US Pharm. 2007;32(9):45-53.

Rosacea

is a common, chronic skin disorder characterized by transient or persistent

central facial erythema, telangiectasia (visible blood vessels), inflammatory

episodes with papules and pustules, and, in severe cases, rhinophyma.

1,2 It is estimated that approximately 14 million people in the United

States are diagnosed with some form of this dermatosis. Rosacea most

frequently occurs in people between the ages of 30 and 50 years, with women at

two to three times greater risk than men. Northern European descendants are at

greatest risk for developing this condition.2

The National Rosacea Society

Expert Committee developed a standard classification system based on the

morphologic characteristics of the condition. The system identifies the

primary and secondary signs and symptoms of rosacea.3 Primary signs

and symptoms include transient erythema, nontransient erythema, papules,

pustules, and telangiectases.3 If one or more of the primary signs

concomitantly occur with central face distribution, rosacea is suspected.

Patients who are diagnosed with rosacea and exhibit one or more of the primary

features often present with the secondary signs and symptoms. These include

burning or stinging, plaques, dry appearance, edema, ocular manifestations,

and phymatous changes. Secondary features usually appear in the presence of

the primary symptoms but can also occur in the absence of primary signs and

symptoms.3 Due to the various and numerous manifestations of the

disease, the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee has created subtypes of

the condition.

Classification

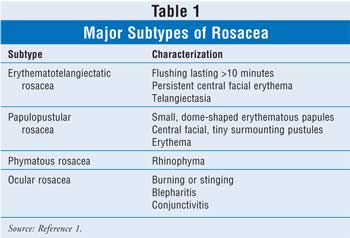

There are four

major subtypes and several other nonclassic subtypes that describe the most

common patterns associated with the signs and symptoms of rosacea. The

subtypes include erythematotelangiectatic rosacea (ETR), papulopustular

rosacea (PPR), phymatous rosacea, and ocular rosacea (TABLE 1).1

ETR is the most common subtype and is characterized by flushing, which

usually lasts longer than 10 minutes, accompanied by persistent central facial

erythema. Telangiectasia is usually prominent on the cheeks and nose in

patients with the ETR subtype and may contribute to erythema. This subtype of

rosacea responds poorly to treatment.1 PPR typically presents as

small, dome-shaped erythematous papules with tiny surmounting pustules on the

central portion of the face. This subtype, which is fairly uncommon, is also

associated with erythema and telangiectatic vessels.1 The most

frequent manifestation of this subtype is rhinophyma. Rhinophyma can be a

disfiguring condition of the nose that results from hyperplasia of both the

sebaceous glands and the connective tissue. Although rosacea is more frequent

among women, rhinophyma is predominant among men, with the ratio being

approximately 20:1.1 The last subtype, ocular rosacea, is common

but often misdiagnosed. This type of rosacea can manifest as blepharitis and

conjunctivitis with inflamed eyelids and meibomian glands; however, most

patients present with mild symptoms, such as burning or stinging in the eye.

This may precede, follow, or occur simultaneously with other classic rosacea

symptoms.1

Other nonclassic subtypes of

rosacea include glandular rosacea and granulomatous rosacea. Glandular rosacea

is characterized by thick, sebaceous skin; papules and pustules; and

nodulocystic lesions. Granulomatous rosacea is described as the presence of

yellow, brown, or red papules or lesions on the cheeks or around the mouth and

eyes. Granulomatous rosacea may be classified as granulomatous facial

dermatitis rather than a type of rosacea, because these patients do not have

persistent erythema and usually present with lesions outside the central face

or with disease in a unilateral distribution. Such patients are less likely to

have the flushing, burning, and stinging characteristic of other subtypes.

