US Pharm.

2007;32(10)(Diabetes suppl):10-16.

Diabetes is a major public health problem

that affects 7% of the United States population, or 20.8 million people.1

Type 2 diabetes accounts for 90% to 95% of the diabetes population and is

diagnosed with increasing frequency, especially in adolescents and children.

Nearly one third of individuals with diabetes are unaware of their illness,

which delays the time to treatment and increases the risk of complications.

Also, the cost of diabetes is staggering, with over $100 billion per year

spent on the treatment of people with this disease.

Diabetes is the leading cause of

adult blindness, nontraumatic amputations, and end-stage renal disease. In

addition, the death rates associated with heart disease and the risk of stroke

are about two- to fourfold higher in adults with diabetes. These macrovascular

complications account for 65% of deaths in people with the disease.1

Studies have documented that maintaining glycemic levels as close to normal

as possible helps to reduce diabetes-specific complication risks.2-4

Each percentage point reduction in hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c)--equal to a drop in

average plasma glucose of about 40 mg/dL--reduces the risk of microvascular

disease by 37%.4 These observations have led to intensification of

glycemic targets. The American Diabetes Association currently recommends that

each patient maintains glycemic levels as close to normal as possible (HbA1c

<6%) and minimally below 7%.5

Pathophysiology

Normal physiological insulin

secretion consists of a continuous basal secretion to control fasting and

between-meal glucose and postprandial spikes in insulin to control

meal-related hyperglycemia. Type 2 diabetes is characterized by insulin

resistance and dysfunction in pancreatic beta- and alpha-cell function,

resulting in increasing insulin deficiency and increased glucose levels.6

By diagnosis, pancreatic beta-cell function is only 50% that of a healthy,

nondiabetic individual. Pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction in type 2 diabetes is

progressive, which often necessitates insulin therapy as insulin levels wane.

Several diabetes medications, including thiazolidinediones (TZDs) and incretin

therapy, may slow the deterioration of pancreatic beta-cell function, but

confirmatory data in humans is needed. Pathophysiologically, high fasting

plasma glucose (FPG) levels result from excessive hepatic glucose production

while postprandial glucose (PPG) levels are dependent upon multiple factors,

including muscle insulin resistance, relative insulin deficiency, meal

carbohydrate intake, and incretin deficiency.7 The contribution of

the FPG to an HbA1c is greater when HbA1c levels are higher; however, as HbA1c

values approach normal, PPG plays a greater role in determining HbA1c levels.

8

Many treatment options are now available to

treat type 2 diabetes. Importantly, in the new treatment paradigm, insulin is

no longer the "treatment of last resort" to be used after multiple oral

antidiabetic agents (OADs), but rather, whenever insulin is needed to achieve

target glycemic levels (goal-oriented therapy). This article provides

pharmacists with an overview of recent developments and currently available

insulin therapies in the management of type 2 diabetes.

Misconceptions About Insulin

Therapy

Insulin has greater glucose-lowering potential than any other current diabetes

therapy, and the maximal dose is limited only by the potential for

hypoglycemia. Insulin alleviates the glucotoxicity and lipotoxicity that occur

with poorly controlled diabetes and may improve pancreatic beta-cell function

in recently diagnosed patients with type 2 diabetes.6,9,10 Still,

patients and their physicians are often reluctant to initiate insulin therapy

because of concerns about hypoglycemia, weight gain, and injections. Both may

view the start of insulin therapy as a failure to adhere to recommendations

for lifestyle modifications and medications. This delays advancement to

insulin therapy and can increase the risk of long-term complications. These

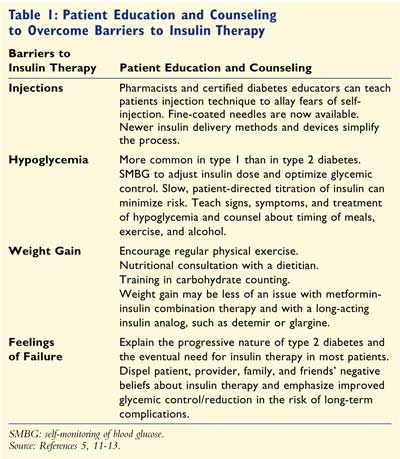

barriers can be overcome with provider and patient education--beginning

at the time of diagnosis and reinforced when needed5,11-13 (TABLE

1).

