US Pharm.

2006;7:28-34.

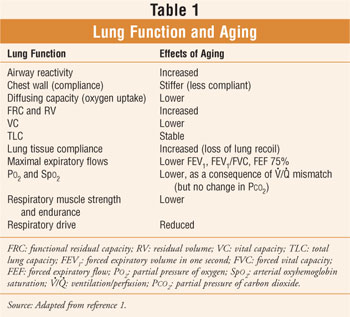

Age impacts lung function. It is an

undisputed fact that changes in lung function occur with aging in healthy,

nonsmoking individuals (Table 1).1 If an individual smokes,

the situation is compounded and havoc can strike. Chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease (COPD) is the most common chronic respiratory disease among

seniors. In addition, COPD morbidity and mortality are on the rise.1,2

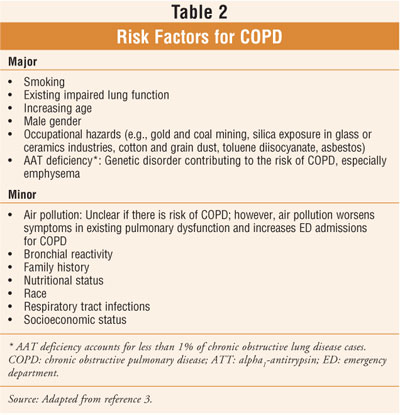

Although there are numerous risk factors

associated with COPD (Table 2), the disease is largely preventable,

since its main cause is cigarette smoking. In lifetime nonsmokers in whom

exposure to environmental tobacco smoke results in at least some disease, COPD

is rare (estimated incidence 5% in three large representative U.S. surveys

from 1971 to 1984).3-5 In fact, smoking accounts for approximately

85% of COPD mortality in men and 69% of COPD mortality in women.6

A national report published in

2000 notes that 14% of all hospital admissions of elderly individuals are due

to respiratory disease.7 According to 1995 mortality statistics,

COPD and associated conditions accounted for 5% of all deaths in people 65

years and older.8 In the U.S., estimated prevalence of COPD has

risen by 41% since 1982.9 In 2003, 10.7 million adults in the U.S.

were estimated to have COPD.10 It should be noted that the terms

chronic obstructive lung disease and chronic obstructive airway disease

are synonymous with COPD.

Characterized by a progressive airflow

limitation, COPD is caused by an abnormal inflammatory reaction to the chronic

inhalation of particles, of which those from cigarette smoke are most

prevalent.3,11 For patients who continue to smoke, airway

obstruction is usually progressive, resulting in early disability and

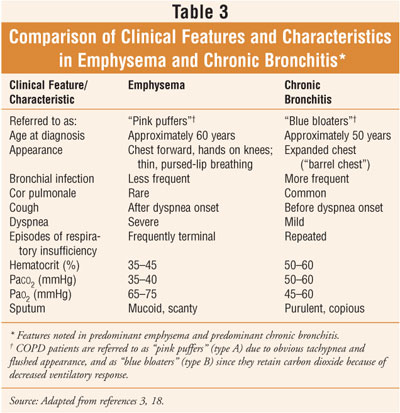

shortened survival.9 The subsets of COPD are chronic bronchitis and

emphysema; while their pathology and clinical characteristics differ (Table

3), most individuals with COPD show characteristics of both.3

Pathophysiology and

Presentation

Chronic

bronchitis is defined in

clinical terms as chronic cough or mucus production for at least three months

in at least two successive years when other causes of chronic cough have been

excluded.3,6 Emphysema is defined in terms of anatomic pathology

and is described as an abnormal permanent enlargement of the air spaces distal

to the terminal bronchioles, accompanied by destruction of their walls

(without obvious fibrosis).1 The destruction takes place within the

acinus, the unit of the lung responsible for gas exchange. Patients with

emphysema have a decreased number of capillaries in the walls of the alveoli.

