US Pharm. 2006;31(11)(Diabetes suppl):21-30.

Children

have historically been heavily impacted by diabetes. In the early decades of

the last century, before diabetes was recognized as being not one but many

distinct endocrine disorders, children were among the most frequently

diagnosed with those disease. Terms such as juvenile diabetes and

childhood-onset diabetes were used to describe what is now known as type 1

diabetes mellitus (DM). More recently, the number of children diagnosed with

type 2 DM, a disease formerly thought to be exclusive to adults, has exploded.

Diabetes is one of the most frequently diagnosed chronic diseases in children,

with more than 175,000 persons in the United States younger than 20 years

having some form of diabetes.1

Pharmacists have always been

integrally involved in the care of children with diabetes. For example, when

the Durham-Humphrey Amendment, enacted in 1951, defined the medications

requiring a physician's prescription, insulins were specifically excluded in

order to allow pharmacists to dispense these live-preserving treatments

without prior authorization. More recently, the Asheville Project diabetes

program, clinics that have pharmacotherapists on staff, and community

pharmacyñbased diabetes self-education classes highlight the continuing role

of pharmacists in caring for patients with diabetes. This review familiarizes

pharmacists with the many aspects of diabetes care relevant to children and

adolescents living with diseases in this family.

Type 1 DM in Children

Type 1 DM, or

insulin-dependent DM, is an autoimmune disease involving pancreatic

beta-cell destruction and resultant insulin-production deficiency. This

disease accounts for approximately 5% to 10% of all cases of diabetes.In the

U.S., its average age of onset is 14 years.2 The rate of beta-cell

destruction is variable but appears to be faster in young children than in

older patients. As a result, ketoacidosis is more likely to be the presenting

problem among children and adolescents at time of diagnosis than it is among

adults.3

Type 1 DM is treated with

multiple daily insulin injections (either three or four times a day) or with

basal/bolus insulin infusion devices (insulin pumps).3 Due to the

complexity of the interactions between glucose and insulin, meals, and

exercise, children with type 1 DM must test their blood glucose levels very

frequently. Even small changes in any of these factors can have a dramatic

impact on blood glucose, resulting in dangerously high or low levels. Children

should be counseled to check their blood glucose as directed by their

clinician and to pay special attention to readings taken when their daily

routine is changed. They should never miss meals or insulin doses, and they

should monitor blood glucose levels before and after exercise. Those with a

history of exercise-induced hypoglycemia or those participating in endurance

events should be counseled to check their glucose levels during exercise.

A less common variant of type

1 DM, idiopathic type 1 (or Flatbush) DM is diagnosed most often in

young African-American or Asian men. It is similar to autoimmune type 1 DM in

its clinical presentation but differs in that it is not associated with

detectable beta-cellñdestroying antibodies.2 The main clinical

difference between autoimmune type 1 DM and idiopathic type 1 DM is that those

with the idiopathic variant may have waxing and waning insulin production for

years after diagnosis, and as a result, frequent insulin dose adjustments are

needed.

Insulin Pump Therapy for

Type 1 DM:Insulin

delivered continuously through an insulin pump is an extremely successful

strategy for intensive diabetes management and is gaining widespread

acceptance in the U.S. Insulin pump therapy simulates the function of

beta-cells more closely than do multiple daily injections.3 An

insulin pump delivers a constant basal insulin infusion and has the ability to

deliver larger insulin boluses around mealtimes. The bolus rate and size can

be altered depending upon caloric intake, expected activities, and other

situations (e.g., illness, emotional trauma) that can impact insulin demands.

The many advantages of insulin pump therapy include better insulin

pharmacokinetics, individualization of insulin therapy, and greater freedom in

timing of meals. The use of insulin pump therapy requires great motivation for

frequent blood glucose monitoring, carbohydrate counting, and regular medical

visits. The use of insulin pump therapy among children with type 1 DM is

predicted to increase along with expanded insurance coverage.