1

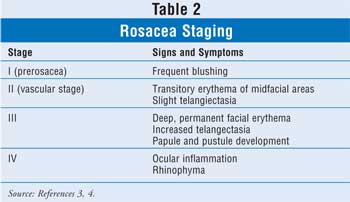

The development of rosacea

occurs in four stages (TABLE 2). Stage I is described as prerosacea. In

this stage, rosacea-induced blushing is the main symptom and can develop as

early as childhood. Stage II is mainly vascular; the disease progresses into

transitory erythema of the midfacial area, and mild telangiectasia begins to

develop. During stage III, facial redness worsens, becoming deeper and

permanent. Also during this stage, telangiectasia increases, ocular changes

begin to develop, and papule and pustule formation occurs. In stage IV, there

is continued and increased skin and ocular inflammation. The ocular

inflammation can ultimately result in visual loss. It is also in this stage

that fibroplasia and sebaceous hyperplasia of the skin lead to rhinophyma.

4

Etiology

The exact etiology

of rosacea remains unknown; however, several factors have been implicated in

its pathogenesis.1-2,4 The erythema is caused by dilation of the

superfacial vasculature of the face. This increased blood flow to the

superfacial vasculature results in edema. It has been proposed that

Helicobacter pylori may be a cause of this disease.4 Recent

studies have also linked H pylori with urticaria, Schonlein-Henoch

purpura, and Sjogren's syndrome. It remains controversial whether there is

benefit from the eradication of H pylori on the symptoms associated

with rosacea.4 Other possible etiologies include climatic exposure,

ingested chemical agents, abnormalities in cutaneous vascular homeostasis,

endothelial damage and matrix degeneration of the skin, and microbial

organisms (e.g., Demodex folliculorum).1,4

Prior to initiating treatment,

factors that trigger signs and symptoms should be identified and, if possible,

avoided. Triggers are patient-specific; however, the most common known

triggers include hot or cold temperatures, wind, hot drinks, exercise, spicy

food, alcohol, emotional stress, topical products, menopausal flushing, and

medications that may induce flushing (i.e., niacin, disulfiram, nitroglycerin).

5,6 Some important preventive measures that patients with rosacea can

take include the daily use of a gentle sunscreen, avoidance of midday sun, and

the use of protective clothing.5,6 Alcohol consumption is not known

to be a direct cause of the disease, but it can aggravate the condition

through peripheral vasodilation.5 Only hypoallergenic and

nonirritating facial cleansers, lotions, and cosmetics should be used in these

patients.4,5

Cure Still Elusive

The cure for

rosacea remains elusive, and all of the medications currently used will only

help in resolving symptoms but will not completely eradicate the disease.

Therefore, the goal in managing rosacea is to control the symptoms as opposed

to eradicating the disease. Rosacea should be treated within the

early stages to prevent progression to edema and irreversible fibrosis.

Treatment typically depends on the subtype and stage of rosacea.1,4

Both topical and oral medications are used in the treatment of rosacea, and

those agents most commonly prescribed include topical metronidazole, sodium

sulfacetamide–sulfur cleanser, azelaic acid, and oral tetracycline and

macrolide antibiotics. When treating rosacea, therapy should be initiated with

a combination of both oral and topical products, as this regimen has been

shown to reduce the initial prominent symptoms, prevent relapse when oral

therapy is discontinued, and maintain long-term control. Oral therapy is

usually continued until inflammation dissipates or for a maximum of 12

weeks--whichever comes first. Antibiotics have traditionally been considered

first-line therapy, primarily due to their anti-inflammatory effects as

opposed to their antimicrobial action alone.4 The tetracyclines and

macrolides are the most commonly prescribed antibiotics for the treatment of

rosacea.