Patient Selection for Insulin Therapy

Insulin therapy is indicated in patients with type 2 diabetes when they have

symptomatic hyperglycemia (such as weight loss, dehydration, or extreme

thirst), when they are pregnant, or when their glycemic control is poor

despite current therapy.14,15 In newly diagnosed individuals,

insulin may be initiated on a short-term basis to overcome high glucose levels

(glucose toxicity), which severely reduces the amount of insulin the

beta-cells can produce.14 Patients already taking OADs and with an

HbA1c higher than 8.5% are candidates for insulin, as addition of another OAD

or incretin-based therapy will likely reduce HbA1c by only 1% to 1.5%, failing

to reach glycemic goals.16 Concurrent inpatient medical conditions

such as myocardial infarction, stroke, infections, trauma, or surgery may

necessitate short-term use of insulin in type 2 diabetes.17

Types of Insulin

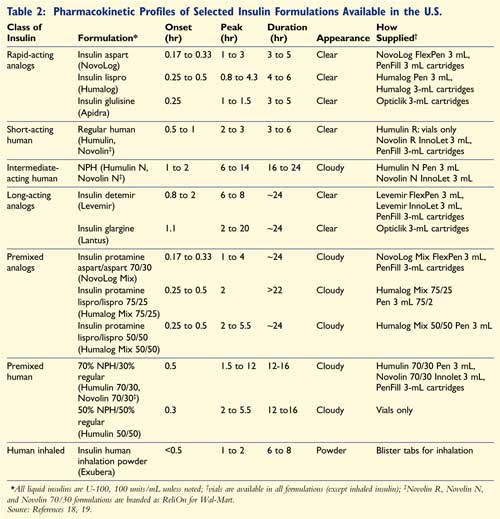

The two main types of injectable

insulins available are human insulins and insulin analogs. These are further

divided based on their formulation, onset, and peak of action into

rapid-acting, short-acting, intermediate-acting, long-acting, and premixed (

TABLE 2).18,19 The recently introduced inhaled human insulin

(Exubera) has onset and peak characteristics similar to rapid-acting insulins

and a duration of action similar to regular human insulin.20 It is

recommended that pulmonary function tests be used to monitor patients on

inhaled insulin at baseline, six months, and yearly thereafter.21

Smokers, individuals with pulmonary diseases, and patients with asthma are not

candidates for this therapy.20

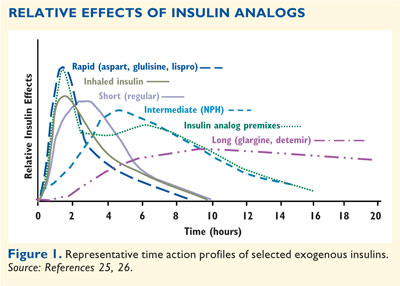

Insulin Analogs:

Insulin analogs have been formulated to have advantages over human insulin

formulations in pharmacokinetics, efficacy, safety, and/or convenience of

dosing (FIGURE 1).22-26 Peak insulin action occurs more

rapidly with rapid-acting insulin analogs and premixed insulin analogs when

compared to regular insulin or premixed human insulin, respectively.9

The quicker onset of action allows more convenient dosing (i.e., within 15

minutes of a meal for analogs versus at least 30 minutes prior for regular

insulin) and potentially offers better mealtime hyperglycemia control.9

The increased duration of effect (up to 24 hours) with the long-acting

insulin analogs allows once-daily dosing in type 2 diabetes, and their

time-action profiles are relatively flat when compared with neutral protamine

Hagedorn (NPH) insulin, which has a definite peak and approximate 12-hour

duration of action.24 Less within-patient variability ("wobble" of

insulin levels between multiple injections) is reported with the insulin

analogs than with human insulin.24 This may explain why long-acting

analogs appear to cause less severe or nocturnal hypoglycemia.23,27

The full magnitude of the benefits of insulin analogs may become clearer as

long-term safety and efficacy data become available.28

Algorithms for Insulin Therapy

Various

professional associations have developed different algorithms for treating

type 2 diabetes. The American College of Endocrinology and the American

Association of Clinical Endocrinologists list insulin as the preferred

treatment when the HbA1c is 10% or higher.5,29 In patients

previously treated with OADs, insulin may be added whenever indicated, but

especially if the HbA1c is greater than 8.5%. The Texas Diabetes Council

Algorithm recommends insulin for treatment-naïve patients with a FPG of at

least 260 mg/dL or an HbA1c of at least 10%. For patients on OADs and with an

HbA1c of 8.5% or less, once-daily insulin is the treatment of choice, although

if their HbA1c levels are above 8.5% a multidose insulin regimen is

recommended.30

Insulin Regimens

The optimal insulin

regimen for a patient allows them to reach glycemic goals, limits

hypoglycemia, and fits their lifestyle. Factors to consider in tailoring an

individual insulin regimen include current glycemic control, need for fasting

and/or postprandial coverage, lifestyle requirements, concomitant disease

states such as renal or liver disease, and the OADs that will be continued in

their treatment regimen.9 Metformin and TZDs improve hepatic and

peripheral insulin sensitivity and often result in a substantial reduction in

the insulin dose necessary for glycemic control.22,31,32 Patients

receiving both insulin and metformin gain less weight than patients on insulin

alone or TZD plus insulin combination therapy.32 Patients who

continue TZDs with insulin should be monitored for weight gain, peripheral

edema, and increasing shortness of breath, all potentially limiting factors

that may necessitate discontinuation of TZD use.22 Sulfonylureas or

meglitinides may be continued at the time of initiation of once-daily basal

regimens but should be discontinued with intensification of insulin therapy.

16 Many clinicians are successfully using exenatide or dipeptidyl

peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors in combination with insulin, but neither is

currently FDA approved for combination with insulin.

Initiating Insulin Therapy

Adding a basal or

premixed insulin to OADs is the simplest way to start insulin therapy.9

In a 24-week trial, the once-daily insulin analog glargine had a similar

efficacy to NPH insulin (both were in combination with OADs) in achieving

targeted HbA1c levels. Nearly 60% of patients achieved target HbA1c levels of

less than 7%, but 25% more patients treated with insulin glargine achieved the

HbA1c goals without nocturnal hypoglycemia.27 A similar 26-week

trial comparing insulin detemir with NPH as add-on therapy to OADs noted HbA1c

levels of 7% or lower in 70% of all patients, although this was achieved

without incidence of hypoglycemia in significantly more patients treated with

insulin detemir compared to those treated with NPH (26% vs. 16%, respectively;

P = .008).23 Additionally, patients using insulin detemir and OADs

experienced significantly less weight gain, a 47% decrease in all

hypoglycemia, and a 55% decrease in nocturnal hypoglycemia compared with

patients using NPH insulin and OADs.23 A 52-week open-label trial in

diabetes with type 2 diabetes who were poorly controlled on OADs

compared the addition of insulin glargine daily or insulin detemir once or

twice daily. Insulin detemir and insulin glargine resulted in similar A1C

control and risk of overall and nocturnal hypoglycemia.33

Whereas long-acting basal

insulins can normalize the FPG, they do little to control PPG. Premixed

insulin formulations may be useful in patients who need to cover both

uncontrolled FPG and PPG. Patients with type 2 diabetes who were taking

metformin and NPH were randomized to metformin in combination with either

insulin lispro 75/25 (Humalog Mix 75/25) twice daily or

insulin glargine daily. Insulin lispro 75/25 reduced PPG significantly more

than insulin glargine after all three meals (P <.001), whereas insulin

glargine resulted in significantly lower FPG levels (7.39 vs. 7.90 mmol/L; P =

.007).34 The average daily insulin dose was slightly higher in the

insulin lispro 75/25 group due to the ability of the premixed insulin analog

to target both FPG and PPG, ultimately resulting in the significantly lower

HbA1c levels observed at the end of the trial.34 In insulin-naïve

patients with type 2 diabetes who were poorly controlled on OADs, twice-daily

biphasic insulin aspart 30 (Novolog Mix 70/30), which could be titrated to

0.82 U/kg/day by targeting FPG and PPG, was more effective than once-daily

insulin glargine titrated to 0.55 U/kg/day. More patients achieved an HbA1c of

7% or lower with biphasic insulin aspart 30 compared with insulin glargine

(66% vs. 40%, respectively; P <.001), but the higher dose of insulin was

accompanied by increased minor hypoglycemia and weight gain.35 The

1-2-3 Study reported that biphasic insulin aspart 30 administered once with

the evening meal, twice daily at breakfast and evening meal, or three times

daily with the third injection at lunch, advanced as needed to obtain glycemic

control, allowed 41%, 70%, and 88% of the participants, respectively, to

achieve a target HbA1c of less than 7%.36

As an alternative to

premixed insulins, patients currently on one injection of long-acting insulin

analogs requiring prandial coverage can add a rapid-acting or short-acting

insulin prior to the largest meal of the day. If HbA1c levels are still above

goal, a second injection of prandial insulin can be given prior to the second

largest meal. Basal-bolus insulin regimens (using four to five injections per

day or an insulin pump) best mimic physiological insulin release and offer the

most flexibility for patients with variable exercise and eating habits.9

Appropriate self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) is required based on the