Type 2 DM in Children

Once thought of as

adult-onset DM, type 2 DM is becoming more common in children and

adolescents; however, the significance of this increasing prevalence may be

underestimated, as the disease may be difficult to diagnose or confused with

other types of diabetes in children.4 The increase in type 2 DM in

children parallels the continued increase in overweight and obesity in the

U.S. In late 1970s, about 4% of children were overweight, compared to more

than 17% of children in 2004, with Mexican-American boys and girls and

African-American girls at greatest risk for overweight.5

Diagnosing type 2 DM is

difficult, since children are often asymptomatic or unaware of their symptoms.

Clinicians must rely on family history and physical parameters to consider

testing for type 2 DM and laboratory information for the diagnosis.4

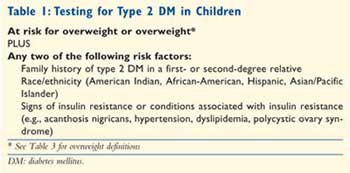

Criteria for testing children and adolescents for type 2 DM are described in

Table 1.

Correctly classifying a

child's diabetes type is critical to initiating appropriate treatment. The

predominant dysfunction in type 2 DM is insulin resistance.4

Therefore, medications that increase insulin sensitivity are most useful for

the treatment of this disease.

Lifestyle modification with

dietary intervention and physical activity are the primary management

strategies of type 2 DM in children. Depending on the severity of disease,

metformin (FDA approved for children 10 years and older) and/or insulin (at

bedtime, twice a day, or multidose regimens) may be the initial drug

treatment(s) in children with type 2 DM. For example, a child with

symptomatic, severe disease may begin insulin for most effective diabetes

control, followed by a titration to an oral medication. Conversely, a child

with asymptomatic but uncontrolled diabetes may use metformin initially. The

benefits of metformin over other oral agents for treatment of diabetes are a

decreased risk of hypoglycemia and possible weight and cholesterol reduction.

Clinical trials are evaluating thiazolidinediones in children; these agents

may eventually gain a role in the management of type 2 DM in children.6

Diabetes Complications and Concurrent

Diseases

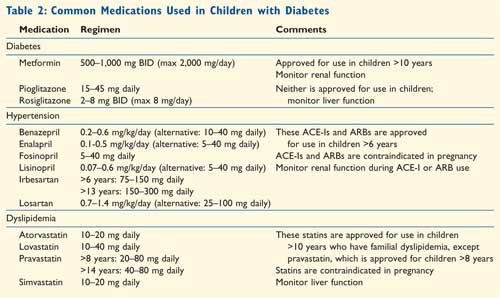

Many children and adolescents with diabetes may have microvascular complications and/or cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors. Control of weight, glucose, lipids, and blood pressure in children is necessary to prevent or delay development of complications and diseases.4 Common medications used to treat diabetes and associated diseases in children are listed in Table 2.

Diabetic retinopathy is damage

to blood vessels in the retina that eventually leads to vision loss and

blindness. Retinopathy may occur in both types of diabetes, although it is

found more frequently in children with type 1 DM than in those with type 2 DM.

7 Children with good glycemic control can be screened for retinopathy

every two years beginning at age 10 years and once the child has had type 1 DM

for three to five years. Adolescents with poor glycemic control, diabetes for

more than 10 years, or diagnosed retinopathy need more frequent screening.

8

Diabetic nephropathy is the

most common cause of chronic kidney disease in the U.S. Nephropathy may occur

more frequently in children with type 2 DM than in those with type 1 DM.7

Screening for microalbuminuria is recommended annually for both types of

diabetes beginning at the time of diagnosis of type 2 DM and beginning at age

10 years and once the child has had type 1 DM for five years.9

Screening should begin earlier (one year after diagnosis) for type 1 DM

diagnosed during adolescence, since puberty is an independent risk factor for

microalbuminuria.9 Confirmed elevated microalbumin levels may be

treated with angio!= tensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-Is), although

extreme caution is necessary when these agents are prescribed for sexually

active female adolescents due to the risk of fetal abnormalities.

Peripheral and autonomic

neuropathy caused by nerve damage occur at similar rates in children with type

1 or type 2 DM.7 Annual foot examinations should begin at puberty.