Topical Treatments

To date, there are

only three FDA-approved topical medications for the treatment of rosacea,

particularly for the management of papules, pustules, and erythema. The three

approved topical medications include 0.75% and 1% metronidazole, 10% sodium

sulfacetamide with 5% sulfur, and 15% azelaic acid gel. Other medications that

are not FDA approved for the treatment of rosacea but have shown some

beneficial effects include benzoyl peroxide, clindamycin, retinoids, and

topical steroids.5,6

Several randomized, double-blind,

placebo-controlled trials involving the use of topical metronidazole have

indicated that it is safe and effective in the treatment of rosacea.7-12

The pharmacologic mechanism responsible for the effectiveness of

metronidazole in the treatment of rosacea remains unclear; however, in

vitro studies have shown that metronidazole interferes with the release of

reactive oxygen species from neutrophils that cause tissue injury at the site

of inflammation.13 Clinical trials suggest that topical

metronidazole is most effective at reducing inflammatory lesions and erythema

associated with rosacea.14 In addition, one of the other benefits

to using topical metronidazole is the lack of systemic toxicity that is noted

with the oral formulation.13 Although it is generally used as

first-line treatment and continues to be one of the most widely prescribed

medications in the treatment of rosacea, the optimal dose of metronidazole for

this condition has yet to be determined. Daily dosing and twice-daily dosing

of the 1% and 0.75% formulations, respectively, have proven to be effective

for this condition. Currently, topical metronidazole is available as a

twice-daily application of 0.75% cream or gel and as a once-daily 1% cream.

The 0.75% formulation was originally approved as a twice-daily application

based on its half-life of six hours. However, recent data suggest that

metronidazole is metabolized into active metabolites that may prolong its

efficacy, and once-daily dosing of the 0.75% cream is now regarded as an

acceptable form of treatment.5,13 The effectiveness of the

once-daily 0.75% formulation was found to be equivalent to the once-daily 1%

formulation in a 12-week, randomized trial that included 72 patients. No

significant difference existed between the treatment groups with regard to

reduction of erythema, papules, and pustules; treatment failure; dryness;

safety; and global assessment of severity.12

Topical metronidazole has

shown to reach significant reduction of erythema as early as week 2 and as

late as week 10 depending on the formulation.10,11 In a

double-blind, randomized clinical trial, the 1% formulation significantly

reduced inflammatory lesions by week 4.10 Maintenance therapy is a

critical aspect of rosacea therapy. Typically, after discontinuing treatment,

relapse occurs in one fourth of patients after one month and in two thirds of

patients after six months.14 In a randomized, double-blind,

placebo-controlled clinical trial, topical metronidazole effectively

maintained remission over six months in those patients who were previously

treated with combination therapy including tetracycline and topical

metronidazole.15 After discontinuing oral medication in a

multicenter, randomized, double-blind trial, topical metronidazole maintained

remission longer than placebo, and 23% of patients relapsed with metronidazole

gel compared to 42% with the placebo cream.15,16 Topical

metronidazole is poorly absorbed with either undetectable or trace serum

concentrations reported after its use.13 Topical metronidazole is

generally well tolerated, with adverse events reported in less than 5% of

patients. The most common reactions reported were local reactions including

dryness, redness, pruritis, burning, and stinging.13

The combination of sodium

sulfacetamide 10% and sulfur 5% provides a safe, well-tolerated, and effective

option for the treatment of rosacea that may be less irritating than

metronidazole.4,5 Traditionally, this combination's use was limited

because of its unpleasant odor; however, it is now formulated as a cleanser

with a masked odor. This new formulation has led to the reemergence of this

product.6 The proposed mechanism of action of these agents in the

treatment of rosacea is attributed to the antibacterial properties of

sulfacetamide and its ability to compete with para-aminobenzoic acid along

with the keratolytic properties of sulfur, which is believed to have an

anti-inflammatory effect.17 In an eight-week, double-blind,

placebo-controlled trial, the combination of sulfacetamide and sulfur

decreased inflammatory lesions by 78%, compared to a 36% decrease in the

placebo arm. The sodium sulfacetamide–sulfur combination also decreased

erythema by 83%, compared to a 31% decrease in the placebo group.18

This twice-a-day cleanser is effective as monotherapy and has been shown to

significantly reduce papule count and erythema.19 However, the use

of sodium sulfacetamide-sulfur cleanser followed by metronidazole cream has

proven to be superior to the cleanser alone in reducing papule counts and

overall rosacea severity.19 The newer wash on/wash off sodium

sulfacetamide–sulfur formulation has lower irritation potential, improved

absorption through hydrated skin, less lingering odor, and fewer drug–drug

interactions with other topical regimens or cosmetics.5 Most of the

adverse reactions associated with sodium sulfacetamide-sulfur use are mild and

include pruritis, contact dermatitis, irritation, and xerosis. The combination

of sodium sulfacetamide and sulfur is contraindicated in patients with a

sulfonamide hypersensitivity.20

Azelaic acid 15% gel is the

most recently FDA-approved topical agent for the treatment of rosacea. It is a

naturally occurring saturated dicarboxylic acid similar to metronidazole and

is thought to inhibit the reactive oxygen species produced by neutrophils.