insulin regimen chosen. Carbohydrate counting may also help to optimize

glycemic control, but is an advanced skill and requires education from a

skilled diabetes educator in conjunction with a motivated patient. In the

PREFER study, an HbA1c lower than 7% was achieved by 50% of patients with type

2 diabetes taking biphasic insulin aspart 30% and 60% of patients taking

insulin detemir/aspart as basal-bolus

therapy.37

Titrating Insulin

To normalize the

FPG with long-acting basal insulin, it is safe to start empirically at 10

units daily or at a low dose of 0.15 U/kg/day.9 Patients should

titrate the dose 2 units at a time every two to three days, based on SMBG,

until the FPG is at goal. A more aggressive starting dose for patients failing

current therapy and an HbA1c above 8.5% would be 0.3 U/kg. Alternatively, the

treat-to-target concept uses titration schedules based on specific algorithms

starting with 10 units once daily and unit adjustments based on SMBG, managed

by the patient with guidance, to bring the FPG to goal.27 Also, one

injection of premixed insulin with the evening meal can be started at doses

similar to basal insulin but should be titrated based on bedtime as well as

fasting SMBG readings. PPG reduction is achieved with bolus doses of prandial

insulin given at mealtimes and titrated by two-hour postprandial or the next

premeal SMBG readings.

In

a twice-daily premixed regimen, the starting dosage may range from 0.3 to 0.5

U/kg/day or can be empirically started at 10 units with the morning and

evening meal.9,30 SMBG and mealtime carbohydrate distribution are

used to guide titration; a larger dose can be given with the larger meal. When

titrating premixed insulin, it is imperative that the correct insulin

injection be adjusted to obtain HbA1c goals The evening premixed insulin dose

should be increased if the fasting SMBG is high, whereas the morning premixed

insulin dose should be increased if the pre-evening meal SMBG is high.

Incorrectly increasing the dose of insulin at the same time that the SMBG is

high can lead to hypoglycemia (e.g., increasing the insulin dose in the

evening if the pre-evening meal SMBG is high).9

Education of the Patient

Patient counseling at every point of contact with the health care team helps

to increase patient comfort when insulin therapy is started. This starts at

the time of diagnosis by explaining to patients that insulin will likely be

necessary because of the progressive beta-cell deterioration and not because

of their failure to manage the disease. Educating patients and caregivers

about hypoglycemia prevention and treatment is a priority, since the condition

can undermine patient confidence and, when severe, is potentially dangerous.

Additionally, ensuring that the patient can and will do SMBG monitoring at the

appropriate times is helpful, as is a review of injection technique.

Unopened vials of

insulin should be refrigerated but never frozen.11 Once opened,

insulin vials can generally be kept at room temperature (below 86°F) for a

month or more depending on the formulation. Insulin pens may have a shorter

expiration, and it is important to note this to the patient and dispense the

correct number of pens per month based on the expiration.19 Inhaled

insulin blisters are stable at room temperature and have a three-month

expiration once the foil package is opened.19 Thus, it is advisable

to check the storage instructions for each insulin preparation before

counseling the patient. Refrigerated insulin should be allowed to reach room

temperature before injecting to prevent unwanted delays in absorption and

redness, welts, or stinging at the injection site. Additionally, ensure that

suspension formulations of insulin are resuspended by the patient prior to

drawing a dose of insulin from a vial or injecting insulin with a pen device.

18

Manipulation of or a rapid change in temperature at the injection site can

change the kinetics of the insulin. For example, a hot bath or jogging

immediately following an insulin injection in the leg may cause a faster

systemic uptake of the insulin, whereas cold temperatures may have the

opposite effect.11 Excessive alcohol consumption, especially in

type 1 diabetes, may increase the risk of delayed or nocturnal hypoglycemia.

11 Concurrent use of other medications that affect blood sugar, such as

corticosteroids, warrant careful monitoring and adjustment of insulin dose.