4

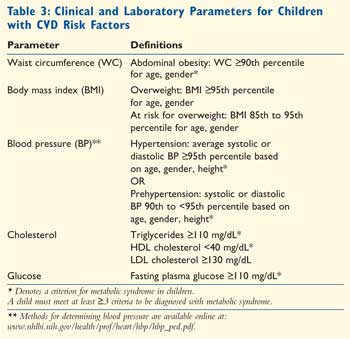

CVD risk factors are

prevalent in both types of diabetes, although a large waist circumference,

hypertension and high triglyceride and low HDL-cholesterol levels (National

Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III metabolic syndrome

criteria) occur at least three times more frequently in children and

adolescents with type 2 DM.10 Abdominal obesity and/or overweight

may directly impact the development of type 2 DM, hypertension, and

dyslipidemia.4 The clinical and laboratory parameters for CVD risk

factors are found in Table 3.

Dietary intervention and

physical activity, possibly along with pharmacologic therapy, are necessary to

prevent or delay the development of and to treat CVD risk factors.11

ACE-Is (or approved angiotensin II receptor blockers [ARBs]) are considered

first-line agents for treatment of hypertension in children with diabetes.

12 Pharmacologic treatment for prehypertension should be initiated if

goal blood pressure is not attained after three to six months of lifestyle

modifications.12 A fasting lipid panel should be obtained at

diagnosis once glucose control is established and followed every two years for

type 2 DM and every five years for type 1 DM if LDL† cholesterol remains at or

below 100 mg/dL.13

Management with statins is

indicated in children 10 years and older who are not at goal after six months

of lifestyle modification and have an LDL cholesterol level of at least 160

mg/dL, or 130 to 160 mg/dL with other CVD risk factors.13 Again,

fetal abnormalities may occur if statins are used in sexually active female

adolescents who become pregnant; thus, contraception is mandatory.

Emotional Impact of Diabetes

Regardless of age, children

diagnosed with diabetes often face tremendous emotional stress. Many of these

negative emotional effects are amplified in children and adolescents. They may

think themselves to be markedly different from their peers, a situation that

can lead to self-doubt and self-imposed isolation. It has been shown that

children with diabetes have a twofold increase in rates of depression, and

adolescents have a threefold increase, compared to those without diabetes.

14 Children with concurrent diabetes and depression have a tenfold

increase in suicide and suicidal ideation.14

Typically, a child diagnosed

with diabetes will report mild depression and anxiety immediately following

diagnosis, with resolution of these complaints six to 12 months later. These

depressive symptoms often return in one to two years. While boys usually lose

anxiety symptoms during the six years following diagnosis, girls often

demonstrate an increase in anxiety.3

Aside from the overall

negative impact of depression upon youth, depression negatively impacts

diabetes control. One recent study found that adolescents ages 13 to 18 with

psychiatric comorbidities had a significantly higher rate of diabetes-related

hospitalization than did those without.15 Interestingly, this

difference was not significant among younger children, which points toward the

greater impact of mood disorders among adolescents.

An important consideration

when treating a child with diabetes is appropriate self-management by age.

3 As children develop, it is important to allow them to accept more

responsibility for their own nutritional intake, monitoring, and treatment. A

child who is never allowed to care for himself or herself will not develop the

skills needed to cope with this lifelong disease. The pharmacist can aid in

the transition of care by always including the child and parent in educational

sessions.

Another troubling trend has

been that children entering adolescence while undergoing insulin therapy often

have body-image issues due to the adipose-forming effects of exogenous

insulin. As a result, some adolescents decrease or eliminate insulin therapy

in order to lose weight. The resultant acidosis can lead to rapid and profound

weight loss, further encouraging this dangerous activity, in the mind of the

patient. Pharmacists should pay close attention to adherence to insulin

therapy and should take notice of sudden or unexplained weight loss during the

adolescent and college years.

In addition to considering the

impact of diabetes on the mental health of the child, pharmacists should be

conscious of the emotional well-being of the parents or caregivers. For

instance, caring for an infant with diabetes dramatically increases the

already significant emotional toll on the parents.16 The complexity

of diabetes management plans and concerns of hypoglycemia may be overwhelming.

Pharmacists must take the time to question parents about their emotional and

mental health and refer for appropriate therapy as needed.

