US Pharm . 2007;32(8):HS13-HS22.

Gynecomastia refers to breast enlargement in males. It may be a consequence of a serious pathologic problem or just a benign physiologic condition. The term gynecomastia is defined as an abnormal enlargement of one or both breasts and comes from the Greek word for woman's breasts. Gynecomastia may be caused by hormonal imbalance, systemic disorders, various types of carcinomas, and numerous drugs. Regardless of the cause, breast enlargement in males can lead to an embarrassing appearance and produce serious psychological stress for the patient as well as family members, especially if the patient is an adolescent. Even if the breasts are not significantly enlarged, there may be an asymmetry of the chest, which can lead to self-consciousness about this physical deformity.

Epidemiology

Gynecomastia is seen in males of all ages; however, the prevalence of gynecomastia is generally considered to be trimodal (i.e., in newborns, adolescents, and the elderly). It is found in 60% to 90% of newborns due to prenatal transfer of estrogen and is a fairly common occurrence in pubertal boys, with an incidence as high as 70%.1,2 However, the enlarged breasts usually shrink or disappear without treatment within one to three years after onset.3 Gynecomastia is also a common occurrence after age 50, when androgen production decreases as a normal result of aging, especially if there is concomitant weight gain. It is estimated that gynecomastia can affect more than 40% of postpubescent males at some time in their lives.1 Medications are responsible for about 10% to 20% of gynecomastia cases in postadolescent males. About 25% of all cases have no apparent cause.1

Etiology

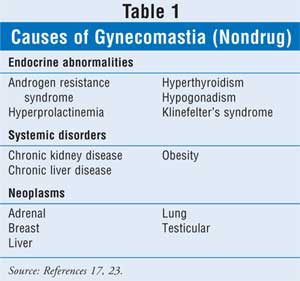

Pathologic gynecomastia is generally the result of an increase in the ratio of estrogen to androgen. Any condition that can alter this ratio can produce gynecomastia. True gynecomastia involves glandular rather than adipose tissue and is usually tender to touch. Because of its prevalence and presentation, the diagnosis of gynecomastia requires a comprehensive workup. A list of many common nondrug causes of gynecomastia can be found in Table 1.

Neoplasms: Gynecomastia can be the first sign of an adrenal, liver, lung, or testicular tumor. Many types of tumors, including small cell lung cancer and those involving the Leydig's cells of the testes, can stimulate the production of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), which in turn can increase the estrogen–androgen ratio.4,5 Conversely, gynecomastia may increase the risk of other types of cancers (e.g., testicular and squamous cell), although this risk is small.6

Glandular proliferation of the breasts can also be the result of male breast cancer; however, this is very uncommon. The American Cancer Society estimates that in 2007 there will be only about 2,000 new cases of male breast cancer.7 In addition, the number of deaths from male breast cancer represent only about 1% of those from female breast cancer.

Hormonal Imbalance: Gynecomastia is primarily a disorder of hormonal imbalance. Patients may exhibit either increased serum estrogen, decreased testosterone production (e.g., hypogonadism), or decreased tissue responsiveness to hormones. As men age, they tend to produce less testosterone and gain adipose weight. This weight gain results in increased estrogen levels due to androgen conversion to estrogens by the enzyme aromatase and, in turn, produces an increase in glandular tissue of the breasts due to the imbalance of estrogen to testosterone (elevated estrogen–androgen ratio).4,8

Decreased testosterone can also occur congenitally, as in the genetic disorder Klinefelter's syndrome.9 Mutations of the androgen receptor, such as those seen in Kennedy's syndrome, is another cause of gynecomastia.10 Diseases of the hypothalamus or pituitary tumors can also lead to gynecomastia because they can diminish testosterone levels.

Another cause of gynecomastia involving hormonal imbalance is hyperthyroidism. Thyroid hormones stimulate the liver to produce sex-hormone–binding globulin (SHBG), which leads to an increased binding of testosterone relative to estradiol. This results in a decrease in free testosterone relative to estrogen. There is also enhanced aromatization (by aromatase) of testosterone to estradiol. This increase in estradiol stimulates the liver to produce even more SHBG. Therefore, gynecomastia results from the combination of decreased free androgen levels combined with the overproduction of estrogens.11

Lastly, gynecomastia can be the result of normal aging. As men grow older, testosterone production wanes. This is referred to as primary hypogonadism. When all other causes are ruled out, this may be the most likely source of the problem.

