US Pharm.

2006;7:28-34.

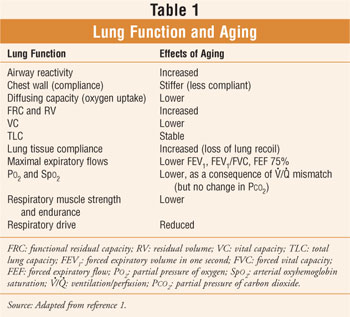

Age impacts lung function. It is an undisputed fact that changes in lung function occur with aging in healthy, nonsmoking individuals (Table 1).1 If an individual smokes, the situation is compounded and havoc can strike. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the most common chronic respiratory disease among seniors. In addition, COPD morbidity and mortality are on the rise.1,2

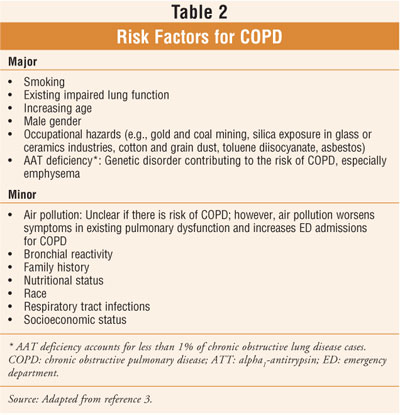

Although there are numerous risk factors associated with COPD (Table 2), the disease is largely preventable, since its main cause is cigarette smoking. In lifetime nonsmokers in whom exposure to environmental tobacco smoke results in at least some disease, COPD is rare (estimated incidence 5% in three large representative U.S. surveys from 1971 to 1984).3-5 In fact, smoking accounts for approximately 85% of COPD mortality in men and 69% of COPD mortality in women.6

A national report published in 2000

notes that 14% of all hospital admissions of elderly individuals are due to

respiratory disease.7 According to 1995 mortality statistics, COPD

and associated conditions accounted for 5% of all deaths in people 65 years

and older.8 In the U.S., estimated prevalence of COPD has risen by

41% since 1982.9 In 2003, 10.7 million adults in the U.S. were

estimated to have COPD.10 It should be noted that the terms chronic

obstructive lung disease and chronic obstructive airway disease are synonymous

with COPD.

Characterized by a progressive airflow

limitation, COPD is caused by an abnormal inflammatory reaction to the chronic

inhalation of particles, of which those from cigarette smoke are most

prevalent.3,11 For patients who continue to smoke, airway

obstruction is usually progressive, resulting in early disability and

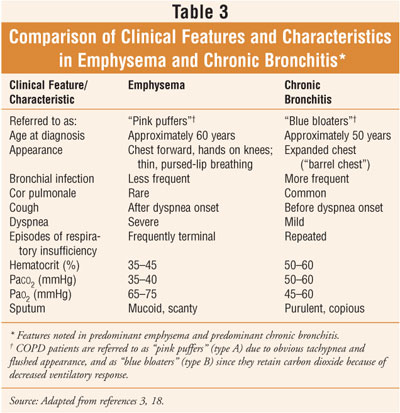

shortened survival.9 The subsets of COPD are chronic bronchitis and

emphysema; while their pathology and clinical characteristics differ (table

3), most individuals with COPD show characteristics of both.3

Pathophysiology and Presentation

Chronic bronchitis is defined in

clinical terms as chronic cough or mucus production for at least three months

in at least two successive years when other causes of chronic cough have been

excluded.3,6 Emphysema is defined in terms of anatomic pathology

and is described as an abnormal permanent enlargement of the air spaces distal

to the terminal bronchioles, accompanied by destruction of their walls

(without obvious fibrosis).1 The destruction takes place within the

acinus, the unit of the lung responsible for gas exchange. Patients with

emphysema have a decreased number of capillaries in the walls of the alveoli.

Fewer blood vessels and airway obstruction causes impaired movement of oxygen

and carbon dioxide between the alveoli and the blood.12

Patients who present with predominant

emphysema tend to be older than those who present with predominant chronic

bronchitis (table 3). Patients with COPD may have symptoms associated with a

severely low blood oxygen level, including shortness of breath, pulmonary

hypertension, right-sided heart failure, and polycythemia (an increase in the

total red blood cell

mass of the blood).12 If the hematocrit is more than 55% to 60%,

acute phlebotomy may be indicated.3 To maintain a lower hematocrit,

long-term oxygen may be necessary.3

Diagnosis and Prognosis

The diagnosis of emphysema is based

on medical history, physical exam, and pulmonary function tests. Chronic

bronchitis is diagnosed solely by a history of a persistent, sputum-producing

cough.12 Due to the high prevalence of comorbidity, the

differential diagnosis of COPD and asthma in the elderly is frequently more

difficult than in younger patients.1 As compared to middle-aged

adults, elderly patients are more likely to have COPD and cardiovascular

disease, both of which are often associated with cigarette smoking and have

symptomatology mimicking asthma.1 Objective pulmonary function (PF)