Fewer blood vessels and airway obstruction causes impaired movement of oxygen

and carbon dioxide between the alveoli and the blood.12

Patients who present with predominant

emphysema tend to be older than those who present with predominant chronic

bronchitis (Table 3). Patients with COPD may have symptoms associated

with a severely low blood oxygen level, including shortness of breath,

pulmonary hypertension, right-sided heart failure, and polycythemia (an

increase in the total red blood cell mass of the blood).12 If the

hematocrit is more than 55% to 60%, acute phlebotomy may be indicated.3

To maintain a lower hematocrit, long-term oxygen may be necessary.3

Diagnosis and Prognosis

The diagnosis of

emphysema is based on medical history, physical exam, and pulmonary function

tests. Chronic bronchitis is diagnosed solely by a history of a persistent,

sputum-producing cough.12 Due to the high prevalence of

comorbidity, the differential diagnosis of COPD and asthma in the elderly is

frequently more difficult than in younger patients.1 As compared to

middle-aged adults, elderly patients are more likely to have COPD and

cardiovascular disease, both of which are often associated with cigarette

smoking and have symptomatology mimicking asthma.1 Objective

pulmonary function (PF) tests, therefore, have great value in the elderly

population.1

In general, as airway

obstruction increases, the prognosis of a patient with COPD worsens, with an

increased risk of death.12 A steeper decline in PF is correlated

with a greater number of years spent smoking and a greater number of

cigarettes smoked.13 The prognosis is considered poor when there is

a rapid decline in PF tests.3 A reduced survival rate is seen in

individuals living in high altitudes.3

Treatment

The treatment for

COPD is palliative, not curative.2 It is probable that longevity

cannot be significantly improved with any treatment, except in patients with

hypoxemia who benefit from supplemental oxygen therapy.2

Smoking Cessation:

Smoking cessation, including cigarettes, cigars, and pipes, is the most

important step in the treatment of COPD, since smoking is the most common

cause.3,12 Smoking cessation can revert the decline in lung

function to values of nonsmokers.14 In fact, an aggressive smoking

intervention program has been shown to significantly reduce the age-related

decline in FEV1 in middle-aged smokers with mild airway obstruction.

14 Continuation of smoking essentially ensures that symptoms will worsen.

12 Pharmacists have a huge opportunity for counseling in the smoking

cessation arena with prescription and OTC medication intervention and patient

education.

Pharmacologic Interventions:

Medication intervention usually consists of life-long chronic therapy with

dosage adjustments and additional agents when exacerbations present. According

to the American Lung Association, bronchodilators (oral or inhaled) are

central to the symptomatic management of COPD. Additional treatment includes

antibiotics, oxygen therapy, and systemic glucocorticosteroids.15

Inhaled glucocorticosteroids continue to be studied.

Chronic systemic steroid

treatment poses the risk of serious side effects and is therefore usually

reserved for acute exacerbations. Patients with COPD should receive pneumonia

and influenza vaccines. Lung transplantation or lung volume reduction surgery

may be an option for certain individuals. In addition, treatments for alpha-1

antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency emphysema, including AAT replacement therapy (a

life-long process) and gene therapy, are being evaluated. For more information

on pharmacologic treatment guidelines for COPD, the reader is referred to the

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Diseaseguidelines at:

www.goldcopd.com.

Pulmonary Rehabilitation

A comprehensive

pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) program may lead to significant clinical

improvement by increasing exercise tolerance and reducing shortness of breath.

2 PR programs may even reduce the number of hospitalizations, although

to a lesser extent.2 It should be noted, however, that while PR

programs are aimed at improving independence and improving quality of life,

they do not improve lung function or prolong survival.2,12

Ideally, a variety of health

care professionals are required to deliver the wide range of services offered

in a comprehensive PR program. Educating patients about their disease is a key

component. Exercise training, often with oxygen, may take place at the home or

in a clinic setting and often includes stationary bicycling, stair climbing,

and walking to improve leg strength, plus weight lifting to improve arm

strength.12 Techniques are taught to decrease shortness of breath

during exercise and sexual activity. Additionally, patient evaluation and goal

setting, nutritional evaluation and counseling, psychosocial counseling

(addressing depression, anxiety, sexual activity limitations), and the

coordination of complex medical services (e.g., home visits, medical

equipment, physician visits) are also provided.2 Medication

counseling is an important and integral part of PR, since medication

nonadherence is a serious complicating factor in COPD management.2

Education regarding the appropriate dosing and timing of regularly scheduled

and as-needed medications, the proper technique for self-administering inhaled

medications, ongoing monitoring, and information for family members and

caregivers is imperative.

End-Stage Disease

Mechanical

ventilation may be necessary for short- or long-term use; some individuals may

become dependent on a ventilator until death.12 Quality of life is

diminished with mechanical ventilation due to the patient