US

Pharm. 2006;5:HS-21-HS-33.

The impact of licit (i.e.,

alcohol and nicotine used legally), illicit, and nonmedical prescription drug

abuse and dependence in the United States is a well-documented matter

affecting many individuals in the general population. A substantial number of

patients served daily by pharmacists in community, hospital, and other health

care facilities are therefore abusing or are dependent on alcohol, other

drugs, or a combination (AOD). Despite this, a recent report concerning

substantial abuse of prescription medication in the U.S. reported that many

pharmacists are poorly trained to deal with alcohol or drug abuse.1

As one of America's most

trusted professionals, the public expects pharmacists to respect the proper

use of the medicines that they dispense to their patients.2 Just as

in their patients, though, alcohol and other drug abuse and dependence are

affecting the lives of a number of pharmacists, leading some researchers to

call pharmacists our society's "drugged experts."3 In

reality, while pharmacy students and pharmacists report somewhat higher

lifetime and past-year prevalence of prescription drug use of opioids and

anxiolytics than comparable groups of college students or the general

population, respectively, lifetime and past-year prevalence of illicit drug

use overall is less likely to be reported by pharmacy students and pharmacists.

4,5

Although not a widely

discussed or well-researched topic, the issue of pharmacists impaired by

prescription, illegal, and legal drug abuse needs to be addressed. Beginning

in pharmacy college, some students may develop an air of invulnerability and

immunity to addiction, perhaps because of an advanced understanding of drug

action. What begins as recreational college AOD use may, for some individuals,

develop into a complicated pattern of AOD abuse or dependence intended to

produce a "sense of well-being" without an overt manifestation of intoxication

or side effects.6,7 This concept of balancing drug effects, also

called titration, refers to a practice in which pharmacists use their

pharmacological knowledge to balance drug actions and reactions by "enhancing,

neutralizing, or counteracting specific drug effects through ingesting

multiple types of drugs."8

When a pharmacist

experiences drug impairment, the responsibility to protect the public

ultimately falls upon the pharmacy profession, as represented by the licensing

boards and professional societies. The pharmacy practice act of each state

describes the parameters of professional activity. When a pharmacist violates

these laws, he or she is subject to punitive board action, such as license

suspension or revocation. In addition to board prosecution, state pharmacy

professional organizations can organize, sponsor, or support a pharmacist

recovery network (PRN) program. These programs offer confidential support and

assistance to pharmacists who are impaired by drug or alcohol abuse or

dependence, and/or emotional or mental health problems.9

Whether through board action

or collegial PRN intervention, the impaired pharmacist is taken out of

practice until the impairment is resolved. Furthermore, since AOD abuse and

dependence exists in nondistinct shades of gray, pharmacists (and other health

care professionals) are often ill-prepared to deal effectively with AOD abuse

and dependence by patients, others in the profession, or themselves.10

Scope of the Problem

The National

Survey on Drug Use and Health in 2004 reported that 22.5 million Americans

ages 12 years and older abused or were dependent on AOD during the year before

the survey.11 This rate of abuse or dependence equals 9.4% of the

U.S. population. Additionally, more than six million individuals reported

using nonprescribed psychotherapeutic agents.

While pharmacists may be at

greater risk of using prescription drugs than the general population, there is

currently no evidence that total lifetime or past-year drug use by pharmacists

significantly exceeds that of other major groups of health care professionals

or the general population. 12 However, it appears that the greatest

threats to pharmacists are nonmedical opiate, stimulant, and antianxiety drug

use (due to easy availability), as well as legal drugs, alcohol, and nicotine.

12 Most nonprescribed opioid and antianxiety drug use by pharmacists is

taken for self-diagnosed ailments, while most stimulant use is taken to

facilitate performance.13 Consistent with previous research, a

study found that the majority of pharmacists who used these drugs initially

did so after leaving college.14 In addition, 40% of pharmacists

reported that they had used a prescription drug without a physician's

authorization, and 20% reported that they had done so five or more times in

their lifetime.14

What Are Chemical Abuse,

Dependence, and Addiction?