Systemic Disorders: Chronic liver disease and kidney failure can both produce gynecomastia by affecting the body's hormonal balance. A patient with liver disease may experience an increased conversion of testosterone to estrogen as well as an elevation in serum SHBG. In renal disease, gynecomastia occurs in 50% of patients on hemodialysis, primarily due to Leydig's cell dysfunction; luteinizing hormone (LH) levels are elevated in these patients.

Medications: Although drugs are responsible for less than 20% of all cases of gynecomastia, there is a long list of medications that have been identified as potential causes of this condition (Table 2). Gynecomastia occurs because of a variety of actions depending on the drug and its chemical structure. For example, digoxin and spironolactone act like estrogen, ketoconazole acts by blocking the synthesis of androgens, flutamide stimulates estrogen production, and many other drugs, such as the tricyclic antidepressants, have an unknown mechanism of action.12-14 While the adverse effects of prescription and nonprescription drugs are fairly well documented, little is known about the relationship between dietary supplements and gynecomastia. A recent study reported three cases of gynecomastia that appeared to have been caused by the topical application of products containing lavender oil and/or tea tree oil. 15 It is believed that both of these agents have estrogenic and antiandrogenic activity. A search revealed more than 175 products containing one or both of these ingredients. Another product of concern is androstenedione, also known as andro. A precursor of testosterone, it is sold in health food stores as a natural substance designed to enhance athletic performance in males. However, due to its effects on serum estradiol and estrone, males may actually experience feminization.16

Patient Assessment

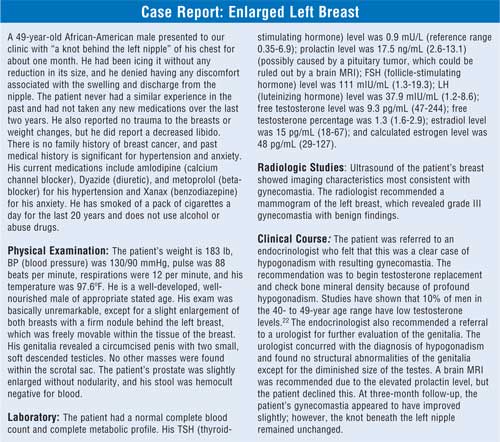

Due to the diverse causes of gynecomastia, a thorough history is crucial in determining what treatment approach is best. Because of the lack of information on dietary supplements, pharmacists and physicians need to be extra diligent in obtaining a drug history that includes natural products and nutritional supplements. The diagnostic workup of gynecomastia should include an ultrasound of the breast as well as blood levels of beta-hCG, LH, follicle-stimulating hormone, estrogen, estradiol, prolactin, testosterone; thyroid function (thyroid-stimulating hormone and thyroxine); and liver function tests. 14,17 Sometimes a referral to an endocrinologist is warranted if multiple hormone abnormalities are present. Mammography may also be indicated if the ultrasound result is not definitive.18

One condition that can easily and quickly be ruled out is pseudogynecomastia, which refers to the condition seen in overweight males who develop fatty accumulation of the breasts as opposed to the glandular proliferation seen in true gynecomastia. The distinction can readily be made during physical examination. The examiner places the thumb and forefinger at opposite margins of the breast. The fingers are then brought slowly together along the nipple line. Enlarged glandular tissue can be recognized as a rubbery to firm disk of tissue concentric to and beneath the areolar area. The tissue is often freely mobile and may be quite tender to palpation during the acute phase of development of gynecomastia.

When gynecomastia is bilateral, a hormonal origin is likely. If the condition is unilateral, the condition is more likely to be idiopathic or caused by drugs. The age and general health of the patient may also be helpful in identifying the cause. If the patient's blood work is not indicative of any specific endocrine or systemic disorder and the patient is not taking any medication implicated in gynecomastia, the cause is most likely idiopathic.