tests, therefore, have great value in the elderly population.1

In general, as airway

obstruction increases, the prognosis of a patient with COPD worsens, with an

increased risk of death.12 A steeper decline in PF is correlated

with a greater number of years spent smoking and a greater number of

cigarettes smoked.13 The prognosis is considered poor when there is

a rapid decline in PF tests.3 A reduced survival rate is seen in

individuals living in high altitudes.3

Treatment

The treatment for COPD is

palliative, not curative.2 It is probable that longevity cannot be

significantly improved with any treatment, except in patients with hypoxemia

who benefit from supplemental oxygen therapy.2

Smoking

Cessation: Smoking

cessation, including cigarettes, cigars, and pipes, is the most important step

in the treatment of COPD, since smoking is the most common cause.3,12

Smoking cessation can revert the decline in lung function to values of

nonsmokers.14 In fact, an aggressive smoking intervention program

has been shown to significantly reduce the age-related decline in FEV1

in middle-aged smokers with mild airway obstruction.14 Continuation

of smoking essentially ensures that symptoms will worsen.12 Pharmacists

have a huge opportunity for counseling in the smoking cessation arena with

prescription and OTC medication intervention and patient education.

Pharmacologic

Interventions: Medication

intervention usually consists of life-long chronic therapy with dosage

adjustments and additional agents when exacerbations present. According to the

American Lung Association, bronchodilators (oral or inhaled) are central to

the symptomatic management of COPD. Additional treatment includes antibiotics,

oxygen therapy, and systemic glucocorticosteroids.15 Inhaled

glucocorticosteroids continue to be studied.

Chronic systemic steroid

treatment poses the risk of serious side effects and is therefore usually

reserved for acute exacerbations. Patients with COPD should receive pneumonia

and influenza vaccines. Lung transplantation or lung volume reduction surgery

may be an option for certain individuals. In addition, treatments for alpha-1

antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency emphysema, including AAT replacement therapy (a

life-long process) and gene therapy, are being evaluated. For more information

on pharmacologic treatment guidelines for COPD, the reader is referred to the

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease guidelines at:

www.goldcopd.com.

Pulmonary Rehabilitation

A comprehensive pulmonary

rehabilitation (PR) program may lead to significant clinical improvement by

increasing exercise tolerance and reducing shortness of breath.2 PR

programs may even reduce the number of hospitalizations, although to a lesser

extent.2 It should be noted, however, that while PR programs are

aimed at improving independence and improving quality of life, they do not

improve lung function or prolong survival.2,12

Ideally, a variety of health

care professionals are required to deliver the wide range of services offered

in a comprehensive PR program. Educating patients about their disease is a key

component. Exercise training, often with oxygen, may take place at the home or

in a clinic setting and often includes stationary bicycling, stair climbing,

and walking to improve leg strength, plus weight lifting to improve arm

strength.12 Techniques are taught to decrease shortness of breath

during exercise and sexual activity. Additionally, patient evaluation and goal

setting, nutritional evaluation and counseling, psychosocial counseling

(addressing depression, anxiety, sexual activity limitations), and the

coordination of complex medical services (e.g., home visits, medical

equipment, physician visits) are also provided.2 Medication

counseling is an important and integral part of PR, since medication

nonadherence is a serious complicating factor in COPD management.2 Education

regarding the appropriate dosing and timing of regularly scheduled and

as-needed medications, the proper technique for self-administering inhaled

medications, ongoing monitoring, and information for family members and

caregivers is imperative.

End-Stage Disease

Mechanical ventilation may be necessary for short- or long-term use; some individuals may become dependent on a ventilator until death.12 Quality of life is diminished with mechanical ventilation due to the patient's inability to speak or eat during these periods. Therefore, it is important for patients to discuss with their physician and loved ones whether they wish to have this form of therapy. Hospice care is an alternative to mechanical ventilation. Advance care planning should be discussed so that a patient can ensure that his or her wishes are carried out.

Advance Care Directives

Advance care planning, in essence,

involves a competent patient and his or her physician discussing and

documenting the patient's preferences for future medical care. Legal

documents, called advance care directives, help minimize the emotional

confusion and distress associated with making and living with difficult health

care decisions for another individual. Most importantly, they help ensure

adherence to a patient's wishes regarding the manner in which he or she will

die.

