US Pharm. 2006;7:10-13.

Characterized by severe elevation in

the mean pulmonary arterial pressure and pulmonary vascular resistance,

pulmonary hypertension is a devastating chronic disease with a poor long-term

prognosis. The early symptoms (e.g., difficulty in breathing, fatigue) and

later manifestations (e.g., palpitations, fainting) are shared with other

diseases. Hence, treatment may be delayed while physicians exclude other

causes for these symptoms. Results from a national registry of patients with

primary pulmonary hypertension indicated that the duration from onset of

symptoms to death averaged 2.8 years.

In recent years, new

treatments have become available for pulmonary hypertension, particularly for

pulmonary arterial hypertension. The treatments, which include anticoagulants,

calcium channel blockers, and prostacyclins, prolong survival and provide

clinical improvement, but they can be expensive. Although effective management

might be possible with early detection, most people are diagnosed with

pulmonary hypertension in later stages of the disease, making treatment more

difficult and less successful. Pulmonary hypertension is reported on hospital

records and death certificates either as primary pulmonary hypertension or as

pulmonary hypertension secondary to another underlying condition or disease.

Pulmonary hypertension might be secondary to congenital heart disease,

valvular heart disease, chronic thromboembolic disease, lung diseases, liver

diseases, sleep-disordered breathing, hypoxemia, lupus, scleroderma,

rheumatoid arthritis, vasculitis, or HIV infection. Limited national

statistics are available regarding pulmonary hypertensive diseases. Although a

rare condition, primary pulmonary hypertension as the reported cause of death

has increased since 1979, and the number of all cases is likely to be higher

than reported numbers because of difficulties in diagnosis.

Hospitalizations

During 1980 to

2002, the estimated number of hospitalized patients with pulmonary

hypertension as the diagnosis tripled for the total U.S. population. Compared

with estimated numbers of hospitalizations in 1980, the numbers in 2002 were

two times higher among men and three times higher among women. Rates of

hospitalization for pulmonary hypertension among women were higher than those

in men, but only after 1995. In 2002, the hospitalization rate (per 100,000

population) for pulmonary hypertension as the diagnosis was 95.3 for women and

82.3 for men. The number of hospitalizations and hospitalization rates

increased among all age-groups in the U.S. population. The greatest increase

in hospitalization rates was among adults 75 years and older.

During 1980 to 2002, the

greatest increase in hospitalizations for pulmonary hypertension occurred in

men 85 years and older and in women 65 years and older. Because of major

increases in hospitalizations among women 85 years and older during 2000 to

2002, women had higher hospitalization rates than men did in this older

age-group.

During 1980 to 2002, trends in

the most commonly reported principal diagnoses changed. From 1980 to 1984, the

most commonly reported principal diagnoses among hospitalized patients with a

diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension were chronic lower respiratory diseases

(42%), followed by pulmonary hypertension (12.8%) and cardiovascular diseases

(6.8%). By 2000 to 2002, heart failure (18.7%) was the most commonly reported

principal diagnosis among hospitalized patients with a diagnosis of pulmonary

hypertension; this was followed by chronic lower respiratory diseases (12.9%).

During 2000 to 2002, pulmonary hypertension was the principal diagnosis in

only 4.2% of hospitalizations involving a diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension.

Declines in reporting pulmonary hypertension and chronic lower respiratory

disease and the increase in reporting heart failure as the principal diagnosis

in these cases were observed among all groups defined by sex and age.

Among those younger than 45

years who were hospitalized, the principal diagnosis was more likely to be

pulmonary hypertension (26%) and congenital malformations (22.9%) during 1980

to 1984; however, by 2000 to 2002, these conditions had declined as the

principal diagnoses among hospitalized patients with pulmonary hypertension as

the listed diagnosis. Other cardiovascular diseases (29.8%), other respiratory

diseases (9.8%), pulmonary hypertension (9.5%), and chronic lower respiratory

diseases (7.1%) were the major principal diagnoses from 2000 to 2002. Among

patients younger than 45 years who were hospitalized for pulmonary

hypertension, influenza and pneumonia (4.6%), congenital malformations (4.3%),

complications related to specific procedures (3.9%), cellulitis and abscesses

(3.6%), and complications related to pregnancy and childbirth (3.2%) were

principal diagnoses.

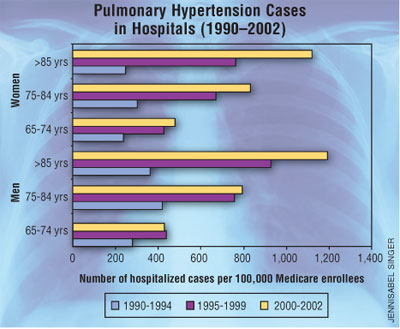

Medicare Claims

During 1990 to

2002, the annual number of hospitalizations among Medicare enrollees 65 years

and older who had pulmonary hypertension as a diagnosis tripled from 55,516 to

187,205. Until 1999, men were more likely than women to be hospitalized for

pulmonary hypertension. Increases in numbers of Medicare hospitalizations for

pulmonary hypertension were observed among all groups defined by race and age.

Hospitalization rates were higher for blacks than for whites. Hospitalization

rates increased for all age-groups, but the rates were not the highest among

adults ages 85 years and older until after 1995. By 2000 to 2002,

hospitalization rates were higher among women ages 65 to 74 years and 75 to 84

years, and whites ages 85 years and older had higher hospitalization rates

than did blacks in the same age-group.

Conclusion

The high proportion

of pulmonary hypertension-related deaths and hospitalizations that occurred

among adults 65 years and older suggests that as the proportion of older

adults in the U.S. population increases, pulmonary hypertension might continue

to be a more frequent diagnosis, particularly with concomitant chronic heart

failure. Because the majority of patients with pulmonary hypertension are

older adults, the burden of chronic disability and morbidity on the Medicare

system and families will increase.

Prevention efforts, including

broad-based public health efforts to increase awareness of pulmonary

hypertension and foster appropriate diagnostic evaluation and timely

treatment, should be considered. Although multiple predisposing factors and

associated conditions have been identified for pulmonary hypertension, the CDC

believes that the causal roles and strengths of association have not been well

established. Thus, it is not possible to establish preventive measures

regarding risk factor reduction.

To comment on this article, contact

editor@uspharmacist.com.