5 The efficacy and safety of azelaic acid gel in PPR was investigated in

two vehicle-controlled, randomized, phase III trials involving 664 subjects.

21 Improvement of erythema occurred in 44% and 46% of patients in the

azelaic acid groups compared to 29% and 28% improvement in the placebo-treated

patients. From baseline, the mean reductions of inflammatory lesions were 58%

and 51% in the azelaic acid–treated groups compared to 40% and 39% in the

control groups. Burning, stinging, or itching was experienced by 38% of the

patients treated with azelaic acid. Scaling, dry skin, and rash occurred in

approximately 12% of the azelaic acid–treated patients. The majority of these

side effects were transient in those affected.21 In a smaller

randomized, double-blind, parallel trial, azelaic acid 15% was compared to

metronidazole gel 0.75% in patients with PPR. Patients received either azelaic

acid or metronidazole twice daily for 15 weeks. Azelaic acid gel was

significantly more effective at reducing inflammatory lesions and the mean

lesion count.22 There was a 72.7% decrease in the inflammatory

lesions in the azelaic acid group compared to a 55.8% decrease in the

metronidazole group. Azelaic acid also significantly improved erythema

severity, as 56% of the patients treated with azelaic acid improved versus 42%

of metronidazole-treated patients.22 There were no serious or

systemic adverse effects reported in either treatment group. However, 26% of

the azelaic acid treatment group experienced facial skin reactions and

symptoms compared to 7% in the metronidazole-treated patients.22

Benzoyl peroxide,

erythromycin, and clindamycin have all been used as topical agents for the

treatment of rosacea; however, none of them has been FDA approved because

there is limited data available to support the use of these topical products

for this disorder; they are only to be used as alternative therapies.5

Benzoyl peroxide is typically used in patients with phymatous and glandular

rosacea. The use of erythromycin for rosacea was prompted by its successful

treatment of acne vulgaris. This twice-daily topical preparation has been

shown to reduce erythema and suppress papules and pustules after four weeks of

treatment.23 Topical clindamycin is primarily used in the treatment

of acne, but it can be an effective alternative to tetracycline and topical

metronidazole in patients with rosacea who are pregnant.5,24,25

Oral Antibiotics

Oral antibiotics

have been a mainstay of rosacea therapy for more than 40 years. They have

proven to be effective in reducing the signs and symptoms associated with this

condition. Historically, rosacea was thought to be a result of a bacterial

infection, and since the 1950s oral antibiotics have been used as off-label

therapy.26 Currently, there is only one FDA-approved antibiotic for

the treatment of rosacea, the tetracycline doxycycline (Oracea). The number of

FDA-approved antibiotics for the treatment of rosacea is limited, primarily

because compelling evidence that the disorder is secondary to a bacterial

infection is lacking. Tetracycline and its derivatives minocycline and

doxycycline are the principal oral antibiotics of choice for the treatment of

rosacea.26 The tetracyclines have the ability to down-regulate

production of proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1 and tumor

necrosis factor alpha. They also inhibit proteolytic enzymes produced by

inflammatory cells that degrade collagen, thereby decreasing inflammation that

is seen during the inflammatory response in rosacea.26

Tetracyclines are most effective against PPR; however, relapse rates are high

if they are used as monotherapy without a topical agent.24,26

Traditionally, tetracycline 250 to 1,000 mg daily and doxycycline or

minocycline 100 to 200 mg daily for three to four weeks have been the most

common dosages used to achieve substantial improvement in the signs and

symptoms.26

In May 2006, the FDA approved

doxycycline (Oracea) 40 mg once daily, the first oral medication approved for

the treatment of rosacea. It is only indicated for the treatment of

inflammatory lesions (papules and pustules) in adult patients.28 To

date, there have been two phase III clinical trials involving doxycycline.