Treatment

Treatment of gynecomastia is very different from the treatment of most other conditions because it is often the result of other problems (i.e., neoplasms, hormonal imbalance, systemic diseases). The approach to gynecomastia is based on identification and treatment of the primary cause. For example, in pubertal males, the condition is primarily self-limiting, although it can take years to resolve. No specific treatment is generally required. If it is caused by a neoplasm or by thyroid, liver, or kidney disease, then these conditions need to be treated. When the primary cause is adequately treated, the breasts should shrink in size after several months of treatment, although they may not completely return to normal.

In the case of drug-induced gynecomastia, treatment consists of discontinuation of the suspected drug. In these cases, pharmacists should be ready to recommend alternative drugs to the prescribing physician. Discontinuation of the offending medication may also lead to regression of gynecomastia, but not always.

When the patient experiences pain or is unable to undergo any other type of treatment, selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs)(antiestrogens), such as tamoxifen or raloxifene, have been used. They have been reported to be effective in producing pain relief and reducing breast size in two out of three patients.4 Since gynecomastia is a common side effect seen in prostate cancer patients taking antiandrogens such as bicalutamide (Casodex), tamoxifen is one of the drugs used to counter the breast enlargement and pain caused by the treatment.17 Aromatase inhibitors, such as anastrozole (Arimidex) and letrozole (Femara), are being considered as potential treatments for gynecomastia.4,20,21 Other drugs, such as the SERM clomiphene, are being investigated for the treatment of hypogonadism, which can induce gynecomastia.24

Unlike pseudogynecomastia, weight loss may not completely reverse true gynecomastia since it is a glandular abnormality, despite the fact that breast enlargement may have been triggered by the estrogen conversion pathway. The longer the patient has gynecomastia, with the exception of pubertal males, the less likely it will resolve completely. As time goes by, breast tissue becomes more fibrous. In these cases, surgery may be the only other treatment option.14

If a patient is diagnosed with hypogonadism with low testosterone, then testosterone replacement to mid/normal testosterone levels is indicated.4 Oral testosterone is not recommended because appropriate blood levels cannot be attained. Oral testosterone derivatives such as oxandrolone and fluoxymesterone produce too many serious adverse effects, including hepatotoxicity.4 Recommended routes of administration include injection (intramuscular), skin transdermal patch (Androderm), scrotal transdermal patch (Testoderm), topical gel (Androgel,Testim), buccal adhesive tablet (Striant), and subcutaneous implantable pellets (Testopel).

Patient Counseling

Pharmacists can assist patients in a number of different ways. When counseling a male patient on the use of a new medication that has the potential to produce gynecomastia, such as amitriptyline, the pharmacist should thoroughly explain the nature and significance of this problem. It is also very important to remind the patient that the incidence is low for most drugs. Although the problem is reversible upon discontinuation of the medication, the patient should contact his physician before stopping the medication on his own.

Pharmacists should also be ready to refer to a physician any male patient who expresses concern about breast enlargement, tenderness, and/or pain. These signs and symptoms may indicate anything from self-limiting gynecomastia to a systemic neoplasm.

Because of the embarrassment of breast enlargement in males, especially in adolescents, patients may appear to be depressed or unwilling to talk about their feelings. Referral to an appropriate health care provider would be in order. Also, there are several organizations that provide free patient education materials through their Web sites.

References

1. Braunstein GD. Gynecomastia. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:490-495.

2. Braunstein GD. Testes. In: Lange Endocrinology. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2007. Available at: www.accessmedicine.com.cuhsl.creighton.edu/content.aspx?aID= 2630788&searchStr=gynecomastia#2630788. Accessed June 13, 2007 (subscription only).

3. Patton DD, Harris JR. Adolescent development & screening. In: Current Family Medicine . New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2007. Available at: www.accessmedicine.com/content.aspx?aID=868838&searchStr=gynecomastia#868838. Accessed June 13, 2007.