There

are two types of advance directives: a living will and a durable power of

attorney.16 The living will is a document that describes a

patient's preferences for the initiation, continuation, or discontinuation of

particular forms of treatment.16 A durable power of attorney is a

document that designates a surrogate (e.g., agent, proxy [as in the term health

care proxy], or attorney-in-fact) who will make medical decisions on behalf of

the patient, should the patient become incapable of doing so.16 It

is important for the patient or the advocate to complete these documents while

the patient is in full command of his or her faculties; thus, the patient's

judgment will not be challenged.17 One may obtain advance directive

forms in a hospital, health care institution, or in the community (e.g.,

senior centers, area agency on aging, attorney's office). Additionally, verbal

statements made by the patient in conversations with physicians, family, and

friends are recognized ethically--and in some states legally--as advance

directives, as long as they are appropriately charted in the medical record.16

"Do-Not-Resuscitate" Orders

The Do-Not-Resuscitate (DNR) order is a statement indicating that cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) will not be performed in the case of cardiopulmonary arrest. However, DNR orders do not mean do not treat. Other treatments, including ventilatory support, transfusions, dialysis, and antibiotics, may be given. Most hospitals and nursing homes have policies to help guide families in the decision-making process regarding resuscitation, and most require that the subject be discussed with the patient and the family. The possibility of CPR and a description of CPR procedures should be discussed with the physician. A patient's preferences regarding interventions should be elicited early during a hospitalization or while the patient is still in an outpatient setting.17 Legal experts recommend avoiding nonspecific terms such as heroic measures or extraordinary treatments.

Conclusion

The most common cause of COPD is cigarette smoking; the most important step in its treatment is smoking cessation. For COPD patients who continue to smoke, airway obstruction is usually progressive, resulting in early disability and shortened survival. All COPD patients, including the elderly, require tailored medication regimens and medication counseling and should be considered for a PR program aimed at improving independence and quality of life. Many clinicians may have difficulty accepting a patient's choice to decline aggressive care and accept impending death. Therefore, patients should discuss their decisions with physicians, family members, and caregivers, and they should prepare advance care directives that articulate their preferences regarding future health care interventions.

REFERENCES

2.

Beers MH, Berkow R, eds. The Merck Manual of Geriatrics. 3rd ed.

3.

Konzem SL, Stratton MA. Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. In: DiPiro JT,

Talbert RL, Yee GC, et al, eds. Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach.

5th ed.

4.

Whittemore AS, Perlin SA, DiCiccio Y. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in

lifelong nonsmokers: results from NHANES. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:702-706.

5.

Brunekreef B, Fischer P, Remijn B, et al. Indoor air pollution and its effect

on pulmonary function of adult non-smoking women: III. Passive smoking and

pulmonary function. Int J Epidemiol. 1985;14:227-230.

6.

American Thoracic Society. Standard for the diagnosis and care of patients

with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med.

1995;152:S77-S120.

7.

8.

Anderson RN, Kochanek KD, Murphy SL. Report of final mortality statistics,

1995. Monthly Vitality Statistics Report. 1997;45(Suppl 2): table 7.

9.

Barton S, Jones G, Gabriel L, et al, eds. Clinical Evidence: Consultant

Pharmacist Edition.

10.

11.

Pauwels RA. National and international guidelines for COPD: The need for

evidence. Chest. 2000;117:20S-22S.

12. Beers MH, Jones TV, Berkwits M,

et al, eds. The Merck Manual of Health & Aging.

13.

Celli BR. The importance of spirometry in COPD and asthma. Chest.

2000;117:15S-19S.

14.

Anthonisen NR, Connett JE, Kiley JP, et al. Effects of smoking intervention

and the use of an inhaled anticholinergic bronchodilator on the rate of

decline of FEV1: the lung health study. JAMA. 1994;272:1497-1505.

15.

American Lung Association. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Fact

Sheet. Available at:

www.lungusa.org/site/pp.asp?c=dvLUK9O0E&b=35020&printmode=1 Accessed June 20,

2006.

16.

Karlawish JHT, James BD. Ethical Issues in Geriatric Medicine: Informed

Consent, Surrogate Decision Making, and Advance Care Planning. In: Hazzard WR,

Blass JP, Halter JB, et al. Principles of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology.

5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Inc; 2003:353-360.

17.

Zagaria ME. Legal aspects of eldercare: The living will, healthcare proxy, and

do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order. US Pharmacist. 2002;12:68-69.

18.

Honig EG, Ingram RH. Chronic bronchitis, emphysema, and airways obstruction.

In: Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Isselbacher KJ, et al, eds. Harrison's Textbook of

Internal Medicine. 14th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Inc; 1998:1451-1460.