The terms abuse

, dependence, and addiction appear to be confusing to the

public and health care professionals since there is both a colloquial (which

is how we will be using these terms) and a diagnostic use of the terms for

alcohol or any other substance overuse. The term substance abuse is

commonly used as a substitute for any use of an illegal substance. However,

since there is no substance that is not a chemical or drug, the term

substance is problematic. In contrast, treatment professionals limit the

use of the term substance abuse to describe the symptoms of individuals

who meet the specific criteria for a medical diagnosis of abuse as listed in

the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, as discussed

below. 15 Substance (i.e., drug, chemical) abuse is a pattern of

AOD overuse that produces many adverse results during continual use of the

chemical. The diagnostic characteristics of chemical abuse include at least

one of the following behaviors determined to be present in a 12-month period

by a qualified assessment professional:

•Failure to carry out

obligations at home or work.

•Recurrent social or

interpersonal problems.

•Continual use of the

drug in circumstances that present a hazard (e.g., driving a car), and legal

problems, such as arrests.

•Use of the drug is

persistent, despite personal problems caused by the effects of the chemical on

oneself or others.

The term AOD dependence

, on the other hand, has been medically defined as a group of behavioral

and physiological symptoms that indicate the continual, compulsive use of

chemicals in self-administered doses, despite the problems related to the use

of the drug.15 The diagnostic characteristics of dependence,

popularly called addiction, include the presence of at least three of

the following behaviors in a 12-month period, as determined by a qualified

assessment professional:

•Tolerance.

•Signs of withdrawal

(vary by drug class).

•Use of larger

amounts of the drug or for a longer period of time than intended.

•Persistent desire or

unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control use.

•Continual use

despite adverse consequences.

•An excessive amount

of time and effort spent obtaining the drug.

•Social,

occupational, or recreational activities given up or time spent doing them

reduced.

Tolerance is evident when

the same amount of drug results in a diminished effect or increased amounts of

the drug are needed to achieve the desired result or level of intoxication.

Withdrawal signs and symptoms signify physiological and psychological changes

that occur when the body's concentration of the chemical declines in a person

who has been a heavy user. Given the neurophysiological changes occurring with

chronic AOD abuse, withdrawal symptoms are typically actions opposite to those

of the drug. For example, alcohol's sedative effect results in increased

autonomic hyperactivity when alcohol is withdrawn. When signs of tolerance or

withdrawal are seen, the AOD abuser is said to be "physiologically dependent."

Pharmacy's Role in Drug

Abuse Prevention and Education

Generally,

pharmacists receive inadequate education on drug abuse.16 More

specifically, pharmacy students and pharmacists are insufficiently trained to

identify, intervene, or treat patients and coworkers with drug abuse problems.

17,18 In a study published by the Center on Addiction and Substance

Abuse (CASA) in 2005, only 48% of the 1,030 registered pharmacists surveyed

had received any training in preventing drug diversion.1 Moreover,

only 49% had received training in identifying abuse or dependence since

graduation from pharmacy college. The perception by practicing pharmacists is

that proficiency in drug abuse prevention, education, and even treatment

options must be addressed in pharmacy college.16 The CASA study

also revealed that only about half of the pharmacists surveyed rated the

substance abuse education and training they received in college as good or

excellent.

In addition to drug abuse

education and training before and after graduation from pharmacy college,

opportunities for specialization in residency programs should be provided, and

pharmacist involvement in community service and drug abuse treatment research

should be encouraged.19 In 2003, the American Society of

Health-System Pharmacists published a position statement, noting that

pharmacists have a distinct opportunity to have a fundamental role in drug

abuse prevention, education, and assistance.20 Given the extent and

consequences of potential chemical abuse in the workplace, pharmacy must

accept a responsibility for educating its own profession. As health care

professionals with an abundance of drug knowledge and responsibility,

pharmacists should shoulder the responsibility of leading drug abuse

prevention and education efforts. Pharmacists are also needed to assist in

patient care, employee health, and community activities. The most important

activity the profession can facilitate is promoting the understanding of drug

abuse and dependence among pharmacy students and pharmacists.