Both of these studies were double-blind, placebo-controlled trials and were

conducted simultaneously. A total of 537 patients received either placebo or

doxycycline 40 mg once daily for 16 weeks. In both studies, doxycycline

significantly reduced inflammatory lesions compared to placebo. In the two

studies, the doxycycline-treated patients had a mean reduction in inflammatory

lesion count of 61% and 46% compared with 29% and 20% in those who received

placebo.29 There are also data supporting the use of doxycycline 20

mg twice daily in those patients with inflammatory lesions and erythema.

5,27 The twice-a-day regimen is believed to have fewer adverse reactions

and is less likely to cause bacterial resistance because it results in

subantimicrobial blood levels.26 Minocycline and doxycycline have

longer elimination half-lives and improved bioavailability compared to the

parent compound, which can prolong their duration of action and minimize

gastrointestinal (GI) side effects.5 Possible adverse reactions

that may occur with the use of tetracycline include GI irritation, rash, renal

toxicity, hepatic cholestasis, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and hypersensitivity

reactions. The tetracyclines are contraindicated in pregnancy and in children

younger than 8 years.30

The oral macrolides

erythromycin, clarithromycin, and azithromycin have been used for the

treatment of PPR.26 The macrolides prevent bacterial growth by

interfering with protein synthesis. They inhibit the translocation of peptides

by binding to 50S of the bacterial ribosome. These antibiotics are most

commonly used when intolerance, pregnancy, resistance, or allergies prevent

the use of tetracyclines.5 One advantage of the use of the

second-generation macrolides clarithromycin and azithromycin over erythromycin

is that they have a faster onset of action and less GI irritation than

erythromycin.31,32 Clarithromycin 250 to 500 mg twice daily for six

weeks has been found to be as effective as doxycycline with a more tolerable

side-effect profile.31 In a trial that compared clarithromycin 250

mg twice daily for four weeks followed by clarithromycin 250 mg once daily for

four weeks to doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for four weeks followed by

doxycycline 100 mg daily for four weeks, clarithromycin reduced erythema and

papules at a faster rate. The authors concluded that six weeks of

clarithromycin treatment was as efficacious as eight weeks of doxycline

treatment.31 Azithromycin 250 mg for 12 weeks proved to decrease

inflammatory lesions by 89% from baseline.32 Clarithromycin and

azithromycin are preferred over erythromycin because of better tolerance and

improved bioavailability; however, these second-generation macrolides may be

more expensive.26 Larger, controlled clinical trials are necessary

to determine the exact role of the second-generation macrolides in both

initial and maintenance therapy for rosacea.

Oral metronidazole may serve

as another alternative for those who cannot tolerate tetracyclines or for

those who have been treated unsuccessfully with tetracycline. A double-blind,

randomized trial evaluated the efficacy of oral metronidazole in rosacea

treatment. Patients received oral metronidazole 200 mg twice daily or

oxytetracyline 250 mg twice daily. Both therapies showed sustained improvement

at 12 weeks.5

In some patients, isotretinoin

can be used for refractory rosacea, as it reduces the size of sebaceous glands

and alters keratinization. Small clinical trials have demonstrated that

isotretinoin may reduce the number of papules and pustules, erythema, and

nasal volume in rhinophyma in patients with refractory rosacea.5

More recently, Erdogan et al. evaluated low-dose isotretinoin 10 mg daily for

four months in patients with treatment-resistant rosacea.33

Isotretinoin significantly reduced inflammatory lesions, erythema, and

telangiectasia. Use of isotretinoin is often limited due to its serious and

abundant side-effect profile. The most common adverse effects include bone or

joint pain, burning, redness, itching, eye inflammation, nosebleeds,

scaling, skin infection, and rash. Isotretinoin is contraindicated in

pregnancy, as it is teratogenic; for this reason, it has to be prescribed

under a special restricted distribution program.34 Information

regarding isotretinoin's optimal dosage and duration of therapy for the

treatment of rosacea is limited. In addition, the majority of the clinical

trials evaluating its safety and efficacy involve small sample sizes.