17

Insulin delivery devices, such as insulin pens, may help patients who are

worried about eating out, varied meal times, social discretion, or portability

issues, compared to traditional vials and syringes.12 Some pens are

disposable while, others use replaceable insulin cartridges (see TABLE 2,

available in the online version of this article). Pens may have an audible

click for each unit of insulin drawn for accurate dose selection, which may

aid in patients with low vision.38

Medication Errors

Similar brand names

and packaging of some insulin formulations can cause confusion and lead to

medication errors.39 Verbal insulin orders should be confirmed with

a written prescription whenever possible. With written orders, the practice of

using the letter "u" to indicate units must be strongly discouraged, since it

can be misread as the number four or a zero, increasing the insulin dose

10-fold. The pharmacy could also recommend "tall-man nomenclature" to avoid

confusion between preparations with similar-sounding names, for example,

NovoLIN 70/30 and NovoLOG Mix 70/30.39

New Additions to the Diabetes

Armamentarium

Pramlintide (Symlin), an injectable synthetic analog of the pancreatic enzyme

amylin given twice daily in type 2 diabetes, can be used in insulin-treated

patients to reduce PPG.16 Exenatide (Byetta), an incretin mimetic

given subcutaneously twice daily, stimulates insulin secretion in a

glucose-dependent manner to lower PPG and has glycemic efficacy similar to

oral agents; it also promotes significant weight loss.40 A DPP-4

inhibitor that degrades incretins, sitagliptin (Januvia), has been approved,

and a second addition to this class, vildagliptin (Galvus), may be approved in

the future for oral administration in type 2 diabetes.40

Role of the Pharmacist

Pharmacists are uniquely placed to provide education and diabetes management

services, and many have implemented education- or diabetes-related sections in

the pharmacy. Training to become a certified diabetes educator can further

solidify and expand the pharmacist's role in diabetes care, especially through

collaboration with other health care professionals. Diabetes medication

management, sick-day guidelines, SMBG, American Diabetes

Association–recommended treatment goals, and basic information in all aspects

of diabetes self-management care can potentially be taught by pharmacists.

Conclusion

In order to prevent or delay the onset of diabetes-specific complications, the

glycemic goal in the management of type 2 diabetes is to achieve near-normal

HbA1c levels without hypoglycemia. Because type 2 diabetes is a progressive

disease, multiple agents, including insulin, may be required to achieve

targeted glycemic goals. Proper choice of the insulin regimen, based on

patient factors, can increase the chances of successful implementation.

Insulin analogs may help to achieve these goals by easily allowing patients to

fit the insulin regimen into their lifestyles. Newer delivery devices and

novel routes of administration may offer greater ease of use and precision in

the dosing of insulin. The pharmacist, as a trusted source of drug

information, should play a vital role in the care of patients with type 2

diabetes using insulin.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control. National diabetes fact sheet. United States, 2005: general information. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/pdf/ndfs_2005.pdf. Accessed March 30, 2007.

2. United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet. 1998;352:837-853.

3. UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Effect of intensive blood-glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34). Lancet. 1998;352:854-865.

4. Stratton IM, Adler AI, et al. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ. 2000;321:405-412.

5. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes--2007. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(suppl 1):S4-S41.

6. Weir GC, Bonner-Weir S. Five stages of evolving beta-cell dysfunction during progression to diabetes. Diabetes. 2004;53(suppl 3):S16-S21.

7. DeFronzo RA. Pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Med Clin North Am. 2004;88:787-835.

8. Monnier L, Colette C, et al. Contributions of fasting and postprandial glucose to hemoglobin A1c. Endocr Pract. 2006;12

(suppl 1):42-46.

9. Hirsch IB, Bergenstal RM, et al. A real-world approach to insulin therapy in primary care practice. Clin Diabetes. 2005;23:78-86.

10. Alvarsson M, Sundkvist G, et al. Beneficial effects of insulin versus sulphonylurea on insulin secretion and metabolic control in recently diagnosed type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2231-2237.

11. Royal College of Nursing. Starting insulin treatment in adults with type 2 diabetes. Available at: www.library.nhs.uk/guidelinesfinder/ViewResource.aspx?resID=57582. Accessed March 30, 2007.

12. Meece J. Dispelling myths and removing barriers about insulin in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2006;32:9S-18S.

13. Rolla AR, Rakel RE. Practical approaches to insulin therapy for type 2 diabetes mellitus with premixed insulin analogues.

Clin Ther. 2005;27:1113-1125.