Educating Pharmacists and

Pharmacy Students About Drug Abuse and Dependence

Pharmacy colleges

in several states have begun to more proactively educate the profession in

this long-neglected area. While guidelines have been published for including

this topic in pharmacy education, the suggestions have been mostly ignored.

21 Several exceptions are the 20 hours of core content on drug abuse and

dependence offered at the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy and the

eight hours of core content in the main pharmacotherapy course at the

University of Texas College of Pharmacy, which also offers a five-hour

orientation program on the disease of chemical dependence, intervention, and

resources for students entering the college. In addition, the University of

Nebraska College of Pharmacy includes six hours of core content in its

pharmacotherapy course and offers a substance abuse elective that

approximately 80% of its students complete. The university provides a brochure

to all students and faculty annually that details its chemical dependency

assistance program and local resources, and it provides a program overview

during new student orientation.

In 2000, the Texas State

Board of Pharmacy approved four policies for implementation: (1) to support

the concept of more training in chemical dependency for Texas pharmacists; (2)

to support the attitude that such training is needed to protect the public;

(3) to encourage Texas colleges of pharmacy to offer required lectures on

chemical dependency; and (4) to move toward setting minimum standards for

certification of pharmacists trained in chemical dependency. While the final

policy has not yet been implemented, the University of Texas School of

Pharmacy has produced 12 hours of chemical dependency training ("Because They

Trust Us" continuing education videotapes) and a micro-Web C.E. learning

series, "Neurobiology of Addiction."22

The Basics: What

Pharmacists Need to Know About AOD Abuse and Dependence

All health care

professionals are being called to action in the effort to address the problems

of drug abuse and dependence in the U.S.23 At a minimum,

pharmacists should be able to screen for these problems, assess their

severity, refer individuals to appropriate levels of care, and provide

appropriate counseling for those in recovery. To perform these activities,

pharmacists should be educated about them and possess an ethic that promotes

the necessary deployment of skills. For instance, pharmacists need logistical

support in their practice environment to provide these services. This entails

sufficient time to engage patients in counseling and an area that affords

privacy and confidentiality. Pharmacy owners and managers, as well as

dispensing pharmacists, need to make workplace accommodations that demonstrate

the commitment to this professional activity.

Screening patients for

substance abuse disorders is essential. Consider the number of prescriptions

dispensed with an auxiliary label that warns patients against the use of

alcohol "while taking this medication." For individuals who are dependent on

alcohol, such advice would be difficult to follow. The pharmacist who advises,

"If you find that you are unable to refrain from alcohol use during the period

of prescription therapy, I strongly recommend that you seek assistance," may

spark a turning point in the life of an individual who otherwise feels in

total control of alcohol.

Pharmacists also practice in

varied settings. For those in clinics, it may be practical to follow up a

positive drug screening with assessment questions that estimate the dose,

frequency, and duration of AOD overuse. A patient's responses to these

questions will reveal information that will affect the treatment of other

conditions (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, anticoagulation therapy) and perhaps

suggest the need for treatment of an AOD abuse or dependence disorder.

Clinical pharmacists can easily become frustrated when the dependent patient

displays nonadherence to medication regimens and disease management advice.

Until the chemical dependence is diagnosed and treated, the adverse effects of

a patient's substance abuse on medication adherence and treatment outcomes for

other illnesses are likely to continue.

In community pharmacy

practice, assessment is less practical. Unless the pharmacist has made a

concerted effort to spend time with patients in confidential counseling, the

exigencies of dispensing leave little time for assessment. The advent of

medication therapy management may provide sufficient incentive for community

pharmacists to make the necessary arrangements to routinely engage in more

therapeutic conversations with patients regarding their pharmacotherapy.