Therefore, more studies involving larger patient populations are needed to

determine the optimal dosage and duration of therapy.

Laser and Light Therapies

Vascular laser therapy and light

therapy serve as additional options for the treatment of telangiectasia in

patients who do not respond to conventional therapy. Laser and light therapy

have the capability to reorganize and remodel dystrophic dermal connective

tissue and strengthen the epidermal barrier by thermally inducing fibroblasts

and endothelial proliferation or by causing endothelial disruption, leading to

cytokine, growth factor, and heat shock protein activation.35 The

vascular laser therapies currently used for telangiectasia and erythema are

the standard pulse-dye laser (585 or 595 nm), long pulsed-dye lasers (595 nm),

the potassium titanyl phosphate laser (532 nm), and the diode-pumped

frequency-doubled laser (532 nm). The short-wavelength lasers (541 and 577 nm)

induce vessel destruction without causing collateral tissue damage.35

Therefore, the short-wavelength vascular lasers are preferred for superficial

red vessels and persistent erythema. Intense pulsed-light therapy penetrates

the skin deeper than vascular laser therapy and is best suited for vascular

lesions and pigmented lesions. Its main benefits are the ability to treat

larger and deeper vessels and promote collagen remodeling. Laser and light

therapies may require one to three treatments four to eight weeks apart to

achieve the best results; however, their use is limited due to cost.35,36

Summary and Conclusion

Currently, rosacea

treatment is aimed at reducing symptoms and improving facial appearance. Many

questions still remain regarding the pathogenesis and etiology of the disease.

Even though a definitive cause has not been determined, therapy should begin

with avoiding possible triggers. If a patient is still experiencing rosacea

symptoms once triggers have been identified and, if possible, removed, topical

metronidazole remains the first-line therapy for the treatment of rosacea.

Other topical agents such as sodium sulfacetamide–sulfur combination, azelaic

acid, benzoyl peroxide, erythromycin, and clindamycin can be used as an

alternative to metronidazole. Oral antibiotics, which can prevent relapse and

maintain remission, are often used in combination with the topical agents.

Recently, the first oral antibiotic, doxycycline, was FDA approved for the

treatment of inflammatory lesions associated with rosacea. If topical and oral

treatments are unsuccessful, vascular laser and light therapies are options

for refractory cases.

Even though there are a

variety of therapeutic options for the treatment of rosacea, investigation of

genetic factors and the histologic and pathologic basis of papules and

pustules still need to be carried out; this will lead to new and improved

treatment options and may help decrease psychosocial distress of affected

individuals. Despite the lack of understanding, therapy has improved since the

diagnostic criteria have become more uniform.

References

1. Crawford G,

Pelle M, James W. Rosacea: I. Etiology, pathogenesis, and subtype

classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:327-341.

2. Fernandez A. Oral

use of azithromycin for the treatment of rosacea. Arch Dermatol.

2004;140:489-490.

3. Wilkin J, Dahl M,

Detmar M, et al. Standard grading system for rosacea: Report of the national

rosacea society expert committee on the classification and staging of rosacea.

J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:907-912.

4. Cohen A, Tiemstra J.

Diagnosis and treatment of rosacea. J Am Board Fam Pract.

2002;15:214-217.

5. Pelle M, Crawford G,

James W. Rosacea: II. Therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:499-512.

6. Nally J, Berson D.

Topical therapies for rosacea. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:23-27.

7. Nielsen PG. A double

blind study of 1% metronidazole cream versus systemic oxytetracycline therapy

for rosacea. Br J Dermatol. 1983;109:63-65.

8. Nielsen PG.

Treatment of rosacea with 1% metronidazole cream. A double blind study. Br

J Dermatol. 1983;108:327-332.

9. Bleicher PA, Charles

JH, Sober AJ. Topical metronidazole therapy for rosacea. Arch Dermatol.

1987;123:609-614.

10. Breneman D, Stewart

D, Hevia O, et al. A double-blind, multicenter clinical trial comparing

efficacy of once daily metronidazole 1% to vehicle in patients with rosacea.

