eczema were weaned from breast-feeding and were either given

extensively hydrolyzed whey formulas that were probiotic supplemented with Bifidobacterium

lactis Bb12 or L. GG (LGG) strain or were given the same formula

without probiotics. After eight weeks, a significant improvement in skin

condition was seen in infants given probiotic-supplemented formulas, compared

to the unsupplemented group.16 These data further indicate the

effect probiotics may have on the inflammatory responses.

In a double-blind,

placebo-controlled, crossover study, two probiotic Lactobacillus

strains (L. rhamnosus and L. reuteri) were given in combination

for six weeks to children ages 1 to 13 years with atopic eczema.17

The clinical severity of atopic eczema was evaluated by using the SCORAD

index. Eosinophil cationic proteins in serum and cytokine production were also

measured as inflammatory markers. To assess allergic sensitization, patients

were given a skin prick test. Those who had a positive skin prick test

response and increased IgE levels were classified as allergic patients.

After active probiotic treatment, 56% of the patients experienced improvement

of their eczema, compared to 15% in the placebo group. Although the overall

SCORAD index did not change significantly, the treatment response was more

profound in allergic patients. Thus, the study concluded that a combination of L.

rhamnosus and L. reuteri was beneficial in the management of atopic

eczema.17

Prevention of Eczema:

A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial was performed to examine

the occurrence of atopic eczema in infants. Mothers who had at least one

first-degree relative (or partner) with atopic eczema, allergic rhinitis, or

asthma were given LGG prenatally. LGG was also given to the infants

postnatally for six months.18 After two years, atopic eczema was

diagnosed in 46 of the 132 (35%) children. The frequency of atopic eczema in

the probiotic group was half that in the placebo group. A follow-up study

after four years showed that 14 of 53 children receiving LGG had developed

atopic eczema, compared to 25 of 54 receiving placebo. Thus, the preventive

effect of LGG on atopic eczema in at-risk children extends to the age of 4

years.18

Safety

To assess the

safety of probiotic ingestion, a randomized double-blind study was conducted

in 118 infants.19 This study evaluated tolerance, effects on

growth, clinical status, and intestinal health. Infants were divided into

three groups. Group A received 1 x 106 colony-forming units (cfu)/g

of B. lactis and Streptococcus thermophilus. Group B received 1

x 107 cfu/g of B. lactis and S. thermophilus. Group C

was an unsupplemented group. Results demonstrated that the supplemented

formulas were well accepted by the infants. Statistically significant

decreases were seen in frequency of colic or irritability (P < .001)

and antibiotic use (P < .001). The study found no difference in growth,

day-care absenteeism, or other health variables. Probiotic use was deemed well

tolerated and safe for infants.19

Probiotic safety has not been

a major area for concern, since fermented foods are often used in our diet.

Probiotic species have been used in food processing for years. In fermented

foods, probiotic bacteria helps produce flavor compounds, such as yogurt and

cheese, improves the nutritional value of food, as in the release of free

amino acids or the synthesis of vitamins, and preserves milk with the

generation of lactic acid and possible antimicrobial compounds.4

There is a long history of safety with probiotic use.

Adverse Effects

Most large clinical studies have not

found any serious problems with probiotic ingestion. In one case, a person

taking LGG developed a liver abscess that was caused by a probiotic strain.

Patients who have suffered complications due to probiotic strains were more

likely to have severe comorbidities or surgeries or were immunosuppressed.

Rare case reports have identified probiotic-related bacteremia and fungemia in

patients with underlying immune compromise, chronic disease, or debilitation.

There have been no reports of bacteremia or fungemia sepsis related to

probiotic use in otherwise healthy people. Most cases linked to probiotic

sepsis have been resolved with appropriate antimicrobial therapy.20

Contraindications include allergies to bacteria or yeast products.