24

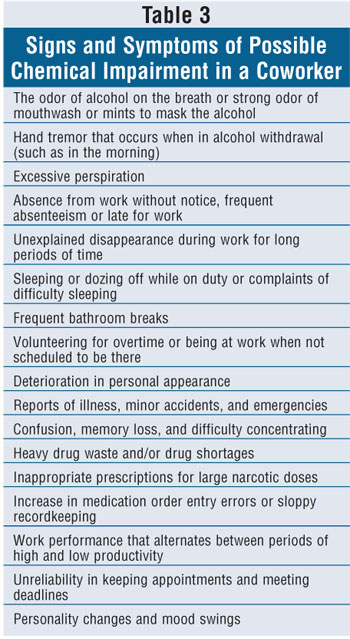

Pharmacy practice

necessitates educating students and pharmacists on the identification of

abusing and dependent patients, referral to evaluation and support resources

for individuals affected by AOD use or those concerned about them, common

prescription scams such as patient claims of "lost" or "stolen" narcotic

analgesics and prescription forgeries, and serving as a resource for

assistance-related materials and other information (patient resources).

Updating the paradigm of pharmacy as the gatekeeper to include pharmacy as the

educator includes enhancing the role of the pharmacist in supporting addiction

recovery. For example, pharmacists can counsel on the use of addicting and

mood-altering medications, provide appropriate counseling about what is not

addiction, and counter "addiction phobias" for those patients (e.g., hospice

patients) who require significant pain control but fear becoming addicted to

the prescribed medication.

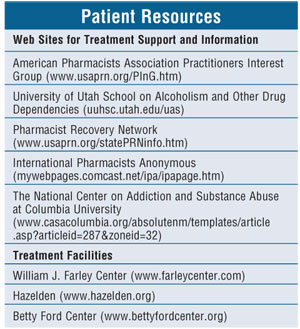

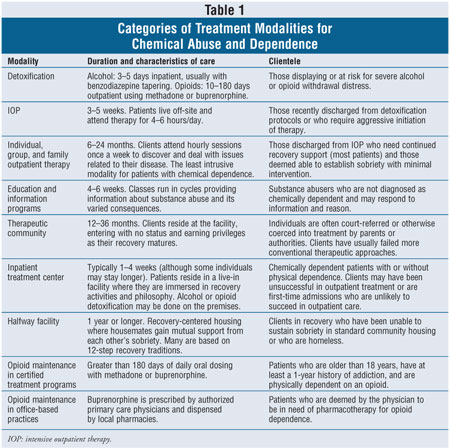

A multitude of resources exists to treat AOD abuse and dependence disorders. The major treatment options available in the community are listed in table 1, and the currently available medications for alcohol and opiate dependence treatment are listed in table 2. The thorough assessment is a critical prerequisite to a proper referral. Little is gained when needs and services are mismatched. Much time and money are wasted by individuals who minimize the severity of their AOD abuse or dependence and participate in an inadequate level of care.

Taking Care of Our Own:

Pharmacy Profession Response to Chemical Abuse and Dependence in Pharmacists

The goals of

ethical standards and licensing laws in the health professions include

protecting the public and establishing the boundaries of professional conduct.

Stepping outside the standards of conduct and violating practice regulations

expose errant practitioners to sanction. However, nonpunitive options increase

the likelihood that pharmacists will refer themselves for intervention and

that other pharmacists will refer an impaired colleague. Employee assistance

programs (EAPs) utilize a rehabilitative approach to chemical abuse and

dependence in the workplace. For over 50 years, these programs have offered

assistance to workers with various problems, such as AOD overuse, that

negatively affect their job performance.25 This approach offers

confidential assistance to employees who request help. Workers who enter an

EAP are afforded an opportunity to deal with a substance use disorder in a

therapeutic setting while the worker's supervisor relies solely on job

performance criteria for making decisions about continued employment.

The PRN providers use the

rehabilitative approach to assist pharmacists who abuse or are dependent on a

drug. PRN programs limit their outreach and intervention services to

pharmacists, pharmacy students, and pharmacy technicians. Umbrella programs

offer assistance to multiple professions for various problems, including

psychoactive substance dependence assistance, through a central provider. Both

programs are modeled after EAPs and identify individuals for rehabilitative

intervention, rather than punitive action.

PRN services, available in

all 50 states, offer an alternative to board of pharmacy license sanctions

when dealing with a pharmacist who has AOD problems.26 Pharmacists

who need and want confidential help can contact their state PRN. Organized in

1982 by the American Pharmacists Association (APhA, formerly the American

Pharmaceutical Association), the program is dedicated to the early

identification, intervention, and treatment of drug-affected pharmacists,

pharmacy students, and technicians. Pharmacists who have an AOD problem can

call their state PRN to ask for confidential advice and assistance.