Cutis. 1998;61:44-47.

11. Jorizzo J, Lebwohl

M, Tobey R. The efficacy of metranidazole 1% cream once daily compared with

metronidazole 1% twice daily and their vehicles in rosacea: a double blind

clinical trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:502-504.

12. Dahl M, Jarratt M,

Kaplan D, et al. Once daily topical metronidazole cream formulations in the

treatment of papules and pustules of rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol.

2001;45:723-730.

13. Zip C. An update on

the role of topical metronidazole in rosacea. Skin Therapy Lett.

2006;11:1-4.

14. Del Rosso J.

Topical therapy for rosacea: a status report. Practical Dermatology.

2004:43-46.

15. Dahl MV, Katz HL,

Krueger GG, et al. Topical metronidazole maintains remission of rosacea.

Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:679-683.

16. Wilkin J. Use of

topical products for maintaining remission in rosacea. Arch Dermatol.

1999;135:79-80.

17. Mackley CL,

Thiboutot DM. Diagnosing and managing the patient with rosacea. Cutis.

2005;75:25-29.

18. Saunder D, Miller

R, Gratton D, et al. The treatment of rosacea: safety and efficacy of sodium

sulfacetamide 10% and sulfur 5% lotion is demonstrated in a double blind

study. J Dermatol Treat. 1997;8:79-85.

19. Del Rosso J. A

status report on the medical management of rosacea: focus on topical

therapies. Cutis. 2002;70:271-275.

20. Lacy C, Armstrong

L, Goldman M, et al. Drug Information Handbook. 10th ed. Hudson, OH:

Lexi-Comp; 2002-2003:1268-1269.

21. Thiboutot D,

Theiroff R, Graupe K. Efficacy and safety of azelaic acid (15%) gel as new

treatment for papulopustular rosacea: results from two randomized phase III

studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:836-845.

22. Elewski B,

Fleischer A, Pariser D. A comparison of 15% azelaic acid gel and 0.75%

metronidazole gel in the topical treatment of papulopustular rosacea. Arch

Dermatol. 2003;139:1444-1450.

23. Mills H, Kligman M.

Topically applied erythromycin in rosacea. Arch Dermatol.

1976;112:553-554.

24. Blount W, Pelletier

A. Rosacea: a common, yet commonly overlooked, condition. Am Family

Physician. 2002;66:435-442.

25. Wilkin J, Dewitt S.

Treatment of rosacea: topical clindamycin versus oral tetracycline. Int J

Dermatol. 1993;32:65-67.

26. Bladwin H. Oral

therapy for rosacea. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:16-21.

27. Bikowski J.

Subantimicrobial dose doxycycline for acne and rosacea. SKINmed.

2003;2:234-245.

28. Oracea

[package insert]. Newton, PA: CollaGenex Pharmaceuticals Inc.; May 2006.

29. Rosso D. Results of

phase 3 clinical trials of Oracea. Dermatology Times. 2005;26(9):34.

Abstract.

30. Lacy C, Armstrong

L, Goldman M, et al. Drug Information Handbook. 10th ed.

Hudson, OH: Lexi-Comp; 2002-2003:1306-1308.

31. Torresani C, Pavesi

A, Manara G. Clarithromycin versus doxycycline in the treatment of rosacea.

Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:942-946.

32. Bakar O, Demircay

Z, Gurbuz O. Therapeutic potential of azithromycin in rosacea. Int J

Dermatol. 2004;43:151.

33. Erdogan F,

Yurtsever P, Aksoy D, et al. Efficacy of low dose isotretinoin in patients

with treatment-resistant rosacea. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:884-885.

34. Accutane [package

insert]. Nutley, NJ: Roche Inc.; August 2005.

35. Lonne-Rahm S,

Nordlind K, Wiegleb D, et al. Laser Treatment of Rosacea. Arch Dermatol

. 2004;140:1345-1349.

36. Sadick N. A

structural approach to nonablative rejuvenation. Cosmetic Dermatol.

2002;15:39-43.

To comment on this article, contact uspharmacist.com.