4. Bhasin S, Jameson JL. Disorders of the testes and male reproductive system. In: Harrison's Online. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2007. Available at www.accessmedicine.com.cuhsl.creighton.edu/content.aspx?aID=99605. Accessed June 17, 2007 (subscription only).

5. Yaturu S, Harrara E, Nopajaroonsri C, et al. Gynecomastia attributable to human chorionic gonadotropin-secreting giant cell carcinoma of lung. Endocr Pract. 2003;9:233-235.

6. Olsson H, Bladstrom A, Alm P. Male gynecomastia and the risk of malignant tumours--a cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2002;2:26. Available at: www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2407/2/26. Accessed June 17, 2007.

7. American Cancer Society. What are the key statistics about breast cancer in men? Available at: www.cancer.org/docroot/CRI/content/CRI_2_4_1X_What_are_the_key_statistics_for_male_breast_cancer_28.asp?rnav=cri. Accessed June 13, 2007.

8. Chabner BA, Amrein PC, Drucker BJ, et al. Antineoplastic Agents. In: Goodman & Gilman's Pharmacology. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2007.

9. Achermann JC, Jameson JL. Disorders of sexual differentiation. In: Harrison's Online . New York: McGraw-Hill; 2007. Available at: www.accessmedicine.com/ content.aspx?aID=100318. Accessed June 17, 2007.

10. Kennedy WR, Alter M, Surg JH. Progressive proximal spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy of late onset. A sex-linked recessive trait. Neurology. 1968;18:671-680.

11. Anderson DC. Sex-hormone-binding globulin. Clin Endocrinol. 1974;3:69-96.

12. Chrousos GP. The gonadal hormones & inhibitors. In: Lange Pharmacology. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2007.

13. Thompson DF, Carter JR. Drug-induced gynecomastia. Pharmacotherapy. 1993;13:37-45.

14. Fawzi A, Bain J. Gynecomastia. In: Paletta C, Talavera F, Shenaq SM, et al., eds. The eMedicine Clinical Knowledge Base, Institutional Edition. WebMD; 1996-2006. Available at: www.imedicine.com.cuhsl.creighton.edu/DisplayTopic.asp?bookid=15&topic=125. Accessed June 14, 2007 (subscription only).

15. Henley DV, Lipson NL, Korach KS, et al. Prepubertal gynecomastia linked to lavender and tea tree oils. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:479-485.

16. King DS, Sharp RL, Vukovich MD, et al. Effect of oral androstenedione on serum testosterone and adaptations to resistance training in young men. JAMA. 1999;281: 2020-2028.

17. Papadakis MA, McPhee SJ. Gynecomastia. In: 2007 Current Consult: Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2007. Available at: www.accessmedicine.com/content.aspx?aID=2579909&searchStr=gynecomastia. Accessed June 13, 2007.

18. Hines SL, Tan WW, Yasrebi M, et al. The role of mammography in male patients with breast symptoms. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:297-300.

19. Di Lorenzo G, Autorino R, Perdona S, De Placido S. Management of gynaecomastia in patients with prostate cancer: a systematic review. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:972-979.

20. Riepe FG, Baus I, Wiest S, et al. Treatment of pubertal gynecomastia with the specific aromatase inhibitor anastrozole. Horm Res. 2004;62:113-118.

21. Dobs A, Darkes MJ. Incidence and management of gynecomastia in men treated for prostate cancer. J Urol. 2005;174:1737-1742.

22. Greenspan SL, Resnick NM. Geriatric endocrinology. In: Lange Endocrinology. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2007. Available at: www.accessmedicine.com.cuhsl.creighton.edu/content.aspx?aID=99846&searchStr=hypogonadism#99846. Accessed June 17, 2007 (subscription only).

23. Fitzgerald PA. Endocrinology. In: Current Medical Dx & Tx. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2007. Available at: www.accessmedicine.com/content.aspx?aID=14225&searchStr=gynecomastia. Accessed June 13, 2007.

24. Shabsigh A, Kang Y, Shabsign R, et al., Clomiphene citrate effects on testosterone/estrogen ratio in male hypogonadism. J Sex Med. 2005;2:716-721.

To comment on this article, contact editor@uspharmacist.com.