Information is collected and the individual is referred for follow-up to a

counselor or a chemical dependency assessment and treatment specialist. Early

discovery of such individuals preserves both professional health and public

safety.

Identifying Drug Problems

in Coworkers

Most corporate

chain store retailers and hospital pharmacies use statistical analysis to

determine worker access to specific drugs on a periodic basis (e.g., monthly).

If a particular employee appears to consistently access controlled drugs more

often than his or her peers without sufficient cause, a more formal

investigation is begun, perhaps instituting the use of video cameras or

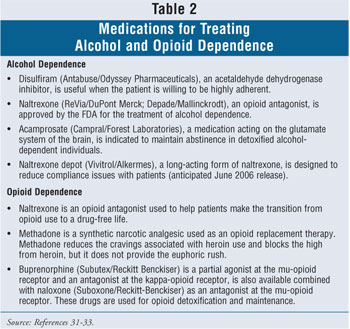

auditing the site. Behaviorally, however, there are several signs and symptoms

of AOD abuse that coworkers may notice (table 3). In fact, some of these

markers may indicate the type of impairment. For example, unexplained work

absences may indicate an alcohol abuse or dependence problem, since home is

the more convenient place to store and access alcohol. In contrast,

consistently volunteering to work overtime or work with controlled substance

inventory, and arriving at work at unscheduled times, provides an impaired

coworker the opportunity to access controlled substances that are not

available at home. Unfortunately, such symptoms are more easily identified in

hindsight than before a coworker is identified to have an AOD disorder.

Probably one of the most difficult

professional decisions a pharmacist can make is to confront a coworker with an

AOD problem. Given the seriousness of dependence disease and its treatment,

intervention can be awkward. More importantly, pharmacists should consider

that in retrospect, many colleagues feel that an intervention probably saved

their life.8 Also, while these individuals may have been devastated

at the time of their discovery, the reality is that the majority do

successfully return to work, which will be detailed shortly. Furthermore,

given the shortage of pharmacists, it is probable that many of these

individuals will be allowed to resume their profession if they cooperate with

treatment, which may include compensation to the employer for the diverted

drugs in cases of criminal diversion.20

Recovery Assistance

Programs, Risk Factors for Relapse, and Treatment Success

Once an

individual's AOD problem surfaces, treatment decisions are generally tailored

to his or her needs (tables 1, 2). While discussing the diverse treatment

options available in a meaningful way is beyond the scope of this article,

certain basic goals of treatment include matching the patient to the correct

level of care, such as deciding whether an individual is better suited for

inpatient versus outpatient treatment.27 Beyond placement, the

fundamental facets of treatment include individual and group therapy,

pharmacotherapy when appropriate, urine drug screens, and 12-step

facilitation. Twelve-step programs include Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics

Anonymous, Caduceus (for health care professionals), International Pharmacists

Anonymous (a psychosocial support group specifically for pharmacists), and

International Doctors in Alcoholics Anonymous (a support group that now

includes pharmacists in its membership, regardless of pharmacy degree).

There is inadequate research

assessing risk factors for relapse or treatment success of recovering

pharmacists. In a retrospective cohort study of 292 health care professionals,

including pharmacists enrolled in Washington state's Physicians Health

Program, only about 25% of the study population had one or more relapses.

28 The risk of relapse was significantly higher in health care

professionals who used a major opioid, had a coexisting psychiatric illness,

or reported a family history of an AOD disorder. Coexisting risk factors and

previous relapse also increased the likelihood of relapse.

In 1988, a survey examined

pharmacist assistance programs in all 50 states and the District of Columbia.

29 The survey reported that only 20% of impaired pharmacists in these

treatment programs voluntarily disclosed their chemical use problem. Most

importantly, just over 88% successfully completed treatment and returned to

practice. These studies suggest that the goal of returning a recovering

pharmacist to practice with the proper aftercare and monitoring program is

realistic and almost always successful.