Patient Counseling

Recommended daily

intake for probiotic supplements ranges from one billion units (sometimes

referred to as cfu) to 10 billion units per day.21 These

amounts may be seen on the label as 1 x 109 or 109 for

one billion units and 1 x 1010 or 1010 for 10 billion

units. No specific dosing guidelines are available for children, but most

clinical trials of atopic eczema in children contained probiotic doses ranging

from 1 x 106 to 1 x 1010 cfu/day. In Europe, some infant

formulas contain probiotics. The dose in these formulas can be as high as 1010

cfu/day. When taking antibiotics, it is advisable to take probiotics at least

two hours apart from an antibiotic. The antibiotic could recognize the

probiotic as bacteria and kill the organism. Although not a requirement,

refrigerating probiotic products help prolong their shelf-life.21

Summary

The prevalence of

atopic disease has increased over the past few decades, particularly in

Western societies. Recent research points to early immune dysregulation in the

intestines of infants and the disruption of normal, healthy gut microflora

establishment. Managing atopic eczema in children can be extremely frustrating

for both the parent and child. Treatment options are often expensive and

inconvenient. The growing interest in using probiotic treatment brings hope to

many patients suffering from this disorder. Evidence supports the use of

probiotics for the treatment of atopic eczema, as well as prenatally aiding in

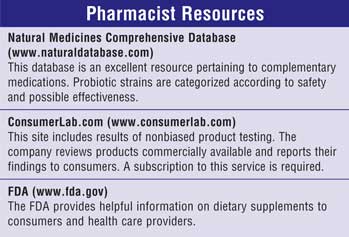

prevention of the disease. Pharmacists should keep in mind that probiotics are

considered a food supplement and are not regulated by the FDA. Finding a

respectable manufacturer is of utmost importance when considering probiotic

formulations. Some Internet resources can provide guidance to unbiased testing

of products currently on the market. Clinical evidence suggests that probiotic

strains appear safe but should probably be avoided in patients who are

immunocompromised. As with any product, pharmacists should consider proper

dosages, storage, and the expiration date when recommending probiotic products

to their patients.

References

1. The Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine in the United States. Available at: www.nccam.nih.gov/news/camsurvey_fs1.htm. Accessed June 20, 2006.

2. Naturopathic Medicine. CAM Spending. Available at: www.aanmc.org/nat_med/healthcare.php#spending. Accessed June 20, 2006.

3. Probiotics: Ingredients, Supplements, Foods. Available at: www.bccresearch.com. Accessed June 20, 2006.

4. Parvez S, Malik KA, Ah Kang S, Kim HY. Probiotics and their fermented food products are beneficial for health. J Applied Microbiol. 2006;100:1171-1185.

5. Probiotics. Available at: www.freece.com. Accessed May 26, 2006.

6. Young R, Huffman S, et al. Probiotic use in children. J Pediatr Health Care. 2003;17:277-283.

7. Lactobacillus. Available at www.naturaldatabase.com. Accessed October 14, 2005.

8. Brown S, Reynolds NJ. Atopic and non-atopic eczema. BMJ. 2006;332:584-588.

9. The Atopic Eczema/Dermatitis Syndrome. Available at: www.worldallergy.org. Accessed May 30, 2006.

10. Cookson WO, Moffatt MF. The genetics of atopic dermatitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;2:383-387.

11. Ogden NS, Bielory L. Probiotics: a complementary approach in the treatment and prevention of pediatric atopic disease. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;5:179-184.

12. Rautava S, Ruuskanen O, Ouwehand A, et al. The hygiene hypothesis of atopic disease–an extended version. J Pediatric Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;38:389-388.

13. Murch SH. Probiotics as mainstream allergy therapy? Arch Dis Child. 2005;90;881-882.

14. Macfarlane GT, Cummings JH. Probiotics and prebiotics: can regulating the activities of intestinal bacteria benefit health? BMJ. 1999;318:999-1003.

15. Elmer GW. Probiotics: ‘living drugs.' Am J Health-Systems Pharm. 2001;58:1101-1109.

16. Isolauri E, Arvola T, Sutas Y, et al. Probiotics in the management of atopic eczema. Clin Exp Allergy. 2000;30:1604-1610.

17. Rosenfeldt V, Benfeldt E, Nielsen SD, et al. Effect of probiotic Lactobacillus strains in children with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:389-395.

18. Kalliomaki M, Salminen S, Poussa T, et al. Probioitcs and prevention of atopic disease: 4-year follow-up of a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361:1869-1871.

19. Saavedra J, Abi-Hanna A, Moore N, et al. Long-term consumption of infant formulas containing live probiotic bacteria: tolerance and safety. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:261-267.

20. Boyle RJ, Robins-Browne RM, Tang ML. Probiotic use in clinical practice: what are the risks? Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:1256-1264.

21. Product Review: Probiotic

Supplements and Foods. Available at: www.consumerlab.

com.

Accessed September 8, 2005.

To comment on this article,

contact editor@uspharmacist.com.