Pharmacist Involvement with Diabetes

By increasing their involvement in

caring for children with diabetes, pharmacists affirm their role as health

care leaders in the community. For instance, most regions of the country have

"diabetes camps," which provide a traditional camping experience to children

and adolescents with diabetes, in a medically supervised environment. These

camps enroll 15,000 to 20,000 children each year and can always use the

expertise of a pharmacist for dispensing medications and counseling the

children on their disease and its treatments.16 The Clinical

Practice Guidelines of the American Diabetes Association (ADA), published

every January in Diabetes Care, include guidelines for appropriate

management of these camps.17

These guidelines also include

recommendations for schools and daycare centers that enroll children with

diabetes.18 For instance, these institutions should design

individualized management plans that detail when a student may check his or

her glucose or administer medication and which activities the child may

participate in. Pharmacists can help ensure that school boards and

administrators adhere to these recommendations. The clinical practice

recommendations are available on the ADA Web site (www.diabetes.org).

Another valuable resource for

children with diabetes and their caregivers is the Children with Diabetes Web

site (www.childrenwithdiabetes.com). This site offers family support networks,

a question-and-answer forum, and recommendations for improving the quality of

life of a child with diabetes. Although this site does accept advertising, its

content is largely without commercial bias or influence, setting it apart from

many "informational" sites operated by pharmaceutical or monitoring device

manufacturers. One interesting component of this site is a set of formal

guidelines for babysitters of children with diabetes. Included are

recommendations (e.g., when and what to feed the child, when to give

medications, when to contact the parents) that should increase the comfort

level of both the parents and the babysitter.

Conclusion

Pharmacists have

ample opportunity to expand their role in the management of children and

adolescents with both type 1 and type 2 DM. A greater understanding of

diabetes and its complications along with associated CVD risk factors allows

pharmacists to become more proactive in screening, recommending and monitoring

pharmacologic therapy, and counseling children and adolescents with either

type 1 or type 2 DM. Pharmacists must also understand the emotional toll of

diabetes and be cognizant of the risk of depression in children and their

caregivers. Children with diabetes must be treated as much as possible like

children who do not have the disease in order to minimize the impact of

diabetes upon their quality of life. Beyond these standard components of

practice, pharmacists must also consider increasing their role in improving

community standards for the care of children living with diabetes.

References

1. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes (Position Statement). Diabetes Care .2006;29:S4-S42.

2. American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes (Position Statement). Diabetes Care .2006;29:S43-S48.

3. American Diabetes Association. Care of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes (Statement). Diabetes Care. 2005;28:186-212.

4. American Diabetes Association. Type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents (Consensus Statement). Diabetes Care.2000;23:381-389.

5. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999-2004. JAMA. 2006;295:1549-1555.

6. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Treatment options for type 2 diabetes in adolescents and youth (TODAY). Available from: www.todaystudy.org/medp1.cgi. Accessed March 30, 2005.

7. Eppens MC, Craig ME, Cusumano J, et al. Prevalence of diabetes complications in adolescents with type 2 compared to type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1300-1306.

8. Maguire A, Chan A, Cusumano J, et al. The case for biennial retinopathy screening in children and adolescent. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:509-513.

9. Gross JL, DeAzevedo MJ, Silveiro AP. Diabetic nephropathy: diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:164-176.

10. Rodriguez BL, Fujimoto WY, Mayer-Davis EJ. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors in U.S. children and adolescents with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1891-1896.

11. Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA. 2001;285:2486-2497.

12. National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on Hypertension Control in Children and Adolescents. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114:555-575.

13. American Diabetes Association. Management of dyslipidemia in children and adolescents with diabetes (Consensus Statement). Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2194-2197.

14. Grey M, Whittemore R, Tamborlane W. Depression in type 1 diabetes in children; natural history and correlates. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:907-911.

15. Garrison MM, Katon WJ, Richardson LP. The impact of psychiatric comorbidities on readmissions for diabetes in youth. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2150-2154.

16. Banion CR, Miles MS, Carter MC. Problems of mothers in management of children with diabetes. Diabetes Care . 1983;6:548-551.

17. Diabetes care at diabetes camps. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:S56-S68.

18. Diabetes care in the school and

day care setting. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:S49-S55.

To comment on this article, contact

editor@uspharmacist.com.