Since 1982, APhA has worked

to adopt and institute a policy of treatment, prevention, and rehabilitation

of pharmacists who use AOD. For over 20 years, APhA has actively supported the

pharmacy section of the Utah School on Alcoholism and Other Drug Dependencies

in Salt Lake City. The purpose of this annual weeklong program is to bring

together pharmacists and pharmacy students with various state PRN

coordinators, state administrators, industry representatives, and interested

individuals from around the country to listen to updates on various aspects of

AOD intervention and treatment.

The Health Professional

Students for Substance Abuse Training (HPSSAT) is a project of the Physician

Leadership on National Drug Policy that is free to join.30 The goal

of this organization is to have all graduating health professional students

develop the skills to screen, diagnose, and provide appropriate intervention

for patients with an AOD problem. Through HPSSAT, students can be advocates

for local and national educational reform of substance abuse education and

treatment training.

Conclusion

Agencies such as the

Drug Enforcement Administration, state departments of health, boards of

pharmacy, state pharmacy associations, and colleges of pharmacy should

coordinate discussions about AOD use among patients, as well as pharmacists

and pharmacy students. Dissemination of information (e.g., continuing

education opportunities) relating to the warning signs of drug abuse and

sources of help for those affected by AOD should be continual goals of these

agencies. Colleges of pharmacy should pay particular attention to providing

instruction on the neurobiological and psychological processes of AOD

dependence and, in particular, the threats posed by alcohol, nicotine,

opioids, stimulants, and antianxiety drugs, since these are the drugs most

associated with abuse, dependence, and health problems. Efforts to dissuade

pharmacists and pharmacy students from using AOD may not immediately produce

visible results. Ultimately, however, academic and governmental agencies need

to make every reasonable effort to educate both future and practicing

pharmacists about these issues.

While the rates of AOD abuse

or dependence among pharmacists are no greater than in the general population,

the consequences of any impairment can have adverse effects on patients.

People entrust their personal welfare and safety to those in the health

professions. The profession, in turn, has an ethical obligation to ensure that

its practitioners can discharge their duties with skill and safety. Policies

should promote early discovery of professionals who overuse AOD in order to

minimize the period of time that patients are at risk of being harmed.

Dedicated to the memory of

Lance Smith, BS, pharmacy class of 2001, University of Rhode Island, Kingston.

REFERENCES

1. The National

Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University. Under the

Counter: The Diversion and Abuse of Controlled Prescription Drugs in the U.S.

New York, NY; 2005.

2. Gallup

Organization. Honesty/Ethics in Professions. Available at:

www.gallup.com/poll/content/login.aspx?ci=14290. Accessed August 26, 2005.

3. Dabney D,

Hollinger R. Illicit prescription drug use among pharmacists: evidence of a

paradox of familiarity. Work Occupations. 1999;26:102.

4. Office of Applied

Studies. Results from the 2002 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary

of national findings. Rockville, Md.; Substance Abuse and Mental Health

Services Administration; 2003. NHDUH series H-22; U.S. Department of Health

and Human Services publication SMA 03-3836.

5. Kenna GA, Wood MD.

Substance use by pharmacy and nursing practitioners and students in a

northeastern state. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61:921-930.

6. McAuliffe WE,

Santangelo SL, Gingras J, et al. Use and abuse of controlled substances by

pharmacists and pharmacy students. Am J Hosp Pharm . 1987;44:311-317.

7. McGuffey EC.

Lessons from pharmacists in recovery from drug addiction. J Am Pharm Assoc

. 1998;38:17.

8. Dabney D. A

sociological examination of illicit prescription drug use among pharmacists

[unpublished dissertation]. Gainesville, Fla: University of Florida; 1997:97.

9. Tommasello AC.

Substance abuse and pharmacy practice: what the community pharmacist needs to

know about drug abuse and dependence. Harm Reduct J. 2004;1:3. Available at:

www.harmreductionjournal.com/content/pdf/1477-7517-1-3.pdf. Accessed August

25, 2005.

10. Lawson KA, Wilcox

RE, Littlefield JH, et al. Educating treatment professionals about addiction

science research: demographics of knowledge and belief changes. Subst Use

Misuse. 2004;39:1235-1258.