14. Mayfield JA, White RD. Insulin therapy for type 2 diabetes: rescue, augmentation, and replacement of beta-cell function. Am Fam Physician. 2004;70:489-500.

15. Dailey G. A timely transition to insulin: Identifying type 2 diabetes patients failing oral therapy. Formulary. 2005;40:114-130.

16. Nathan DM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a consensus algorithm for the initiation and adjustment of therapy. A consensus statement from the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1963-1972.

17. Lilley SH, Levine GI. Management of hospitalized patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am Fam Physician. 1998;57:

1079-1088.

18. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Antidiabetic agents. In: American Hospital Formulary Service Drug Information. Bethesda, MD: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists; 2006:3072-3149.

19. Triplitt CL, Reasner CA, Isley WL. Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach. 6th ed. New York: McGraw Hill; 2005:1345.

20. Mandal TK. Inhaled insulin for diabetes mellitus. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2005;62:1359-1364.

21. Davidson MB, Mehta AE, Siraj ES. Inhaled human insulin: an inspiration for patients with diabetes mellitus? Cleve Clin J Med. 2006;73:569-578.

22. Riddle MC. Glycemic management of type 2 diabetes: an emerging strategy with oral agents, insulins, and combinations. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2005;34:77-98.

23. Hermansen K, Davies M, et al. A 26-week, randomized, parallel, treat-to-target trial comparing insulin detemir with NPH insulin as add-on therapy to oral glucose-lowering drugs in insulin-naive people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1269-1274.

24. Hirsch IB. Insulin analogues. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:

174-183.

25. Brunton S, Carmichael B, et al. Type 2 diabetes: the role of insulin. J Fam Pract. 2005;54(suppl 5):445-451.

26. Rave K, Bott S, et al. Time-action profile of inhaled insulin in comparison with subcutaneously injected insulin lispro and regular human insulin. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1077-1082.

27. Riddle MC, Rosenstock J, Gerich J. The treat-to-target trial: randomized addition of glargine or human NPH insulin to oral therapy of type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:

3080-3086.

28. Siebenhofer A, Plank J, et al. Short acting insulin analogues versus regular human insulin in patients with diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004; CD003287.

29. Jellinger PS, Davidson JA, Blonde L, et al. Road maps to achieve glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus: ACE/AACE Diabetes Road Map Task Force. Endocr Pract. 2007;13:260-268.

30. Texas Department of State Health Services. Insulin algorithm for type 2 diabetes mellitus in children and adults. Publication #45-11647. Available at: http://www.dshs.state.tx.us/diabetes/PDF/algorithms/INST2.pdf. Accessed March 30, 2007.

31. Raskin P. Can glycemic targets be achieved--in particular with two daily injections of a mix of intermediate- and short-acting insulin? Endocr Pract. 2006;12(suppl 1):52-54.

32. Yki-Jarvinen H. Combination therapies with insulin in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(4):758-767.

33. Rosenstock J, Davies M, et al. Insulin detemir added to oral anti-diabetic drugs in type 2 diabetes provides glycemic control comparable to insulin glargine with less weight gain. Diabetes. 2006;55(suppl 1)A132. Abstract.

34. Malone JK, Bai S, et al. Twice-daily pre-mixed insulin rather than basal insulin therapy alone results in better overall glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2005;22:374-381.

35. Raskin P, Allen E, et al. Initiating insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes: a comparison of biphasic and basal insulin analogs.

Diabetes Care. 2005;28:260-265.

36. Garber AJ, Wahlen J, et al. Attainment of glycaemic goals in type 2 diabetes with once-, twice-, or thrice-daily dosing with biphasic insulin aspart 70/30 (the 1-2-3 study). Diabetes Obes Metab. 2006;8:58-66.

37. Liebl A, Prager R, et al. Biphasic insulin aspart 30 (BIAsp30), insulin detemir (IDet) and insulin aspart (IAsp) allow patients with type 2 diabetes to reach A1C target: the PREFER study. Diabetes. 2006;55(suppl 1)A123. Abstract.

38. Asakura T, Seino H. Assessment of dose selection attributes with audible notification in insulin pen devices. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2005;7:620-626.

39. Paparella S. Avoiding errors with insulin therapy. J Emerg Nurs. 2006;32:325-328.

40. Triplitt C, Wright A, Chiquette

E. Incretin mimetics and dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibitors: potential new

therapies for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Pharmacotherapy.

2006;26:360-374.

To comment on this article, contact editor@uspharmacist.com.