US Pharm. 2022;47(10):15-16.

Autoimmune Disease Affecting Nerves

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is an autoimmune disease in which the body’s immune system attacks its nerve receptors in the muscles. It affects between 35,000 and 60,000 individuals in the United States. MG has a higher prevalence in women when the onset is before age 40 years but a higher prevalence in males aged older than 50 years. The most common symptom is generalized muscle weakness affecting the eyes, throat, arms, and legs. It can also affect the muscles of the respiratory system. With treatment, those with MG can improve symptoms and live without significant disability.

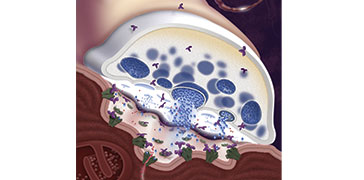

Triggers Acetylcholine Receptor Disconnect

Acetylcholine (ACh) is the neurotransmitter responsible for causing the muscles to contract and relax. Released at the end of motor nerves, ACh attaches to receptors in the muscles, completing the signal and causing muscle contraction. In MG, antibodies created by the body’s immune system harm the receptors for ACh in the muscles, triggering a disconnect. This disruption is the cause of the muscle weakness seen with MG.

Muscle weakness associated with MG fluctuates in severity. It worsens with physical activity and improves after rest. The muscle weakness of MG can be more noticeable in the afternoon or end of the day after the stores of ACh in the muscles have been depleted.

The muscles most commonly affected lead to the typical symptoms. Weakness in the eyes and eyelid muscles causes droopy eyelids and double vision. Difficulty making facial expressions is due to weakness in facial muscles. Problems swallowing or chewing and slurred speech result from weakness in the throat muscles. Generalized weakness in the arms, legs, and neck muscles are also commonly experienced by individuals with MG.

MG Diagnosis Clear, Cause Unclear

It is not clear what causes the autoimmune response that leads to MG. Many believe it can be precipitated by various factors such as infections, surgery, immunization, heat, emotional stress, pregnancy, drugs (commonly aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, beta-blockers, and neuromuscular blocking agents), and worsening chronic illnesses.

The thymus gland plays a significant role in the disease. The thymus is a small gland in the lymphatic system that makes and trains special white blood cells called T cells. The T cells help the immune system fight disease and infection. For some with MG, the thymus is removed, which significantly improves symptoms.

The first step in diagnosis is performing antibody tests to identify the presence of ACh or muscle-specific tyrosine kinase antibodies that cause MG. Some people do not have detectable antibodies, and in those cases muscle response and neurologic testing aid in diagnosing MG.

Treatment Goal Is Remission

MG is a chronic disease without a known cure. With treatment, many people with MG can achieve remission of symptoms. The Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America divides those with MG into five groups based on clinical features and symptom severity. These groups also guide the treatment approach, as they all have different prognoses and responses to therapy.

Improvement in muscle-weakness symptoms is achieved with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. These medications increase the level of ACh available at the neuromuscular junction. Pyridostigmine bromide is the most frequently used ACh inhibitor. The most common side effects experienced are abdominal cramping, diarrhea, muscle twitching, and muscle cramping. Immunosuppressants such as corticosteroids are used to control the immune response and reduce inflammation.

For individuals with AChR+ antibodies, three new drugs that target specific parts of the immune system have been approved for the treatment of generalized MG: Soliris (eculizumab), Ultomiris (ravulizumab-cwvz), and Vyvgart (efgartigimod alfa-fcab).

The content contained in this article is for informational purposes only. The content is not intended to be a substitute for professional advice. Reliance on any information provided in this article is solely at your own risk.

To comment on this article, contact rdavidson@uspharmacist.com.