11. Office of Applied

Studies. Results from the 2004 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary

of national findings. Rockville, Md.; Substance Abuse and Mental Health

Services Administration; 2005. NHSDA series H-282; U.S. Department of Health

and Human Services publication SMA 03-3836.

12. Kenna GA, Wood

MD. Prevalence of substance use by pharmacists and other health professionals.

J Am Pharm Assoc. 2004;44:684-693.

13. McAuliffe WE,

Rohman M, Santangelo S, et al. Psychoactive drug use among practicing

physicians and medical students. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:805-810.

14. Dabney D. Onset

of illegal use of mind-altering or potentially addictive prescription drugs

among pharmacists. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2001;41:392-400.

15. Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-IV-TR (Text Revision).

Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

16. Graham A, Pfeifer

J, Trumble J, Nelson ED. A pilot project: continuing education for pharmacists

on substance abuse prevention. Subst Abus . 1999;20:33-43.

17. Baldwin JN, Light

K, Stock C, et al. Curricular guidelines for pharmacy education: substance

abuse and addictive disease. Am J Pharm Educ. 1991;55:311-316.

18. Dole EJ,

Tommasello A. Recommendations for implementing effective substance abuse

education in pharmacy practice. In: Haack MR, Adger H, eds. Strategic Plan

for Interdisciplinary Faculty Development: Arming the Nation's Health

Professional Workforce for a New Approach to Substance Use Disorders.

Providence, R.I.: Association for Medical Education and Research in Substance

Abuse (AMERSA); 2002:263-271.

19. Cobaugh DJ.

Pharmacist's role in preventing and treating substance abuse. Am J Health

Syst Pharm. 2003;60:1947.

20. ASHP statement on

the pharmacist's role in substance abuse prevention, education and assistance.

Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2003;60:1995-1998.

21. Baldwin JN, Dole

EJ, Levine PJ, et al. Survey of pharmacy substance abuse course content. Am

J Pharmaceut Educ. 1994;58(suppl):47S-52S.

22. University of

Texas College of Pharmacy. "Because They Trust Us" continuing education

videotapes and micro-web C.E. learning series on the "Neurobiology of

Addiction." Available at: www.utexas.edu/pharmacy/ce/BTTU.html. Accessed

February 9, 2006.

23. Haack MR, Adger

H. Strategic plan for interdisciplinary faculty development: arming the

nation's health professional workforce for a new approach to substance use

disorders. Substance Abuse. 2002;23:1-21.

24. American

Pharmacists Association. Understanding Medicare Reform: What Pharmacists

Need to Know (monograph 2): Medication Therapy Management Services and Chronic

Care Improvement Programs. Washington, DC: APhA; 2004.

25. Steele PD, Trice

HM. A history of job-based alcoholism programs: 1972-1980. J Drug Issues

. 1995;25:397-422.

26. Pharmacist

Recovery Network. Available at: www.usaprn.org. Accessed January 15, 2006.

27. Nace EP.

Achievement and Addiction: A Guide to the Treatment of Professionals. New

York, NY: Brunner/Mazel; 1995.

28. Domino KB,

Hornbein TF, Polissar NL, et al. Risk factors for relapse in health care

professionals with substance use disorders. JAMA. 2005;293:1453-1460.

29. McNees GE, Godwin

HN. Programs for pharmacists impaired by substance abuse: a report. Am Pharm

. 1990;NS30:33-37.

30. Health

Professional Students for Substance Abuse Training. Available at:

www.hpssat.org/about/index.html. Accessed February 9, 2006.

31. Kenna GA, McGeary

JE, Swift RM. Pharmacotherapy, pharmacogenomics and the future of alcohol

dependence therapy. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61(21)part

1:2272-2279.

32. Kenna GA, McGeary

JE, Swift RM. Pharmacotherapy, pharmacogenomics and the future of alcohol

dependence therapy. Am J Health Syst Pharm . 2004;61(22)part

2:2380-2390.

33. Gerada C. Drug

misuse: a review of treatments. Clin Med. 2005;5:69-7 3.

To comment on this article, contact editor@uspharmacist.com .